Britain proposed to boost Hong Kong’s autonomy after return to Chinese rule in 1997 through de facto constitutional court, files show

- London urged Beijing in 1989 to turn the Basic Law Committee into a de facto constitutional court, newly declassified British government files show

- British government also suggested allowing Hong Kong to handle any state of emergency arising from turmoil in the city with local laws

British government proposals to boost Hong Kong’s autonomy after the city’s return to Chinese rule by in effect turning an advisory panel into a constitutional court met with strong reservations from Beijing, according to newly declassified files.

The British government also suggested allowing Hong Kong to handle any state of emergency arising from turmoil in the city with local laws, rather than applying national ones.

Those two proposals to boost the city’s autonomy after 1997 were among a number of suggested amendments to the second draft of the Basic Law.

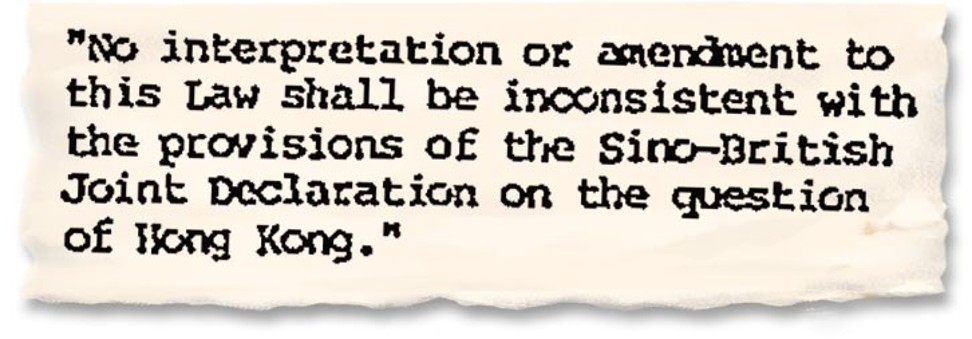

The files also showed London proposed in the wake of the 1989 Tiananmen Square crackdown that a new article be added to the Basic Law stating that no interpretation or amendment to the city’s mini-constitution should be inconsistent with the provisions of the Sino-British Joint Declaration, an agreement signed in 1984 to settle the future of Hong Kong.

Beijing officials have slammed pro-independence protesters for challenging national security, while British politicians had questioned whether the Chinese government has been complying with the 1984 declaration when dealing with Hong Kong affairs.

In recent years, Hong Kong’s opposition legislators have also criticised the Basic Law Committee for being not transparent or influential enough on Beijing’s handling of issues related to the mini-constitution.

British officials’ “overall critique” of the Basic Law draft, released in February 1989, noted the committee would play an important role in resolving matters concerning the division of power between Beijing and the local administration after 1997.

“But the present proposal for the establishment of the Basic Law Committee is silent on its work procedure,” the document said.

The critique was sent from the Hong Kong government to Britain’s Foreign and Commonwealth Office on October 26, 1989.

The 12-member committee, which advises the Chinese legislature on the interpretation and amendment of the Basic Law, is a working group under the National People’s Congress Standing Committee, the nation’s top legislative body.

Six members are from mainland China and the others from Hong Kong.

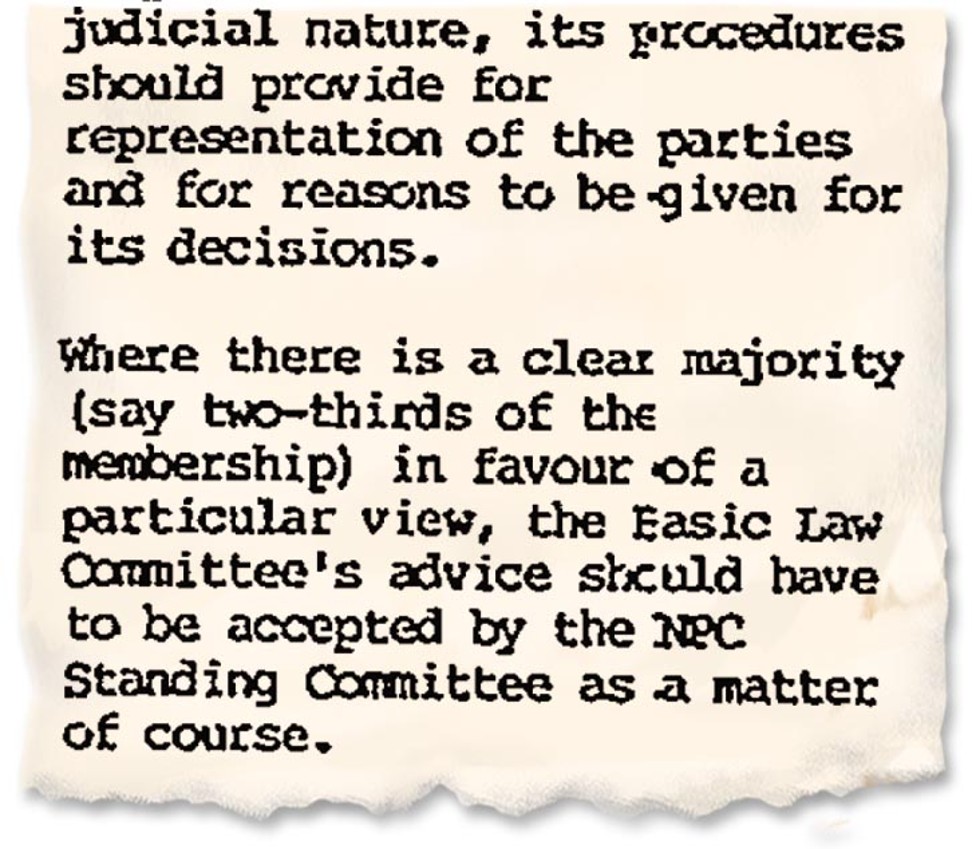

The 1989 document said: “The committee's working procedures should be as open and formal as possible. Where it performs a function of a judicial nature, its procedures should provide for representation of the parties and for reasons to be given for its decision.

“Where there is a clear majority (say two-thirds of the membership) in favour of a particular view, the Basic Law Committee’s advice should have to be accepted by the NPC Standing Committee as a matter of course.”

The idea came close to suggesting the committee be modelled on a constitutional court, according to the document.

The British government had also told Beijing of the need for detailed provisions in the Basic Law on the committee’s work procedures.

But the document said the Chinese side had expressed strong reservations about setting up a constitutional court for matters arising from the Basic Law.

On April 4, 1990, the NPC endorsed the final version of the Basic Law after a five-year drafting process. It states that the NPCSC shall consult the Basic Law Committee before interpreting the city’s mini-constitution and the panel shall study a bill for amending the Basic Law before it is put on the NPC’s agenda. But the mini-constitution does not detail the committee’s work procedures.

Since 1997, Hong Kong politicians and academics have urged the Basic Law Committee, which does not give the rationale for its advice to the NPCSC, to increase transparency of its operations.

The British records, which were meant to be sealed until January 2049, were declassified last month following a freedom of information request from the Post.

According to the records, the British government also argued there was no need for Beijing to apply relevant nationals laws to Hong Kong to deal with emergencies arising from turmoil in the city after 1997 as there were already existing laws to handle such situations.

The document suggested revising Article 23 of the Basic Law draft in such a way that Hong Kong “shall by its own legislation prohibit any act of treason, secession, sedition or theft of state secrets and provide for any state of emergency”.

The article in the final version of the Basic Law reads: “The HKSAR shall enact laws on its own to prohibit any act of treason, secession, sedition, subversion against the Central People’s Government, or theft of state secrets … and to prohibit political organisations or bodies of the region from establishing ties with foreign political organisations or bodies.”

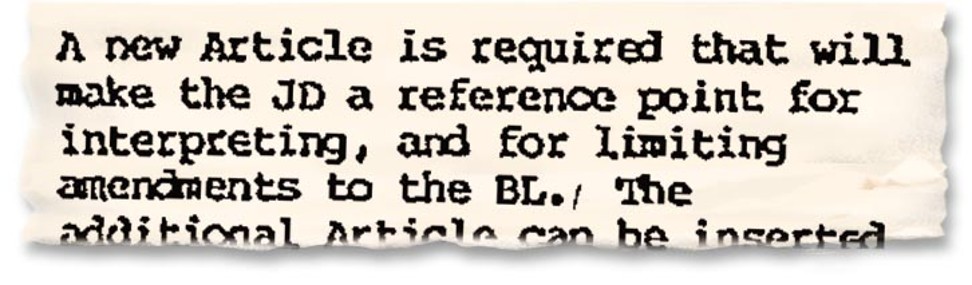

“A new article is required that will would make the Joint Declaration a reference point for interpreting, and for limiting amendments to the Basic Law,” the document said.

A new clause stating that “no interpretation or amendment to this Law shall be inconsistent with the provisions of the Sino-British Joint Declaration” could be inserted into the Basic Law.

The Joint Declaration states that China’s basic policies regarding Hong Kong, which “will remain unchanged for 50 years” after resumption of control in 1997, include the promise that the city will retain a high degree of autonomy.

The basic policies are detailed in Annex I and stipulated in the Basic Law. Whether the declaration is still valid remains a bone of contention.