National security law and Hong Kong’s opposition camp: down but not out, can bloc reinvent itself as a loyal Beijing critic?

- The mood in Hong Kong’s pan-democratic camp is despondent, with 55 opposition activists arrested under the national security law

- Experts feel it will be tough for the parties to survive for long in the face of crackdown, but they could gradually become pressure groups

With Beijing insisting only “patriots” can run Hong Kong, what does the future hold for the city’s fragmented opposition? In the second of a two-part special report, we examine the state of the opposition and whether it can survive the political tsunami sweeping over it. You can read part one here.

This is not how it was supposed to be for Hong Kong’s opposition parties.

Their plan for “35-plus” reflected how much within grasp winning a majority of the legislature’s 70 seats seemed. That victory would have had implications for the 2022 race to choose the city’s chief executive.

Then it all unravelled.

In November, four opposition lawmakers were disqualified from Legco, prompting all 15 others from the bloc to resign en masse in protest.

Last month, the authorities arrested 55 former lawmakers and activists on suspicion of subversion under the national security law for their alleged goal of paralysing the government with their 35-plus drive. The crackdown led many to conclude that Beijing was intent on annihilating Hong Kong’s opposition camp.

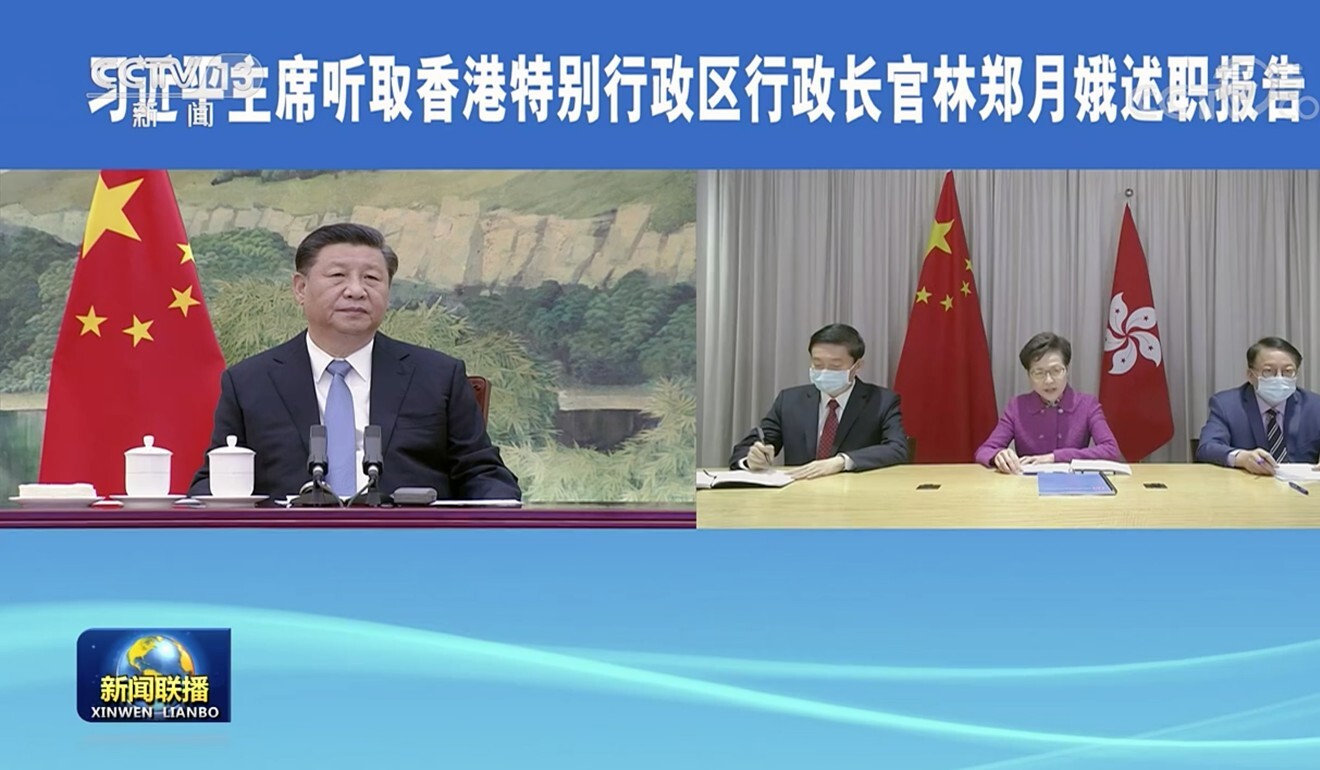

Then came President Xi Jinping’s reminder last month that Hong Kong must be run by “patriots”. He used the catchphrase, “Patriots governing Hong Kong”, that has become a mantra among pro-establishment politicians.

But for the opposition, the phrase held a dark hint of more curbs on elections in the city.

Things have changed so much that now a democrat in Hong Kong feels blissful simply because he or she is not behind bars or does not have to go into exile yet

Former Democratic Party lawmaker Lam Cheuk-ting, one of the 55 arrested under the national security law, said the streak of recent events had made opposition legislators realise their roles and functions had changed fundamentally.

“The legislature is no longer our battlefield. It might merely be an official platform for us to exercise our official dissent, but that’s it. It no longer allows real checks and balances to hold the government accountable,” he said.

Opposition politics, he felt, was proving to be a costly exercise.

“You have to be mentally prepared for disqualification from standing in elections, bankruptcy if you are unseated, and even arrest,” he said. “Things have changed so much that now a democrat in Hong Kong feels blissful simply because he or she is not behind bars or does not have to go into exile yet.”

Lam is among pan-democrats who have sold their property to have enough money for legal fees in coming court cases and to send their children abroad. Others have quit politics and returned to their professions.

Many admit they are lost, unable to find their bearings in the new political landscape.

03:05

Public service: former Hong Kong lawmaker uses new restaurant to dish up examples of policy change

How did Hong Kong’s opposition arrive at this crossroads, struggling to see if it faces oblivion or is capable of an overhaul that will enable it to carry on?

It took a series of events and changes in the camp over the past decade to get here, pointed out Lau Siu-kai, vice-president of the semi-official Chinese Association of Hong Kong and Macau Studies.

He said the pan-democrats were regarded as a “half loyal opposition” a decade ago and that was good enough for them to be allowed to take part in elections for the chief executive and engage in dialogue with Beijing officials.

“But they turned themselves into a ‘total opposition’, which is unacceptable in the central government’s eyes,” he said.

Hong Kong patriot games: who is loyal enough in the eyes of Beijing and can critics survive the system?

Beijing has now taken a hardline approach towards Hong Kong and will give opportunities only to parties willing to play the role of a “loyal opposition”. Even candidates from the moderate Democratic Party or Civic Party might find it hard to get into Legco unless both revamped their strategies drastically, he said.

“They should no longer seek foreign help, and put into action that they support the ‘one country, two systems’ principle, respect Beijing’s sovereignty over Hong Kong and no longer challenge any resolutions handed down by the national legislature,” he said. “A lot of reforms have to be done before they can regain Beijing’s acceptance.”

The opposition also could not expect to win over Beijing and please their young supporters who insist on radical actions at the same time.

“Their dilemma is clear: if they want the support of these young voters, they can no longer participate in elections,” he added. “Or they can stay in the street and get foreign help as they wish, at the risk of violating the national security law. Such an approach, however, will only leave them as political opinion leaders without actual power.”

They turned themselves into a ‘total opposition’, which is unacceptable in the central government’s eyes

But Democratic Party chairman Lo Kin-hei dismissed allegations that his party had become more radical, insisting they had only responded in a “proportionate” way over the government’s growing intransigence.

Democrats would never be the loyal opposition Beijing preferred as it would mean becoming weak carbon copies of the pro-establishment parties, he said, rendering them irrelevant to their supporters. It was also a futile game trying to stay clear of a moving red line set at Beijing’s whim, he argued.

A camp turned upside down

From the time Britain returned Hong Kong to China in 1997, Beijing appeared to accept the presence of the city’s opposition, even if it did so half-heartedly.

Encouraged by electoral changes made by the colonial government, the opposition camp performed strongly in elections ahead of the handover.

Even then, former lawmaker and Democratic Party veteran Lee Wing-tat said his party was under no illusion that it would become Hong Kong’s ruling party.

“Some people who had greater faith in Beijing thought the central government might allow a ‘rational opposition’ to take the helm of the city,” he said, referring to the camp’s moderate faction at the time. “But we found that too naive.”

The pan-democrats claimed the retreat as their victory.

“But the central government now realised the Hong Kong government did not have the ability to take control of major political disputes,” Lee said.

The pan-democratic camp itself experienced adjustments. The Democratic Party, the oldest political party set up in 1994, now found itself eclipsed by the Civic Party, formed by lawyers and professionals who spearheaded the drive against the bill.

Then came the League of Social Democrats, a left-leaning party which held no faith in Beijing and advocated a more forceful and confrontational approach towards the authorities. It broadened the camp but also sowed the seeds of internal factionalising.

Lawmakers from the league hurled objects in Legco and resorted to filibustering to force concessions from the government, tactics not all pan-democratic legislators were comfortable with at that time.

The bloc’s unity was tested in 2010 when the city debated reforms to electoral arrangements.

The Democratic Party engaged in closed-door negotiations with Beijing officials that helped broker a compromise deal, which was eventually passed with the party’s support.

07:30

China’s Rebel City: The Hong Kong Protests

The party argued the deal could help take Hong Kong closer to achieving universal suffrage, but its allies accused it of selling out the city by striking a deal with the Communist Party and deflating the camp’s demand for full-scale reform.

New groups – such as People Power – were formed with the express aim of unseating Democratic Party candidates in the 2011 district council elections.

Lee said Beijing reneged on its promise to the Democratic Party to establish a mechanism for regular dialogue on constitutional development.

That dialogue never took place. Looking back, he said: “It was a trap. Beijing only tried to reconcile with us for strategic reasons.”

The mass sit-ins which blocked parts of the city for 79 days were unprecedented in scale and duration, but Beijing remained unmoved.

The scenes of pan-democrats fleeing the city and being thrown behind bars are not something that I imagined when I first became a lawmaker

That failure plunged the opposition camp into a season of infighting and finger-pointing, with some criticising the pan-democrats for being too mild to the point of being useless.

But by then, the radicals had appeared to join the mainstream when several of them did win in the elections. Soon enough, Beijing acted to eject six newly elected opposition lawmakers from Legco for their anti-China antics while taking their oaths.

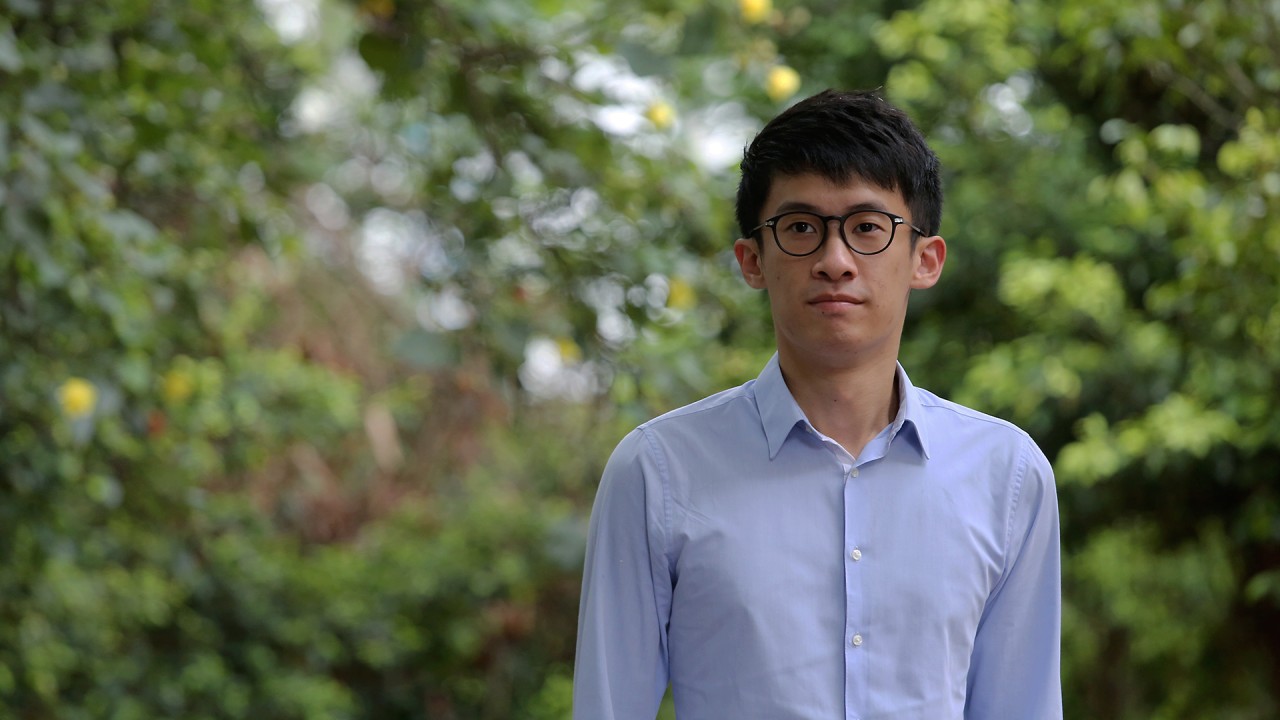

In the years that followed, more activists, including Joshua Wong, were barred from running in polls because of their political stance.

In those heady days of the anti-government movement that emerged, the opposition looked like it could be on the brink of permanently altering the political landscape. But Beijing had also run out of patience with those who appealed to overseas governments to push for sanctions against the city.

By June last year, the national security law was in place.

Last November, Beijing handed down the decision empowering the local administration to unseat lawmakers deemed disloyal to the central government. The ruling effectively removed four lawmakers – all of whom had earlier been barred from a re-election bid for allegedly calling for foreign sanctions – sparking the exit of all the other opposition members.

The Labour Party’s Fernando Cheung Chiu-hung, who was among the lawmakers who resigned, said the pan-democrats’ world had been turned upside-down within just a decade.

“Some of us used to believe that Hong Kong’s democratic system – if run smoothly after the handover – could be borrowed by other mainland cities,” said Cheung, who was elected for a term in 2004 and served again from 2012 until he quit with the others in November.

“The scenes of pan-democrats fleeing the city and being thrown behind bars are not something that I imagined when I first became a lawmaker. We were purged.”

Continuing the fight

No fewer than a dozen opposition figures fled Hong Kong for Europe, Taiwan and the United States before and after the imposition of the national security law.

The national security law has made both local and overseas Hongkongers very desperate

Many of those now overseas have chosen international lobbying and advocacy work – banned under the new law – to resist China and push for greater democracy for Hong Kong.

Now 30, he lamented that the current situation in Hong Kong made public debate over the democratic movement difficult, and said the group hoped to keep the discussion going.

Chow left Hong Kong after the Occupy protests to further his studies first in Britain and then in the United States. Although he was not at the forefront of the 2019 unrest, he was mindful that he might not be able to return.

“The national security law has made both local and overseas Hongkongers very desperate,” he said, adding that it was no longer easy for overseas Hongkongers to connect with those at home to apply pressure on the authorities. “It will inevitably increase one’s sense of helplessness.”

In the end, however, he said local activists would have to take the lead.

In Hong Kong, however, the mood in the pan-democratic camp is despondent.

It is widely expected that all 55 opposition activists arrested under the national security law will be barred from contesting elections, even if they are not charged or convicted eventually.

They include all the best performers in a round of unofficial primary polls held last year to narrow the field of opposition candidates and increase their chances of winning in the Legco elections.

If they are excluded, the opposition will lose political stars from at least two generations and must find new faces for future elections.

Had the reform [in 2015] passed, Hong Kong would have been much better than the Hong Kong of today

A once-active WhatsApp messaging group among former pro-democracy lawmakers has now gone quiet. Some members admit worrying about being arrested.

“Every time the Five Eyes impose sanctions on Beijing or Hong Kong, I can’t help but think if anyone will be arrested for this,” said a former lawmaker speaking on condition of anonymity, referring to the intelligence alliance comprising Australia, Britain, Canada, New Zealand and the US.

Another opposition source revealed that a significant number of the camp’s district councillors were now hesitant to seek a second term.

“That will be the best for Hong Kong, good for Legco and I don’t think Beijing will do anything about it,” he said.

He also said the opposition camp only had itself to blame for ruining the city’s future by voting against the Beijing-decreed political reform proposal in 2015. The stringent framework would have allowed Hongkongers to pick their leader via “one man, one vote” – albeit from a slate of two or three hopefuls vetted by a committee likely to be dominated by Beijing loyalists.

“This is absolutely the limit of how liberal it can be,” he said. “Had the reform passed, Hong Kong would have been much better than the Hong Kong of today, which is totally controlled by the central government.”

Hong Kong opposition lawmakers to resign en masse over Beijing resolution

But former Democratic Party lawmaker Andrew Wan Siu-kin said it was “naive and meaningless” to lay the blame on the underdogs, insisting the government could have avoided the whole social unrest in 2019 by withdrawing the despised extradition bill in time.

“It is those who are in power that should be blamed,” he said. “The protests had already died down when the pandemic hit the city in 2020, but the authorities still insisted on imposing the national security law on Hong Kong.”

Ray Yep Kin-man, a professor at City University’s department of public policy, said the pan-democratic parties’ survival hinged on the coming Legco polls and the election of the 1,200-strong committee which will choose the city’s leader in 2022.

“There is still a ray of hope for them if they are allowed to run in the two races. Elections are not just about political mobilisation, but also about sustaining the bloc’s momentum and exposure and keeping their supporters engaged and occupied,” Yep said.

“But if the crackdown continues, it will be very tough for these parties to survive for another two years.”

Dr Cheung Chor-yung, a senior teaching fellow at City University’s public policy department, expected Hong Kong’s opposition parties to gradually become pressure groups.

“Although it is very difficult for the authorities to crush civil society and dissident voices in Hong Kong once and for all, the opposition forces will most likely be loosely organised and hardly able to exert direct influence on government policies after losing their public powers,” he said. “I expect this situation will remain for a long while in Hong Kong.”

02:41

Former Hong Kong opposition lawmaker Baggio Leung seeks asylum in the US

Several pan-democrats agreed that their supporters’ expectations of them might change, which could result in their ditching confrontational tactics.

“They want us to maintain our strength under such intense situations and not to give the authorities any easy excuse to target us,” Lam, the former lawmaker, said.

The father of two is now earning a living from writing, running a YouTube channel and appearing in online talk shows.

He was resolute in insisting that Hong Kong’s opposition was not in its death throes, despite the odds.

“Beijing certainly wants to suppress dissident voices in Hong Kong, but whether it can completely wipe them out hinges on how many of us carry on, continue to speak out and engage in politics and not be afraid of jail,” he said.

“Every day counts. I’ll just do my best.”

Additional reporting by Lilian Cheng

Read the first part of the series, which looks at how the catchphrase ‘patriots governing Hong Kong’ is gaining currency, here.