Chung Sze-yuen, the voice of Hongkongers in the British colonial corridors of power, leaves a political legacy few can match

- The former Executive Council convenor died on Wednesday aged 101

- He went from engineering to education to the highest echelons of politics, where he eventually found ‘his life and the destiny of Hong Kong were forever fused’

Chung Sze-yuen leaves a legacy few in Hong Kong can match.

As the only Hongkonger to play an active part in negotiations for the handover of sovereignty from Britain to China, it was Chung’s encounter with paramount leader Deng Xiaoping in Beijing that was widely seen as the defining moment of a Chinese representative inside the colonial corridors of power.

Chung, who died on Wednesday aged 101, told Deng frankly Hongkongers lacked confidence in the city’s future.

“People are worried that instead of genuinely being administered by the people of Hong Kong, the future government of the special administrative region would actually be governed from Beijing,” Chung said at a meeting in the Sichuan Room of the Great Hall of the People on June 23, 1984.

Deng had pledged to allow Hong Kong people to rule the city after 1997 under the “one country, two systems” formula.

He also told Deng, who did not recognise Chung’s status as an Executive Councillor, that the middle- and lower-ranking cadres responsible for implementing China’s policy over Hong Kong might not be able to accept the capitalist systems and lifestyle of the city.

While the people of Hong Kong had faith in Deng, Chung said, they were concerned the future policy of China might change and future leaders might revert to extreme left policies.

With a spittoon by his side, Deng had only a blunt reply to Chung’s remarks.

“Actually that is your opinion. It is you who have no faith in the People’s Republic of China,” Deng told Chung.

Chung was later lambasted by Xu Jiatun, then director of the Hong Kong branch of state news agency Xinhua, which also acted as a de facto embassy for Beijing. Xu called Chung a “mandarin of the departing colonial regime”.

Chung, who was Senior Member of the Executive Council – the top policymaking body in the colonial era – had travelled to Beijing with his fellow Exco colleagues Lee Quo-wei and Lydia Dunn.

After their meeting with Deng, the trio proposed to senior mainland Chinese officials that Beijing should form a Basic Law Legal Committee comprising Chinese people of international standing and reputation to advise on the drafting and implementation of the Basic Law. The idea was similar to the Basic Law Committee which was eventually adopted in the Basic Law.

A month after his trip, Chung proposed a referendum in Hong Kong to test the acceptability of the Joint Declaration – that agreed the terms of the handover – but the idea was rejected by then governor Edward Youde, who said turnout would be low.

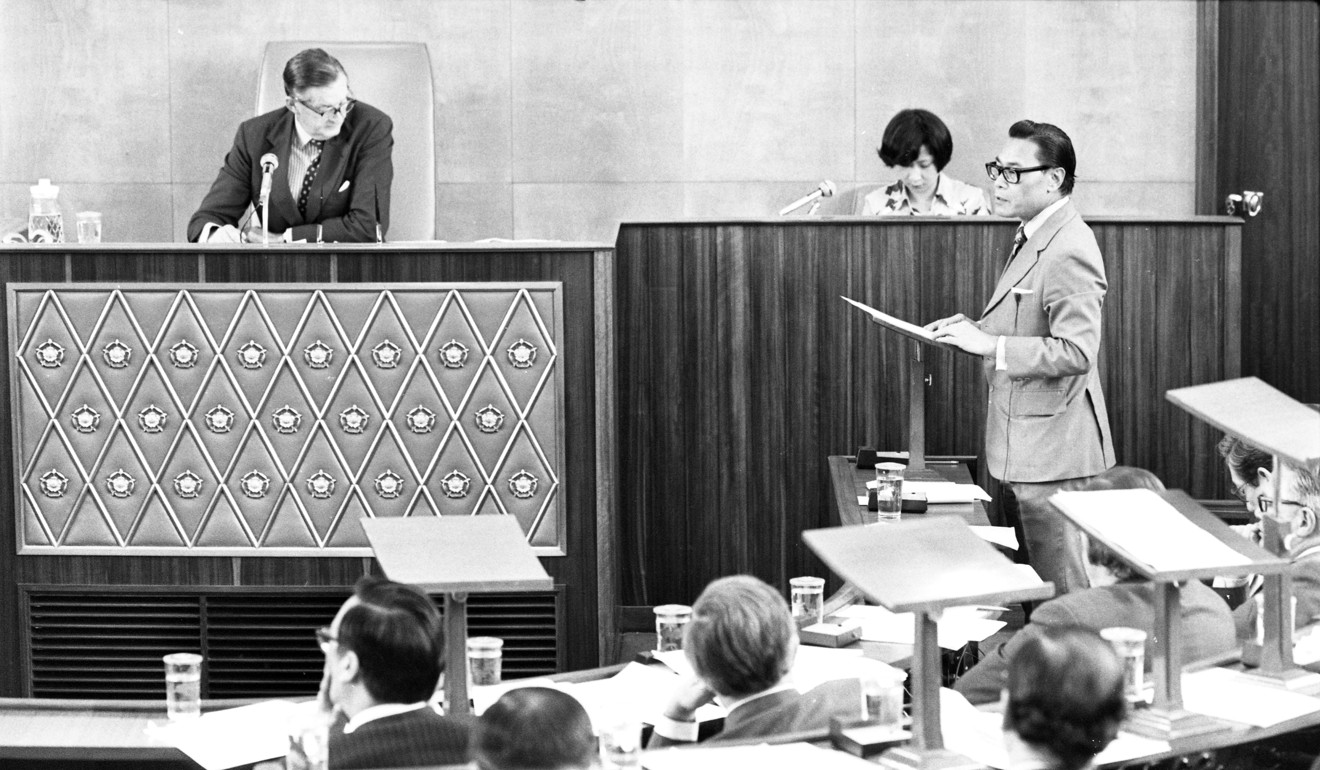

After becoming Senior Member of the Executive Council in 1980, Chung quickly became an integral part of Sino-British wrangling.

Former Hong Kong Executive Council convenor Chung Sze-yuen, ‘godfather of local politics’, dies aged 101

“From the moment I accepted the challenge, my life and the destiny of Hong Kong were forever fused,” Chung said in his 2001 memoir, H ong Kong’s Journey to Reunification.

The episode was “the most difficult in my political life”, Chung later said, as he felt he was distrusted by both Chinese and British side.

“A few [Exco members] strived to join the negotiating table but our requests were not accepted – the British government found me annoying,” Chung said.

And Chinese officials felt the Exco members were siding with the colonial government.

As far back as 1965, Chung was already a legislator and he was named a senior member of the Legislative Council in 1974.

Hong Kong’s elite gather to mark 101st birthday of ‘godfather’ of politics

In 1972, then governor Murray MacLehose promoted Chung to Exco, where he retained key positions under two subsequent governors, Youde and David Wilson.

Chung was no stranger to innovative, if not controversial, proposals to break the ice between Hong Kong and mainland China even before his trip to Beijing in 1984.

According to declassified British archives, Chung in 1980 raised the idea of building an airport on the Chinese side of the border, in the hope of fostering closer ties with Beijing. He suggested it could be jointly used by Hong Kong and mainland China and also proposed the Hong Kong government foot the bill for construction.

The British government was not interested.

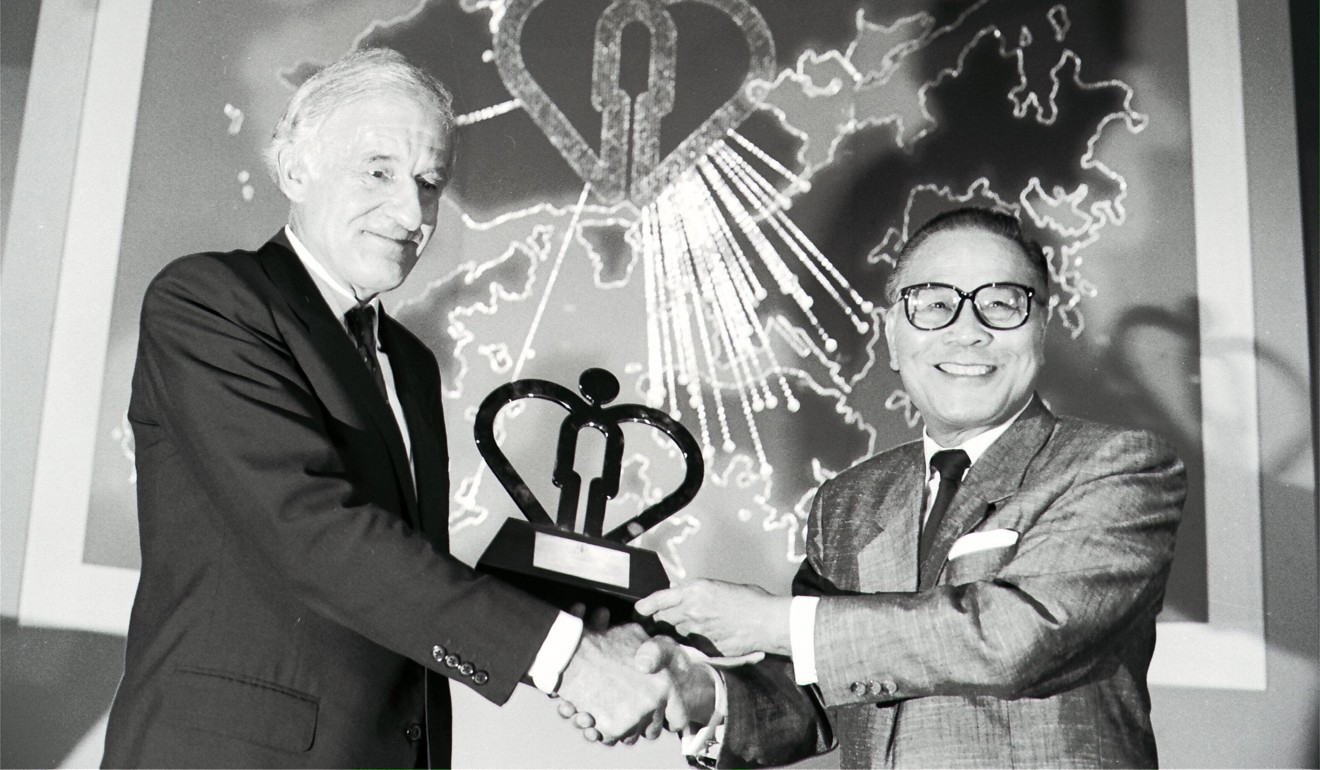

Chung retired from Exco in 1988 and in 1990 became founding chairman of the Hospital Authority which managed Hong Kong’s public hospitals. He staged an unexpected political comeback in 1997, when he became the city’s first Exco convenor after the handover under then Hong Kong chief executive Tung Chee-hwa.

Chung obtained a mechanical engineering doctorate in 1951 from the University of Sheffield.

After graduation, he set up torch manufacturer Sonca and registered a patent in 1967.

From war camps to Occupy: how South China Morning Post covered Hong Kong history

But it was the textile business that would bring him into four decades of public service, he later said.

In his memoir, he recalled how Hong Kong’s textile trade flourished in the 1950s and made inroads into the global market, worrying British and American manufacturers. Swayed by domestic pressures, the British government imposed restrictions on imports from its Chinese colony.

The industry in the city was at the time unorganised and efforts to lobby London against the decision were unsuccessful.

Then governor Alexander Grantham decided there should be a trade association to unite their voices. Chung would lead the charge in 1958 under subsequent governor Robert Black, who asked him and another senior Exco member, Chau Sik-nin, to set up the organisation.

The body became the Federation of Hong Kong Industries and Chung became the federation’s second chairman in 1966, but a major riot in Hong Kong the following year would cause him to rethink his political approach.

Hong Kong press freedom is becoming history, like the days of its being a British colony

“Chau and I were nervous, so we formed a group with a few friends from the business sector and discussed Hong Kong’s political future.”

He was also well connected in the business world. He joined the board of Sun Hung Kai Properties in 2001 and stayed until 2009.

Chung also became a staunch supporter of Henry Tang Ying-yen when Tang ran for chief executive in 2012. At a rally in December 2011 in support of Tang’s bid for the city’s top job, Chung said: “I am 95 and came here with a walking frame. I come to tell you that I sincerely support Henry Tang.”

Chung placed the wrong bet, with Tang eventually losing to Leung Chun-ying.

But Chung had also earlier been a supporter of Leung. When the future leader succeeded him as Exco convenor in 1999, Chung dismissed the concerns of critics who said Leung, then 44, was too young for the job.

“Bill Clinton became US president when he was just 40-odd years old,” Chung said.