Declassified files reveal disagreement between Chris Patten and British government over how to deal with China before Hong Kong handover in 1997

- Governor Chris Patten was at odds with country’s own diplomats when it came to negotiating tactics

- Patten’s electoral reform proposals angered Beijing, and 1993 talks ultimately collapsed

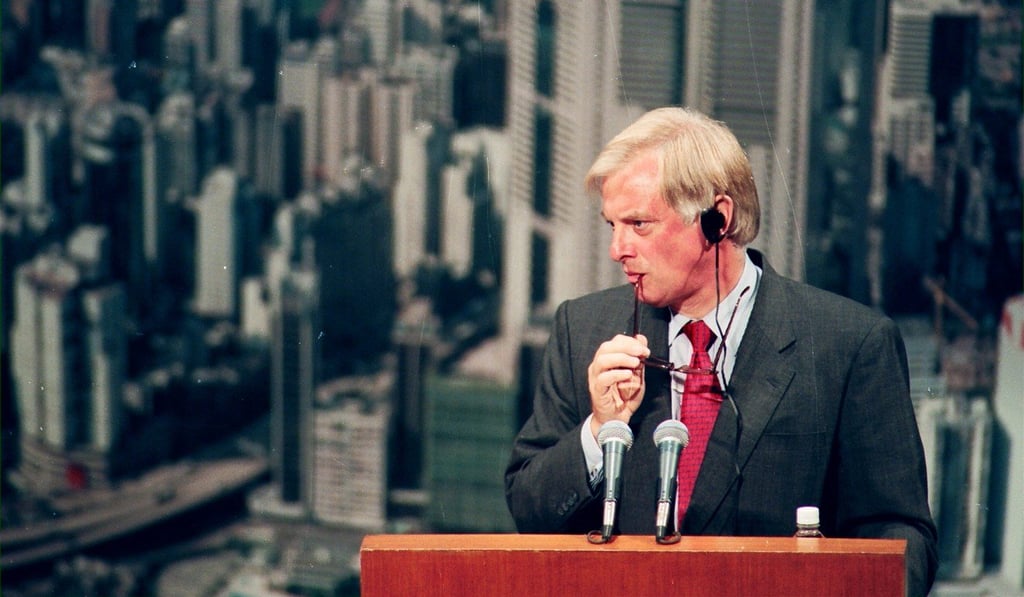

The city’s last governor, Chris Patten, squabbled with British negotiators over their tactics in talks with Beijing on electoral reform in Hong Kong’s before the 1997 handover, newly declassified British files reveal.

Patten’s proposal to give 2.7 million residents the vote angered China, and put him at odds with some of his country’s own diplomats, who took a more pragmatic approach.

Files released by the National Archives in London last week have revealed the internal discussions within the British government on how to deal with negotiations in 1993.

In a telegram to assistant undersecretary for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs Christopher Hum on February 15, 1993, Robin McLaren, Britain’s top negotiator, suggested taking the initiative to move the talks forward to more substantive discussion, by exploring Beijing’s reactions to possible alternatives.

“To get to the next stage of substantive discussion, we should have to take the initiative. Whether this happened over the main negotiation table, in restricted session or in some even more private format we should have to explore Chinese reactions to some possible alternatives,” wrote McLaren, who was also Britain’s ambassador to China at the time.