British-era Special Branch offers a hint of how local and mainland Chinese agents could help enforce Hong Kong’s new security law

- Key concerns include how exactly the mainland agents will work, whom they will be answerable to and whether Hong Kong authorities will have oversight of them

- Special Branch of police monitored suspect activities, groups, individuals for decades

In the final installment of a three-part series on Beijing’s move to create a new national security law for Hong Kong, we look at the past precedent of a secret colonial police outfit.

Key concerns include how exactly the mainland agents will work, whom they will be answerable to and whether Hong Kong authorities will have oversight of their activities.

What it means when Beijing draws up national security law for Hong Kong

00:50

Donald Trump announces US will revoke Hong Kong’s special status

Hinting at what the enforcement mechanisms could look like, pro-Beijing heavyweights have pointed to the Special Branch, the intelligence-gathering unit from Hong Kong’s colonial era.

A feature of British administration across its former colonies, the Special Branch was a secret unit dedicated to gathering information on activities, individuals and groups considered potential threats to security and the interests of the colonial master.

Legal experts question Hong Kong’s new national security law

“Singapore has a Special Branch. We don’t. America has all kinds of law enforcement agencies that are tasked to deal with national security threats. We don’t. So it’s not surprising that as part of the efforts to fill the national security legal gap, we need to have a body,” Leung told Reuters.

“There is a possibility … of the central people’s government authorising Hong Kong law enforcement bodies, such as the police, to enforce the law.”

Other pro-establishment figures who suggested the same included Lau Siu-kai, vice-president of Beijing’s top think tank on Hong Kong, and former justice minister Elsie Leung Oi-sie, a former vice-chairwoman of the Basic Law Committee, which advises the national legislature on the city’s mini-constitution.

But some legal academics and opposition lawmakers were fearful, saying China’s intelligence agencies enjoyed sweeping powers on the mainland, and warning that Hong Kong could enter a new era of suppressive political policing.

‘Collect, collate, assess intelligence’

The origins of the Special Branch in Hong Kong can be traced back to the 1920s when the British established an Anti-Communist Squad within the Criminal Investigation Department of the police force, to monitor Communist Party organisations and activities.

The squad was renamed the Special Branch in 1933, and was referred to as the “Political Department” in Chinese, as it mainly carried out “preventive political policing” to suppress subversive elements, according to a study by University of Hong Kong (HKU) law professors Fu Hualing and Richard Cullen.

Records show the Special Branch was mainly made up of British officers who gathered intelligence and raided protests and strikes organised by communists.

Spying and surveillance was a key task. Many members of the Communist Party in Hong Kong and pro-China organisations had their homes bugged by the Special Branch, according to political scientist Steve Tsang in his book Government and Politics.

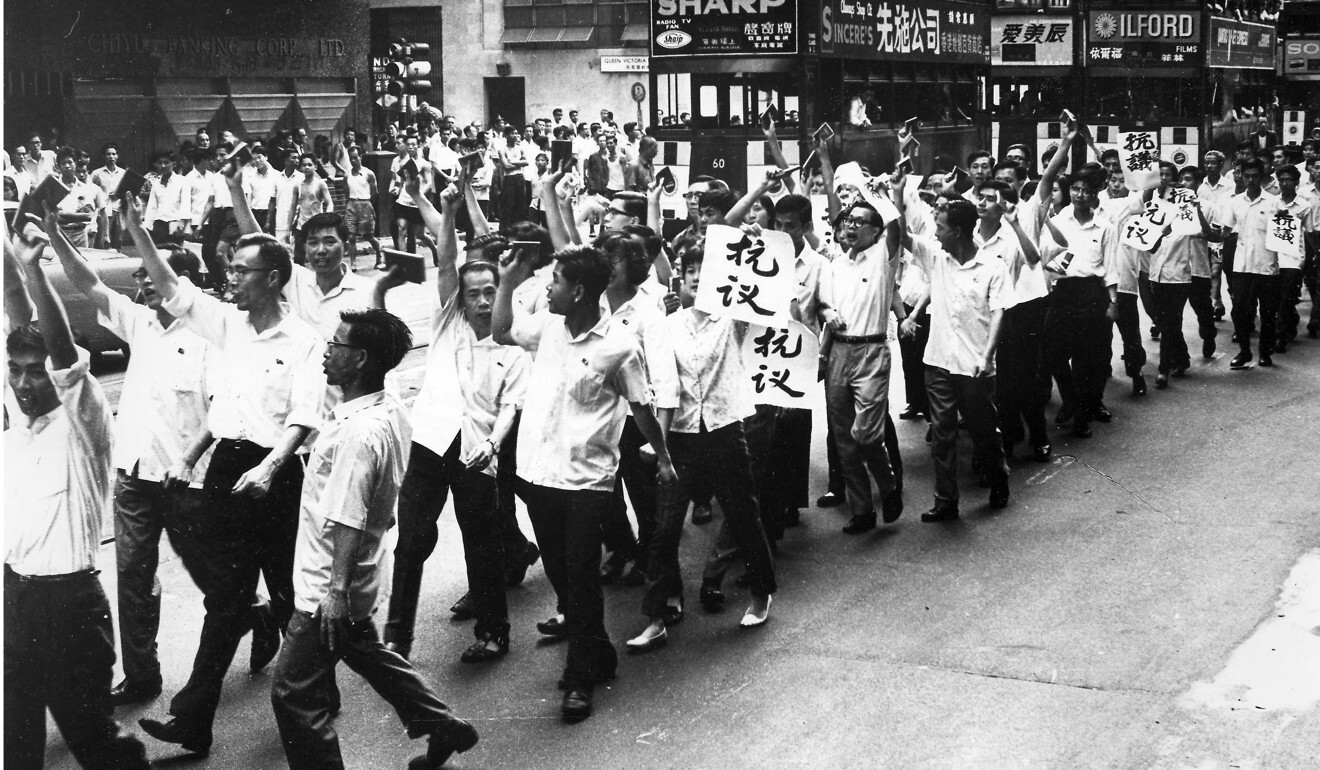

Ray Yep Kin-man, a political scientist at City University, said he interviewed a former Special Branch officer who told him it searched left-wing premises during the 1967 riots. The disturbances, instigated by the left wing in Hong Kong, erupted a year after Chinese leader Mao Zedong launched the Cultural Revolution.

Explainer: what it means when Beijing draws up national security law for Hong Kong

“At that time, the Special Branch was concerned about Beijing’s intentions and hoped to find useful information revealing its plans,” Yep said, recalling what the retired officer told him.

Police annual reports outlined the missions carried out by the branch, including “the prevention and detection of subversive and espionage activities and the collection, collation, assessment and dissemination of intelligence”, according to a 1976 report.

The branch was also involved in passport control and immigration, the HKU study said. In the 1980s, it carried out political vetting of senior government officials, checking whether they had been involved in student movements or had relatives working in leftist groups.

The chief of the branch wielded considerable power. A person familiar with its operations said it was led by a deputy police commissioner who reported directly to the commissioner and the colonial governor.

“The branch … did work closely with British and other friendly intelligence agencies,” the source said.

Yep said the head of the Special Branch was a member of the high-level local intelligence committee, which included the commander of the British forces and the secretary for security.

“MI5, the British government’s intelligence agency, was kept well informed of the operations of the Special Branch at the time,” he said.

The branch remained in operation until 1995 when Hong Kong’s pre-handover government reorganised it into the police force’s Security Wing with limited functions such as counterterrorism retained.

It monitored the same areas as the Special Branch, but the Security Wing has clearly failed to be effective

During the handover talks in the 1980s, the colonial government decided to disband the branch as it feared sensitive information would be handed over to China after the handover. Britain also feared that British officers who had worked against the communists would be persecuted, according to the HKU study.

After the 1997 handover, the Security Wing focused on local pressure groups, trade unions, counterterrorism activities and VIP protection, said the source familiar with Special Branch operations.

“It in fact monitored the same areas as the Special Branch, but the Security Wing has clearly failed to be effective,” the source said.

Veteran Democratic Party lawmaker James To Kun-sun claimed that despite the sensitive nature of its operations, the Special Branch was not controversial and did not affect the lives of ordinary citizens much.

But during the handover period, public pressure mounted on the local government to improve transparency when the branch was transformed into the Security Wing.

Legislative Council records show that in 1996, lawmakers on the security panel, including To, who was its chairman, grilled police on the work done by the wing. Another pan-democrat, Emily Lau Wai-hing, called for a mechanism to “monitor the work of secret intelligence agencies on behalf of the community”, as in democracies.

Hong Kong ministers step up defence of Beijing’s national security law

To recalled that police later agreed to brief legislators on the wing’s work regarding witness protection and anti-terrorist activities.

The government also reassured lawmakers that the wing was governed by the Police Force Ordinance, and its work had to be done in accordance with Hong Kong law.

However, To has criticised the Security Wing for many years for the lack of reports on its work and the exemption it enjoys from being audited.

Would the same latitude be given to the mainland agents sent to Hong Kong to help enforce the new national security law, he asked, warning that it would be even more difficult to hold them to account, given the sweeping powers of the Chinese intelligence agency.

He was referring to China’s Ministry of State Security (MSS), which has broad powers to investigate individuals and institutions, and arrest foreigners and citizens alike for crimes involving national security.

Hongkongers renew their rush for foreign property and passports

Liu, the late Nobel Peace Prize laureate, was jailed for 11 years on subversion charges after drafting a manifesto calling for political reform in China. His wife, Liu Xia, was placed under house arrest for eight years.

But Basic Law committee vice-chairwoman Maria Tam Wai-chu expected such agents to work with Hong Kong police in investigations that “could be joint efforts”.

Police from outside Hong Kong would need “approval” from local authorities to conduct investigations, she told local media. “And you cannot investigate on your own.”

“I’m not worried about anybody being arrested by a police officer from the mainland and then taken back to China for investigation or punishment,” Tam added.

“It is not, not, not going to happen.”

01:54

Hongkongers with BN(O) passports could be eligible for UK citizenship if China imposes security law

‘Mainland agents might help’

Beijing announced last week that it would draw up the law for Hong Kong to “prevent, stop and punish” threats to national security by outlawing acts of secession, subversion, foreign interference and terrorism in the city’s affairs.

Beijing’s agencies, the Hong Kong government and pro-establishment figures responded by slamming foreign countries and politicians for applying double standards, as many countries have national security laws and established intelligence services.

Pro-Beijing camp plays down US sanctions against Hong Kong

Former HKU law dean Johannes Chan Man-mun was not optimistic that mainland agents stationed in Hong Kong would be transparent about their work or accountable to city authorities.

Nor did he expect that in drafting the new law, Beijing would be precise in spelling out the powers allocated to Hong Kong police and the central government.

“It is not the practice on the mainland to clearly define the powers of law enforcement agencies,” he said.

Lau Siu-kai, vice-president of the Chinese Association of Hong Kong and Macau Studies, said that as the new law expanded the powers of China’s security services, mainland agents might be given enforcement powers when operating in the city.

‘False and wrong’ to say Hong Kong has lost autonomy: justice secretary

Given the MSS’s established mechanisms for “tackling all sorts of national security issues,” he said mainland agents could help the local authorities not only to quash unrest, but also improve their ability to identify threats early.

“It’s not a bad thing if mainland agents can directly share experiences with key local departments that handle sensitive information, such as customs and the Immigration Department, to stay alert to potential threats,” he said.