Explainer | Hong Kong elections: what does it mean to be disqualified, who decides, and how have hopefuls been barred in the past?

- National security law objections and plans to leverage a first-ever Legco majority among reasons cited by officials who made the call

- The Post looks at what is at stake in 2020 and the city’s recent history of disqualifications

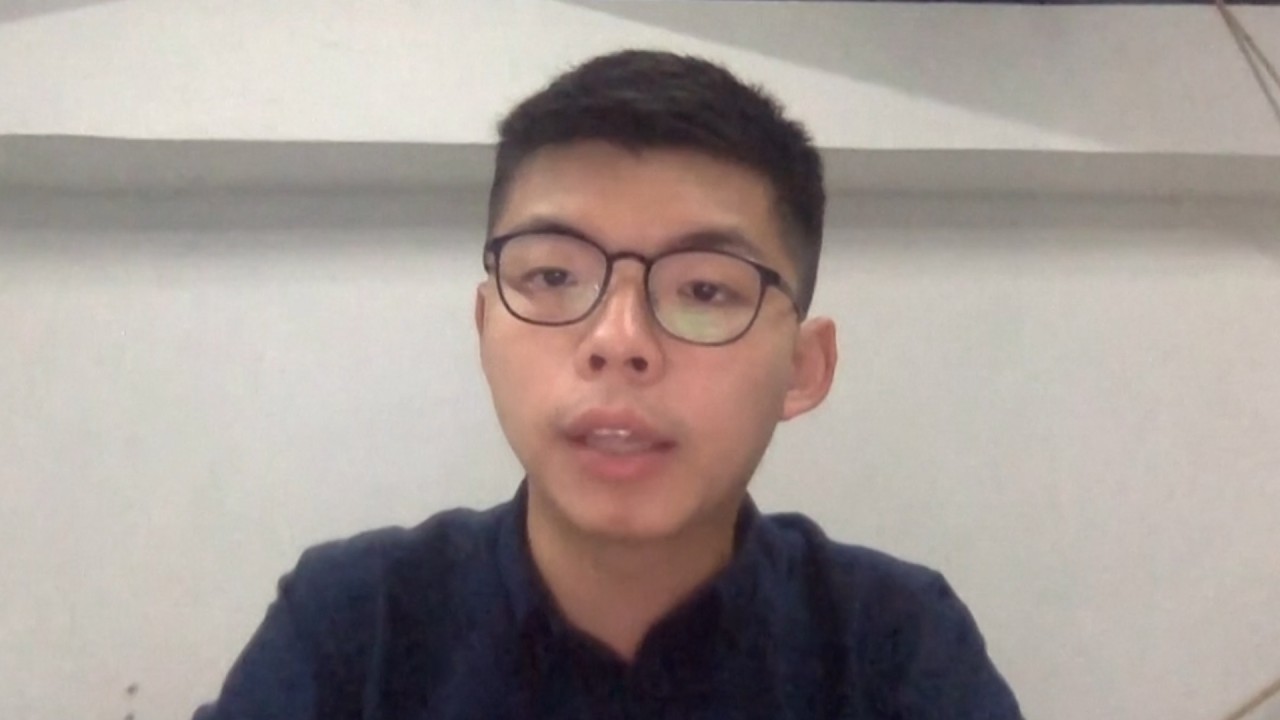

Among the dozen ousted were not only young activists such as Joshua Wong Chi-fung, who have previously called for the city’s self-determination, but also veteran incumbent lawmakers who lobbied foreign politicians to sanction Hong Kong officials in the wake of last year’s anti-government protest.

The group’s stated objection to the sweeping new national security law imposed by Beijing was also taken into account in the rejection of their bids.

This is not the first time opposition candidates have been disqualified, however. Hong Kong has a record of invalidating would-be electoral candidates as well as disqualifying sitting lawmakers deemed to have crossed certain red lines.

Below, we examine why the dozen aspirants were rejected on Thursday, before looking back at past instances of disqualification and what is now at stake if elections are held as planned.

Who has been disqualified this time?

They include four incumbent lawmakers – the Civic Party’s Alvin Yeung Ngok-kiu, Dennis Kwok and Kwok Ka-ki, as well as accountancy sector lawmaker Kenneth Leung.

Political activists Wong, former Occupy student leader Lester Shum, Ventus Lau Wing-hong, Gwyneth Ho Kwai-lam and Alvin Cheng Kam-mun, along with district councillors Cheng Tat-hung, Tiffany Yuen Ka-wai and Fergus Leung Fong-wai also had their candidacies invalidated.

Returning officers who vetted their applications told them they were looking at whether they had “an intention to support, promote and embrace” the Basic Law, and not simply whether they would “uphold” the city’s mini-constitution as previously required.

What are the reasons for their disqualification?

Three reasons can be summarised. The most common one is the hopefuls’ stated objection to the national security law.

For example, a vetting officer cited a joint statement by Wong and other candidates, which said that the “resistance bloc” would oppose the new law “without any hesitation”.

While Wong argued that existing laws were sufficient for the government to discharge its constitutional duty to safeguard national security and the new law was in conflict with the Basic Law, the officer found his claim “not worthy of belief”, noting that Wong had described the law as “evil” before its enactment and called for greater international pressure on China over the legislation.

The second reason relates to their vows. Most of the candidates had vowed that, if the camp was able to secure a majority in Legco, they would seek to veto the government budget and force the government to accede to their “five demands”, including universal suffrage.

01:31

Joshua Wong reacts to his disqualification from running in upcoming Hong Kong elections

In ruling for Civic Party leader Alvin Yeung, for example, the returning officer told him that since Yeung did not indicate he would give up that plan, she was not convinced he “genuinely and truthfully” intended to uphold the Basic Law and pledge allegiance to the city.

The third reason was lobbying foreign governments to intercede in Hong Kong affairs. Officers noted a March trip by Kenneth Leung and lawmakers from both camps to the US, where he and two other opposition lawmakers discussed appealing to the US government to impose sanctions on Hong Kong under the Hong Kong Human Rights and Democracy Act.

The returning officer noted while Leung “might not be directly requesting or appealing for US sanctions actions [like other pan-democrats], the supportive or assistive role he played in pursuing the [sanctions] is clearly far from meeting the … requirement” to uphold the Basic Law.

When was the first time an invalidation took place?

Hopefuls prior to the September 2016 elections also risked having their candidacies invalidated, but mostly for administrative reasons, not because of their political stance. They may have failed to fill in a proper registration form, for instance.

But things changed. Before that election, then localist student leader Edward Leung Tin-kei was permitted to run in a New Territories East by-election in January.

Will Legislative Council polls be postponed, and who stands to gain?

But in the weeks leading up to the September polls, candidates were required to sign an additional declaration form acknowledging that Hong Kong was an inalienable part of China, as stipulated in the city’s mini-constitution, the Basic Law.

Six hopefuls were ultimately barred from running, including Leung. However, the role of the new form was unclear, as some pan-democrats were allowed to run despite not signing it. Leung, meanwhile, who did sign it, was barred from running because the government officer who vetted him did not believe he had genuinely changed his stance.

Who are the vetting officers?

The applications by aspirants are screened by about a score of returning officers, who are administrative officers working for the government, appointed by the Electoral Affairs Commission.

In the case of a Legco election, their power stems from the Legislative Council Ordinance, which requires them to check whether candidates fulfil, among other things, the age, nationality requirements, and the signing of a declaration “to the effect that the person will uphold the Basic Law and pledge allegiance to the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region”.

The government has come under fire for asking civil servants to administer a law that gives them potentially wide discretionary powers.

Who else have they invalidated in the past?

Following the 2016 Legislative Council elections, the city held two by-elections in 2018, one in November for a Kowloon West seat, and an earlier one in March for seats in Kowloon West, New Territories East, Hong Kong Island and the professional sector of architectural, surveying, planning and landscape.

Five opposition candidates were invalidated in those two by-elections, including Agnes Chow Ting, prominent activist Joshua Wong Chi-fung’s comrade-in-arms, because their now-defunct group, Demosisto, advocated “self-determination”.

Then in 2019, when the city held its district council elections, Wong was also invalidated.

What were the legal disputes about?

Several excluded hopefuls have lodged election petitions to the court in the past.

Their argument centred on whether the returning officer, as a civil servant, had the power to determine whether the pledge to uphold the Basic Law, as made through the declaration form, was bona fide.

Such a power could amount to political censorship, they argued. Or rather, the officer’s job was merely administrative, in that they only had to make sure such a form was signed and submitted properly.

Hong Kong’s court has ruled that the officers do have the power to scrutinise these forms in substance, although it has also sided with a few hopefuls in finding that some officers failed to give them ample opportunity to explain themselves.

In any event, those rulings have often been too late for aggrieved hopefuls to seek a new election, as cases often take up to years to progress through the courts.

Carrie Lam ‘meets cabinet’ to discuss postponing Legislative Council polls

What will be the actual impact?

The opposition camp expects more aspirants will be ousted, as the dozen disqualified on Wednesday were among those who submitted their bids the earliest. They believe others who shared the same beliefs will likely be rejected.

Lau Siu-kai, vice-president of semi-official Beijing think tank the Chinese Association of Hong Kong and Macau Studies, had previously predicted the new law could lead to more invalidations as it would impose more hurdles for candidates to clear.

Political scientists, meanwhile, said that the large-scale disqualifications would have a chilling effect on politicians, including moderates, as even talking about blocking major bills or paralysing the legislature was now seen as a red line.

Given the new criteria, the Civic Party said that even their backup candidates, or so-called “Plan Bs”, would have no chance to appear on ballots.

The disqualifications have also revealed Beijing’s expectation of lawmakers. Citing late paramount leader Deng Xiaoping, the Liaison Office said in a statement that the bottom line of “Hong Kong people governing Hong Kong” was that the city must be governed with “patriots as the main body”.