Explainer | Hong Kong national security law questions and doubts remain. Here’s what we do and don’t know

- We don’t know when the law will be passed but we do know the NPCSC is meeting this week

- With questions swirling over enforcement and jurisdiction, legal experts and lawmakers want more information made available

Deng Zhonghua, deputy director of the State Council’s Hong Kong and Macau Affairs Office (HKMAO), became the first Beijing official to provide details of the framework on Monday when he said Beijing could hold jurisdiction over cases “in very special circumstances” when applying the new law, which would not be used retroactively.

While Deng left many questions unanswered, legal experts and lawmakers in Hong Kong have called for more information before the legislation is passed. Here are some of the questions raised, what experts say, and what is known and not known so far.

When will the law be passed?

What we know: The NPCSC is scheduled to meet from Thursday to Saturday. While the law was not on its official agenda, Tam Yiu-chung, Hong Kong’s sole representative to the body, said the item “could be added at the last minute”. On Tuesday, Yue Zhongming, spokesman for the Legislative Affairs Commission of the NPCSC said formulation of the law would be sped up.

What we don’t know: Tam remained tight-lipped about whether the law would be discussed this week. The NPCSC holds meetings every two months, with the next one in late August. But promulgating the law after that could worsen public opposition, affecting the chances of the pro-establishment camp in the Legislative Council elections scheduled for September, sources in the bloc said.

That leaves the possibility the NPCSC might hold a special meeting in July to pass the bill, according to a source. But two scholars of Chinese law, Fu Hualing at the University of Hong Kong and Ling Bing at the University of Sydney, expressed hope Beijing would listen to the views of Hongkongers and spend at least three meetings to scrutinise the bill.

Will cases be handled solely by Hong Kong courts?

What we know: While Secretary for Justice Teresa Cheng Yeuk-wah had offered assurances Hong Kong would have the main responsibility for prosecution and judicial work, Deng said Beijing would retain jurisdiction in special circumstances involving “very, very few” cases related to serious damage to national security.

What we don’t know: It remains unclear how Beijing will draw the line between serious and ordinary cases, and define the scope of jurisdiction. Tam said the exceptional cases mentioned by Deng related to defence and foreign affairs, areas outside the jurisdiction of local courts under Article 19 of the Basic Law, the city’s mini-constitution. Residents who breached the law could be extradited to mainland China for trial “if Beijing found it necessary that the case should not be handled by Hong Kong courts”, Tam said.

Extradition to mainland China may be possible under new Hong Kong national security law

Former Basic Law Committee member Rao Geping said Beijing’s jurisdiction over serious Hong Kong cases included law enforcement and judicial powers. Ling Bing, of the University of Sydney’ s law school, said splitting jurisdiction would prove a tricky balancing act. “There is a huge difficulty in ensuring Hong Kong’s judicial power while reserving Beijing’s jurisdiction over some serious cases,” he said.

02:17

How China is drafting a new Hong Kong national security law at the National People’s Congress

Will the law be retroactive?

What we know: Both Beijing and Hong Kong officials have said the legislation will not be used retroactively.

What we don’t know: Controversy may arise in identifying when crimes first occurred. Simon Young Ngai-man, a law professor at HKU, said that might involve counting back to when the offence was criminalised in mainland China or at least when the National People’s Congress passed the resolution sending the legislation to the standing committee on May 28.

How will the law be compatible with Hong Kong’s common law system?

What we know: Justice chief Teresa Cheng has effectively dismissed calls from the Bar Association to ensure the law accords with the city’s common law system, calling the suggestion “impractical”. Deng said the new law had to be compatible with the mainland’s national security laws, anti-terrorism law, criminal law, criminal procedure law and other national laws. He said a law passed by the country’s top legislative body “has the authority and status that cannot be challenged” and no local laws should override it.

Hong Kong protests: one year on, with the national security law looming, has the anti-government movement lost?

Civic Party leader Alvin Yeung Ngok-kiu, a barrister, argued Hong Kong’s common law system could not be compatible with national laws applied in mainland China. “Huge differences exist in legal principles and spirit. [Beijing] can’t simply parrot the mainland Chinese law and say it’s compatible with the Hong Kong legal system,” Yeung said, noting the Legislative Council had passed its own legislation localising mainland China’s national anthem law.

HKU legal scholar Johannes Chan Man-mun said if the law was made compatible with national laws, Hongkongers could lose protection of legal rights guaranteed under the common law system.

Who will be responsible for enforcing the law?

What we know: Under the legislation, the Hong Kong government is required to set up new institutions to safeguard national security and allow mainland Chinese agencies to operate in the city “when needed”.

Security chief John Lee Ka-chiu said the city’s police had set up a dedicated unit to enforce the law, which would be ready “on the very first day” the legislation came into effect.

Deng said the establishment of a mainland Chinese national security agency in Hong Kong was the “unequivocal demand” set out by the NPC and it must be granted necessary powers and funding to enforce the law. The new branch will be directly “supervised and guided” by mainland Chinese security agencies, with a coordination mechanism between the two enforcement bodies.

What we don’t know: The roles and powers of the local police unit and the new mainland Chinese security agency remain unspecified. For instance, will local police pass on surveillance findings and intelligence to their mainland Chinese counterparts? Can mainland agents be held accountable by Hong Kong authorities? How exactly will they coordinate their efforts?

While senior advisers to Beijing, including former Basic Law Committee vice-chairwoman Elsie Leung Oi-sie, said mainland Chinese agents would not be above local law, Johannes Chan was sceptical, given their “poor track record”.

He noted Hong Kong’s situation was different from Western democracies, such as Britain and the United States, where the legislative and the executive branches were responsible for holding intelligence services accountable.

“Do we realistically expect the head of this national security organisation in Hong Kong will appear before Legco for questioning and so on?” Chan said. “I doubt it.”

Ling Bing suggested the law should limit the role of mainland Chinese agents to gathering intelligence and collecting evidence, while leaving arrests to local police.

Will juries hear trials?

What we know: Sources close to the central government said Beijing was wary of having a jury hear cases concerning the new law.

While Regina Ip Lau Suk-yee of the New People’s Party was against allowing jurors hear cases, pointing to possible difficulties in finding “truly impartial” jurors, Ronny Tong said jury trials for all cases involving serious crimes at the High Court was standard procedure. “There must be strong grounds to conduct a hearing without a jury,” he told the Post, but said closed-door trials for cases involving state secrets would be acceptable.

The Bar Association warned that defendants should be afforded the right of a jury trial given the “seriousness of the offences” under the new law.

Hong Kong’s ‘second return’ to China will be easier said than done

What will be prohibited under the new law?

What we know: The law aims to prevent, stop and punish four offences – secession, subversion of state power, terrorism and foreign interference in the city. Zhang Yong, vice-chairman of the Basic Law Committee, said rather than focusing only on traditional and territorial threats, China must also manage risks in areas ranging from finance to internet and nuclear security.

What we don’t know: The definitions of the four offences have not been clearly delineated by mainland or local officials, despite the Bar Association saying offences should be narrowly defined.

Subversion is not addressed under existing Hong Kong laws, although national security legislation the government tried to launch in 2003 did cover it. The charge has been broadly applied in mainland China.

Under the 2003 bill, it was defined as acts to intimidate or overthrow the central government or undo the basic system of the state by serious unlawful means, according to the consultation document. It remains unknown how Beijing will define the offence in view of the social unrest in Hong Kong that has included calls for revolution.

Under China’s Penal Code, inciting subversion of state power has been used to prosecute human rights lawyers and activists in a sweeping crackdown beginning in 2015.

Article 4 of the 1993 National Security Law defines secession as an “act endangering state security” as any of several enumerated activities, including “dismembering the state”.

But as secession lacks legal precedent in Hong Kong, it leaves Beijing to draw the line on what will constitute the crime, which could include activities relating to self-determination and support for independence in Taiwan.

02:22

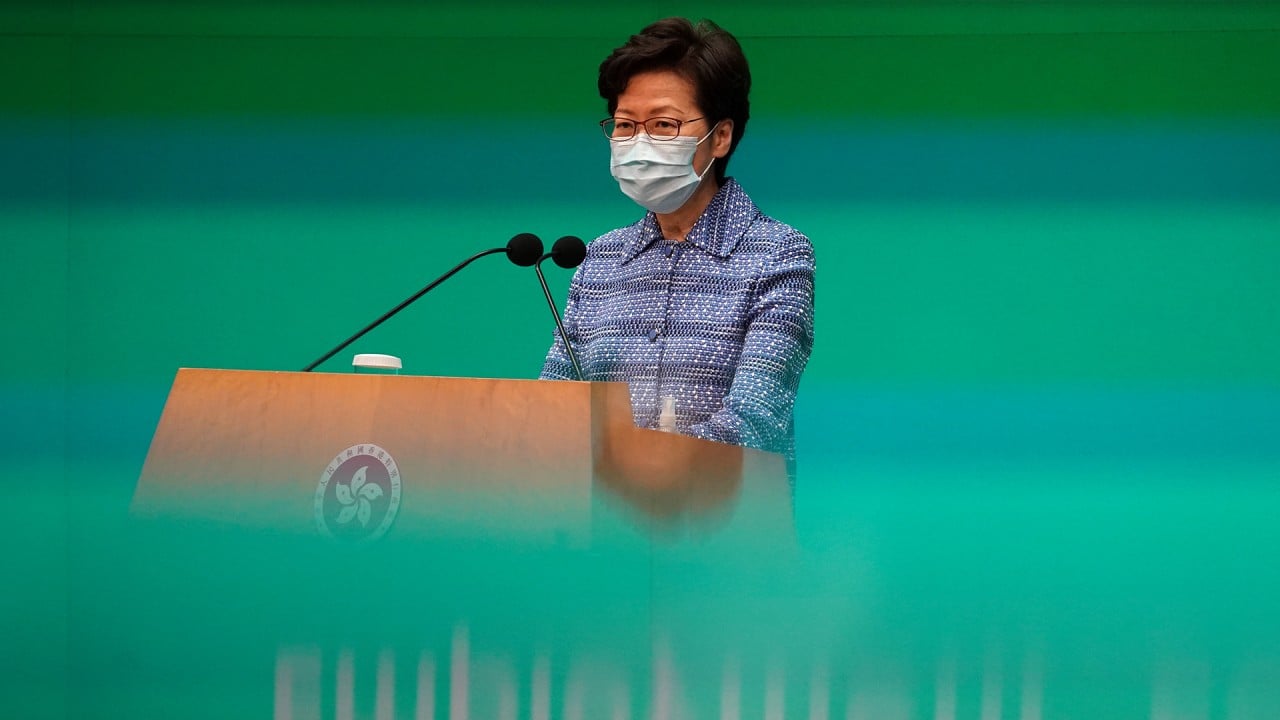

Hong Kong freedoms will not be eroded by Beijing’s national security law, Carrie Lam says

Could the law encompass speech?

What we know: Zhang Xiaoming, the deputy director of the HKMAO, said the law would not be used to “frame people up” and would only target the “very few” people threatening national security.

What we don’t know: Will chanting slogans, commenting on social media and creating artistic expressions be policed under the law? Regina Ip said she believed a person would not be prosecuted for remarks not accompanied by action, saying “speech crimes” did not exist in common law. Delegate Tam Yiu-chung believed law enforcement bodies would investigate whether speeches were backed by organised acts.

Under that draft legislation of Article 23 in 2003, a person is guilty of secession if he or she withdraws any part of China from its sovereignty by “using force or serious criminal means” that seriously endangered the country’s territorial integrity.

Fu Hualing of HKU said he hoped the standing committee would draw reference from the 2003 proposal, which was relatively liberal and lenient.

“The law must differentiate discussion in the private sphere and public domain,” he said. “It should also draw a line between expression of views in peaceful manner and advocacy of political objectives by using force.”