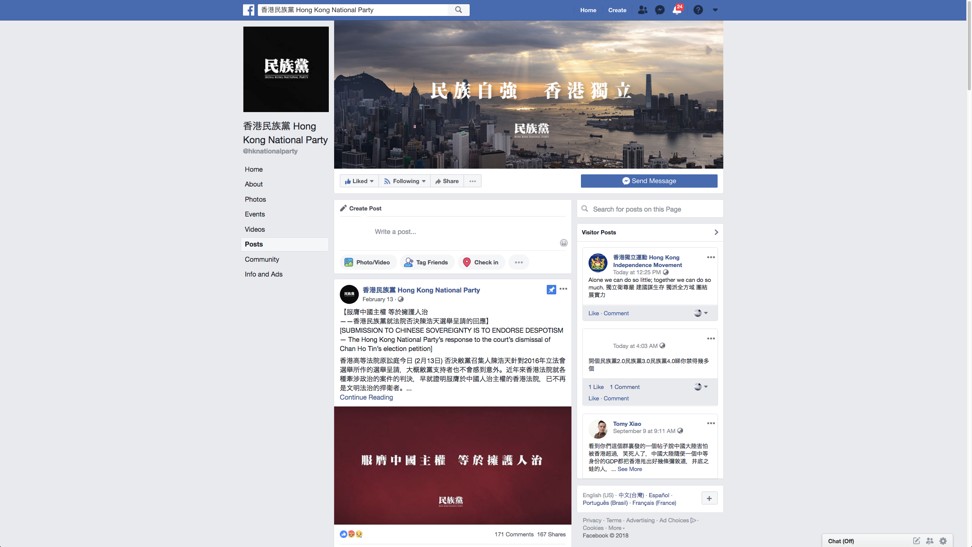

Will Facebook agree to Hong Kong police’s request to take down page of banned Hong Kong National Party?

Following the unprecedented ban on the separatist party issued on Monday, local police make request to social media giant asking it to remove HKNP page

Facebook is keeping quiet on whether it will agree to Hong Kong police’s request for the social media giant to take down the page of a local separatist party outlawed by the government on Monday.

In explaining the ban, Hong Kong Security Minister John Lee Ka-chiu said on Monday it was on grounds of national security, public safety, public order and the protection of the rights and freedoms of others. He also warned that anyone who associates with the party by serving the group, participating in gatherings, providing financial assistance or aid could be liable on conviction to a fine and jail sentence of two to three years.

Aid could be broadly defined as providing a platform for the banned party to promote its operations, as legal scholars had suggested, which means Facebook could face possible criminal liability should the HKNP publish new posts on the platform to promote its causes.

A senior government source said the police on Monday had asked Facebook to take down HKNP’s page after the government declared the party illegal, but the social media giant had not yet responded to the request.

If it doesn’t violate their policies, then [Facebook] would assess it against Hong Kong law. If they agree it violates Hong Kong law, the removal would be for Hong Kong only

“The force will monitor if there are any updates on the party’s page. It is too early to comment if any new post means a breach of law,” the source said.

The Post understands that the force has neither made similar requests to other social media companies, nor demanded the HKNP’s official website, which was no longer functioning on Tuesday, to be taken down.

When contacted, a Facebook spokeswoman said it had no comment. The party’s page remained intact as of Tuesday evening.

Dr Lokman Tsui, an assistant professor at the Chinese University’s journalism school, said that from what he understood, the social media giant would first check if the HKNP page had violated its own policies and terms of services, such as whether it involved any content promoting terrorism. If it is internally agreed there was a violation, he said, Facebook would take down the page globally.

“If it doesn’t violate their policies, then they would assess it against Hong Kong law. If they agree it violates Hong Kong law, the removal would be for Hong Kong only,” Tsui said.

It would not be the first time the social media giant has had to grapple with such situations.

In 2015, Facebook was accused by Sikhs for Justice (SFJ), a human rights group advocating for Sikh independence in the Indian state of Punjab, of blocking its page because of its call to hold a separatist referendum. SFJ alleged the move was made at the Indian government’s behest.

A threat to city’s freedom or a necessary step for security? Hong Kong National Party ban divides opinion

The community standards of Facebook have also stated hate speech is not allowed on the platform because “it creates an environment of intimidation and exclusion and in some cases may promote real-world violence”.

In March, it removed the pages of Britain First – an anti-Islamic group – and its leaders on grounds that they had repeatedly violated its community standards by inciting hatred against Muslims.

The ban was welcomed by Prime Minister Theresa May and London’s mayor, Sadiq Khan.

Hong Kong’s security minister, Lee, on Monday had cited the HKNP’s attempt to spread hatred and discrimination against mainlanders in Hong Kong as one of the reasons which justified the ban, as that had affected the rights and freedoms of others.

Pro-democracy lawmaker Charles Mok, representing the information technology sector in the legislature, said it was not unusual for police to request a takedown of webpages violating certain criminal laws, but it was a common practice for them to request a court warrant before the internet service provider would take action.

He also feared the development would harm the city’s business image, which has long emphasised the free flow of information.

“Facebook might have faced similar situation in other countries such as Venezuela or Myanmar where political factors have played a role in the countries’ free flow of information, but not Hong Kong before,” he said.

“The development would hurt the city’s business reputation … and is very dangerous considering the current global climate under trade war.”