Extradition bill crisis: how the Hong Kong government had the ‘perfect’ listening mechanisms, but turned a deaf ear to public sentiment

- In a new series of in-depth articles on the unrest rocking Hong Kong, the Post goes behind the headlines to look at the underlying issues, current state of affairs, and where it is all heading

- We examine how Carrie Lam’s administration failed to gauge the popular mood before launching the bill, and what that implies for the way it governs

Ever since he was a young district councillor pounding the pavements of the working-class neighbourhood of Sham Shui Po, Tam Kwok-kiu knew keeping his ear to the ground was vital if he was to be of any use to his constituents.

Whenever there was a major policy to be passed, he and other councillors would be asked for their assessment of how ordinary Hongkongers would view them. Whether it was a policy on retirement protection or the electoral reforms of the 1990s and the 2000s, he and other councillors would be right in the thick of consultations. They aired their residents’ concerns openly and candidly, feeling they had a stake in the city’s future.

But when the government announced in February it was amending the law to allow for ad hoc extradition to countries with which Hong Kong did not have a deal in place, Tam was left out of the conversation.

“They did not table the bill for discussion at Sham Shui Po District Council at all,” the 62-year-old said. “It was incomprehensible to me that the government did not bother to listen to our views on such a crucial issue.”

Tam was not the only one. Councillors from the other 17 district councils similarly did not learn the news from the government. They got wind of it like everyone else – from the media.

As Hong Kong continues to seethe two months after mass protests erupted over the extradition bill and with no resolution in sight, one oft-heard lament of Hongkongers is how their grievances with a government that was deaf to them have built up over the years. The dam of pent-up discontent finally burst with the extradition bill.

Government insiders have claimed to be stunned by the depth of anger. But the greater surprise is that, on paper at least, the Hong Kong government is actually equipped with a near-perfect machinery to take the political pulse of the populace. Officials in charge of district administration are supposed to maintain contact with members of the public through 18 district councils, 63 area committees, 1,702 mutual aid committees and 10,771 owners’ corporations, all of which serve as links between the government and local community.

Apart from the network of district administration across the city, about 5,600 members of the public from all walks of life serve on about 490 advisory and statutory bodies which tap professional expertise in the community and allow input in the initial stage of policymaking.

Two months on, what do Hong Kong protesters really want

With so many layers of institutions and feedback mechanisms, why didn’t the “alarm systems” at various levels send out alerts to the top echelons of the government?

As analysts study the runes of a government now in retreat, it would appear that the roots of the crisis lie in this overwhelming feeling among Hong Kong people they were not being heard. Call it the Great Disconnect between the governed and the government. How it can ever be repaired – or even if it might be at all – will be a key question for any reconciliation in the city to happen.

How the feedback mechanism worked in colonial era

Veteran politicians and academics suggest one starting point might be to study the history of the colonial government’s efforts to canvass public opinion before Hong Kong returned to Chinese rule in 1997.

As with the current administration, it took a crisis to jolt the colonial government into introducing reforms. In 1968, it set up a city district officer scheme under which district offices were to maintain contact with local organisations, field complaints and assess the impact of government policies. It was its answer to bridge the gap between the administration and the people that was exposed by the 1966 Star Ferry riots.

In April that year, a 5 cent increase in the fare of the cross-harbour ferry service between Tsim Sha Tsui and Central sparked four days of mayhem, as mobs pelted riot police with stones, looted shops and set fire to buses and public facilities, including fire stations. One person died and 26 were injured in the violence.

One of the duties of district officers was to gather intelligence on public opinion at the grass roots for decision-makers in the government. They had to submit a report on their district, titled “The Anatomy”, within six months of their appointment. Then, they filed weekly reports, based on intelligence gathered on the ground, to the secretary in charge of district administration.

“The report touched on bread-and-butter issues affecting the district, such as fare increases on public transport,” a former district officer in the 1980s said.

“The secretary in charge of district administration then compiled a report based on the information provided by district officers and submitted it for discussion at a meeting chaired by the governor every Friday,” he said. “The mechanism of gathering intelligence at district level was designed to perform the function of political parties which had not emerged at the time. It worked quite effectively at that time.”

Opinion: Is there a place in Hong Kong for its creative, thoughtful protesters?

In the absence of democratic elections for the Legislative Council, the district officer scheme was a crucial component of the “government by consultation” vaunted by the colonial administration. In 1982, the government introduced the district board system and the first election was held that year. Functional constituencies – with electorates drawn from various trade and professional sectors – were introduced in 1985. Direct elections for Legco arrived in 1991.

Despite such direct engagement with the people, the government retained the district officer system after the handover and officers are to this day required to submit a weekly report – now known as “Community Reactions” – to the Home Affairs Bureau.

Andrew To Kwan-hang, a member of Wong Tai Sin District Council from 1991 to 2011, said the colonial government’s machinery of district administration played a pivotal role in gauging public sentiment at the district level. “Officers and other officials working at district level identified potential problems in the neighbourhood and resolved them before they escalated to a bigger crisis,” he said.

Tam, the Sham Shui Po councillor, said the colonial government spared no effort in understanding public sentiment to make up for its legitimacy deficit.

“The colonial government did not adopt all of our views but they appeared to listen to them sincerely. For example, we fought for the introduction of a central provident fund in the 1990s and the government responded by implementing the Mandatory Provident Fund,” added To, who was chairman of the pro-democracy League of Social Democrats from 2010 to 2011.

Empty shells as feedback mechanism

But if the system inherited from the colonial government is still in place, why did it fail to work this time? Politicians across the board interviewed by the Post lamented that since the turn of the century, the mechanism had not worked as effectively as before.

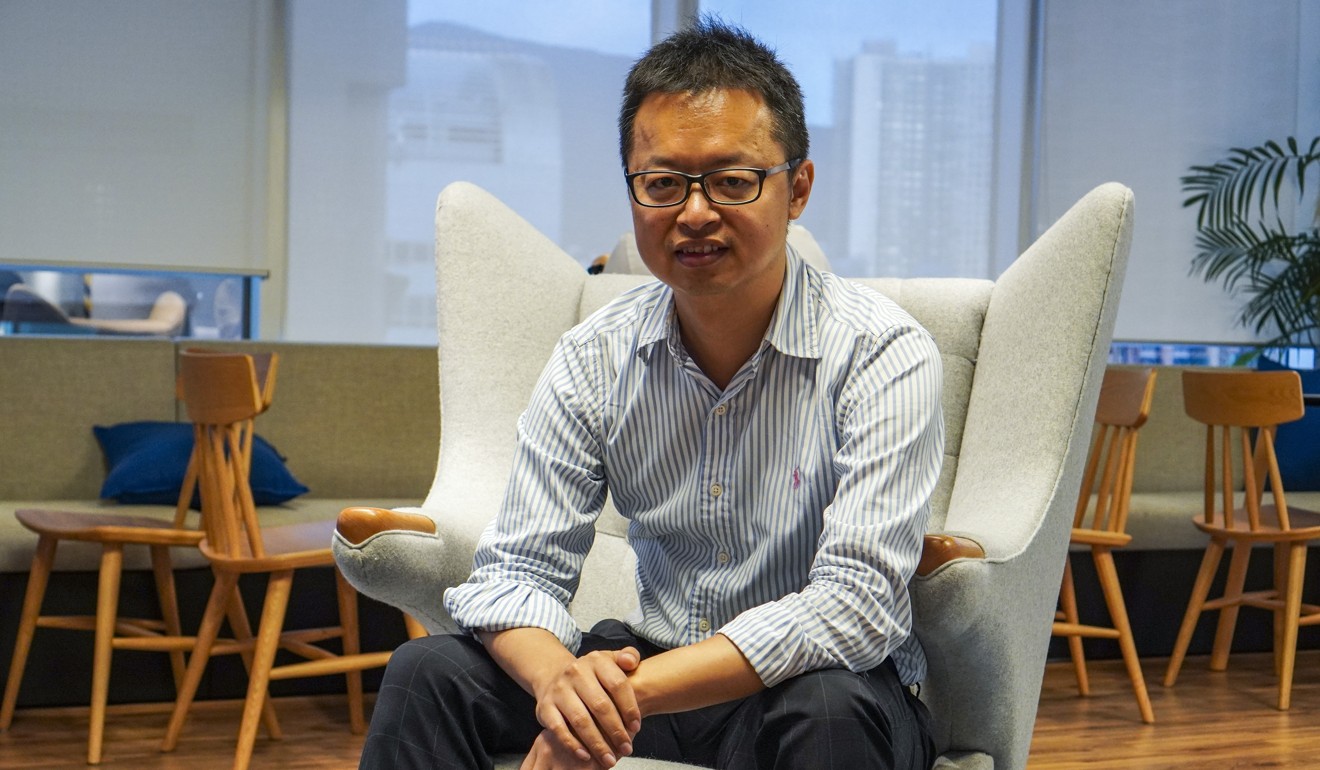

Kin Hung Kam-in, vice-chairman of Kwun Tong District Council, said the process of canvassing public views at district level and the system of advisory committees had atrophied in the past decade.

If officials had the political sensitivity to see that the extradition bill issue might snowball into a big crisis, they would have tabled it for discussion at the meetings of area committees

“If officials had the political sensitivity to see that the extradition bill issue might snowball into a big crisis, they would have tabled it for discussion at the meetings of area committees,” said Hung, a member of the pro-government Democratic Alliance for the Betterment and Progress of Hong Kong (DAB).

“Our members are in close contact with residents. They could have given timely feedback,” he said.

Carrie Lam fights tears to warn protesters against pushing Hong Kong ‘into abyss’

Similarly, the government-appointed area committees also appear to have been neglected. These are intended to provide a link between the local community and the government. Members are mainly headmasters of primary and secondary schools, heads of non-governmental organisations and business organisations in the area.

Until the government decided to suspend the ill-fated bill on June 15, none of the 18 district councils had discussed the bill. Tam, who is also a member of pro-democracy group the Association for Democracy and People’s Livelihood, believed the government deliberately avoided canvassing views of district councils. The reason: to avoid giving media exposure to dissenting voices.

Opinion: Hong Kong, fast forward to 2047

A former district officer said the government was overconfident the bill would be passed easily as the pro-establishment camp holds an overwhelming majority in Legco. “Because of such complacency, the government did not see the need to get a grasp of public sentiment,” the official said.

In Hong Kong politics, 43 pro-establishment lawmakers dominate the 70-member legislature and usually side with the government, even on critical issues.

To deplored the fact the post-handover government kept only the form, and not the substance, of the feedback mechanism. In the end, the government allowed only 20 days for the public to submit their views on the bill.

A source close to the administration said that even before district board elections were held in 1982, officials responsible for district administration spent many hours going door-to-door canvassing opinions in the area.

“It is a puzzle that nowadays, many government-friendly lawmakers and district councillors do not have a good grasp of public sentiment and failed to sound out alerts to senior officials at an earlier stage,” the source said. “It is a question to be answered whether elected representatives have any role to play in the government’s way of listening to the views of members of the public.”

Tam said he had not seen pro-government groups setting up booths on the streets of Sham Shui Po to promote the bill since the government unveiled the proposal to amend the law. “Obviously they didn’t bother to do so and they are now worried about the negative impact on their prospects in district council elections in November,” he said.

Why Hong Kong protesters view police as the enemy

“Many people started to query why the government insisted on pushing the bill through even though Taiwan made it clear it wouldn’t accept Chan’s transfer. Discontent with the government’s handling reached new heights when Carrie Lam insisted on going ahead with the second reading of the bill even after an estimated 1 million Hongkongers marched on June 9,” the official said.

Opinion: Your city needs you: Hong Kong community leaders must step into the breach

To said many pro-government district councillors were content to mingle only with like-minded residents and seldom reached out to those with different views, particularly young people. “They live in their own echo chamber,” he said. Hung from the DAB agreed that, given the growing polarisation in recent years, neither the pro-government nor pan-democratic camps were keen to listen to views they did not subscribe to.

Feedback for validation, not criticism and lack of polling

During Leung Chun-ying’s tenure as chief executive from 2012 to 2017, the government’s think tank the Central Policy Unit (CPU) had a designated team to monitor and analyse online public opinion in blogs, on Facebook and on discussion forums.

The Post understands that the job was taken up by the Information Services Department after the CPU was revamped as the Policy Innovation and Coordination Office (Pico) two years ago under the Lam government. However, the department was not given extra resources for the additional task.

Trudeau extremely concerned about Hong Kong, urges China to be careful

Professor Francis Lee Lap-fung, director of the school of journalism and communication at Chinese University, said the CPU was supposed to be a unit that would not just collect information but also analyse the data and make suggestions. “It is highly questionable whether the Information Services Department can take up the function of doing analysis and making suggestions and how it might do so,” he said.

Lee said the government’s monitoring of online public opinion was also not effective, as the extradition bill controversy embarrassingly showed, raising questions as to whether it had the right people with the skills to track and understand sentiments on social media.

Professor Joseph Chan Man, emeritus professor of journalism and communications at Chinese University, suggested that the government was only willing to listen to public opinion on the internet or from the wider community that was aligned with its own. It preferred validation rather than honest feedback. “This goes beyond the technical issue of how much effort it expends on monitoring online public opinion,” Chan said.

The gap in understanding has not been helped by the absence of regular polling in the past two years. When the Lam government took over in 2017, it remodelled the CPU as Pico and stopped the surveys. The CPU used to conduct regular polls on various topics for top officials.

Could deepening Hong Kong divisions lead to anarchy?

“Nowadays, government officials can only take the public’s pulse by reading news reports and commentaries in newspapers,” the source close to the administration said.

A senior government official said Lam’s administration played down the importance of political work, a major factor in its failure to understand sentiment on the ground. “It abolished the CPU, which gave political advice to top officials, and has not bothered to fill the vacancy of the information coordinator since Lam became chief executive two years ago,” the official said. In the wake of the debacle over the bill, Carrie Lam has now ordered Pico to resume regular polls, the Post has learned.

“Pico is expected to start commissioning surveys on major policy initiatives before the chief executive delivers her third policy address in October,” a government source said.

Advisory committees as echo chambers

While polling and area committees could help the government take the political temperature, the advisory committees were meant for deeper level engagement with people who have expertise to share. But again, like the district councils and area committees, these advisory bodies had over the years morphed into outfits that co-opted like-minded, pro-establishment figures or sidelined those with contrarian views.

A heavyweight in the traditional pro-Beijing camp in Hong Kong who did not wish to be named dismissed the advisory committees as “nothing but empty shells”.

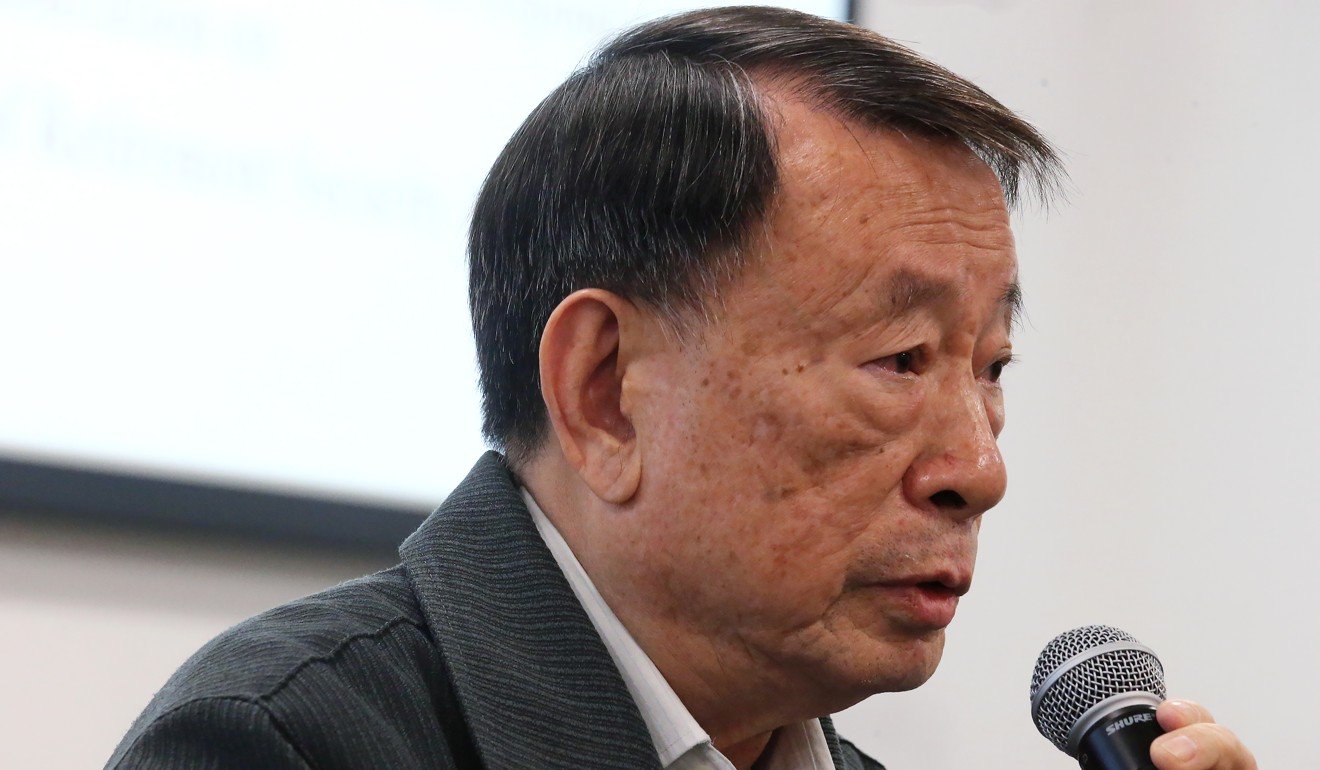

Indeed, even veteran members of these 490 advisory committees and statutory bodies admitted to their waning effectiveness. University of Hong Kong emeritus professor Nelson Chow Wing-sun, who has advised successive governments on welfare issues since the 1980s, said officials often chose to brush aside views that opposed the government’s stance.

Chow, a former chairman of the social welfare advisory committee in the early 1990s, said welfare officials used to consult the committee before rolling out major policy initiatives. “But in recent years, many welfare officials adopt the top-down approach,” he said.

“I think nearly 300 advisory committees could be abolished or their functions should be reviewed as the situation today is different to the time they were established,” he suggested.

Vincent Ng Wing-shun, an architect and a nominator of Lam in the 2017 chief executive election, is one of the 35 signatories of a petition launched on July 19 calling on Lam to show political courage to resolve the current impasse.

He said Lam had been “a government official who cared most about public consultation”, hence the dissonance with her seemingly cavalier approach to seeking opinions over the bill. Ng had a close working relationship with Lam from 2007 to 2012, when she, as development secretary, steered several major public engagement exercises, including those for formulating a new strategy for urban renewal and plans for a vibrant harbourfront.

After all the prosecutions, was the Occupy movement in vain?

A person close to the administration said Lam and her officials were deceived by previous successes such as the easing of fears over the “co-location” of joint immigration and customs arrangements at the West Kowloon terminus for the express rail link to the mainland after it opened last September.

“They believed dissenting voices would die down once the bill was passed,” the person said.

But even as the feedback mechanisms are due for an overhaul, political watchers also warned the government not to think this was all that was needed. “It would be dangerous to reduce the solution to something technical like doing more polls,” he said.

“The failure was in pressing ahead at all cost. The government must look deeper in its soul-searching,” he said.

Tam Kwok-kiu, a walking encyclopaedia of district politics with his experience as a councillor for more than three decades, doubted the government would learn its lesson. “If the government doesn’t change its mindset of not wanting to listen, it won’t help much, no matter how many times they meet district councillors or how many surveys they conduct.”

Additional reporting by Joyce Ng

Other parts of this series have examined what Hong Kong protesters really want, why protesters view the police as the enemy, and why does Beijing keep getting Hong Kong wrong?