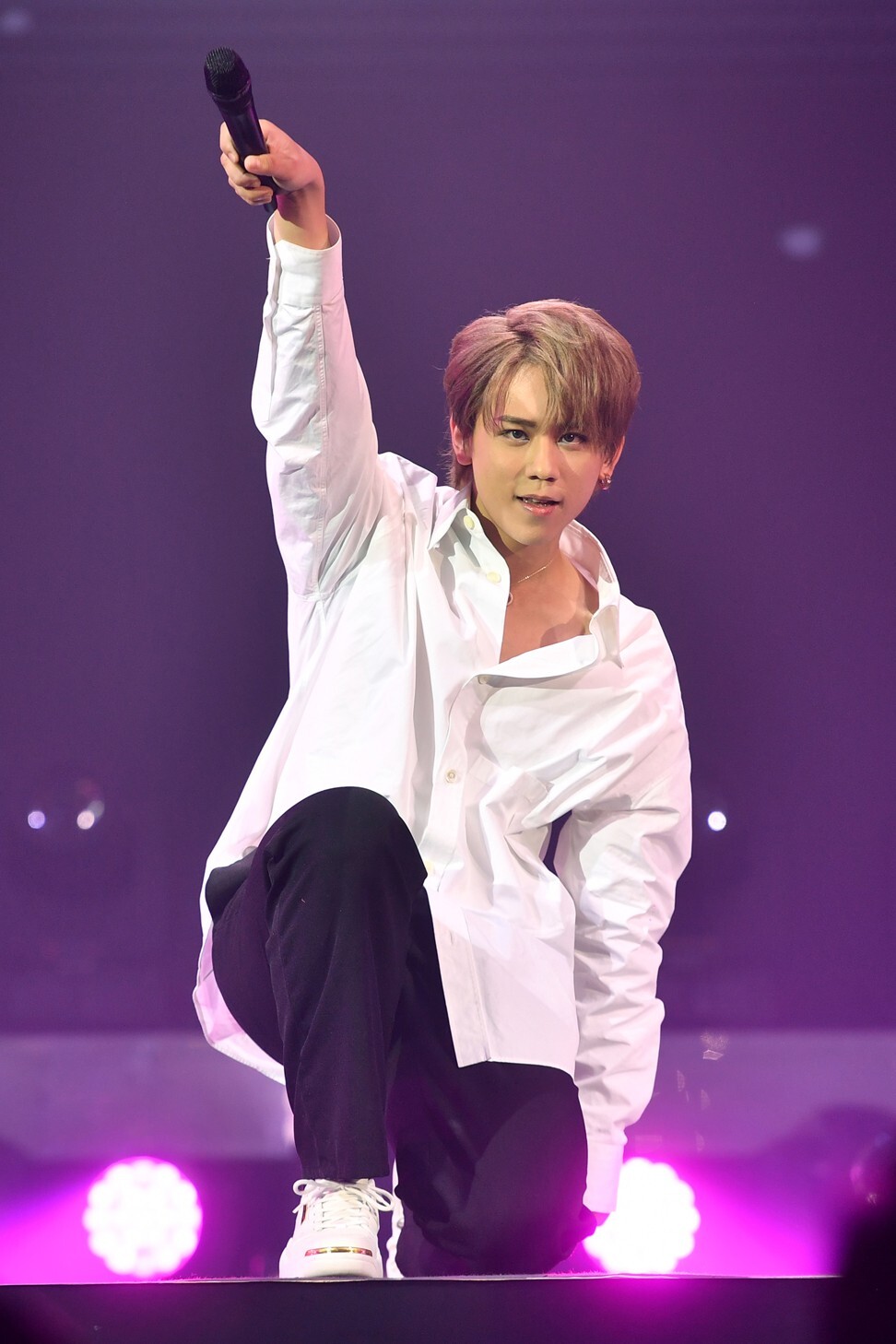

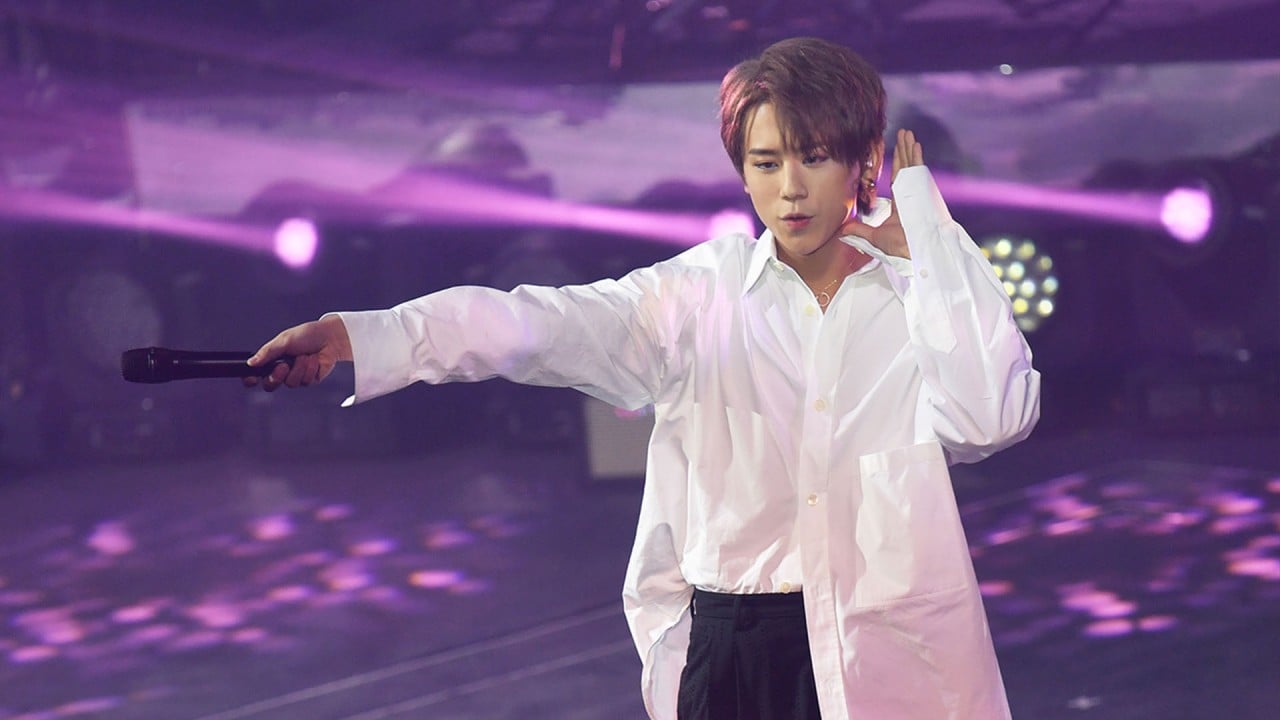

Forget K-pop: why Hong Kong Canto-pop singers like Keung To, Serrini offer hope in a city weary of Covid-19 pandemic and politics

- Singers such as Keung To are being supported by youngsters beset with deep angst over their future and fears that their identity is under threat

- As Hong Kong gradually opens up to live shows with the pandemic under control, residents grab the opportunity to soak up positivity

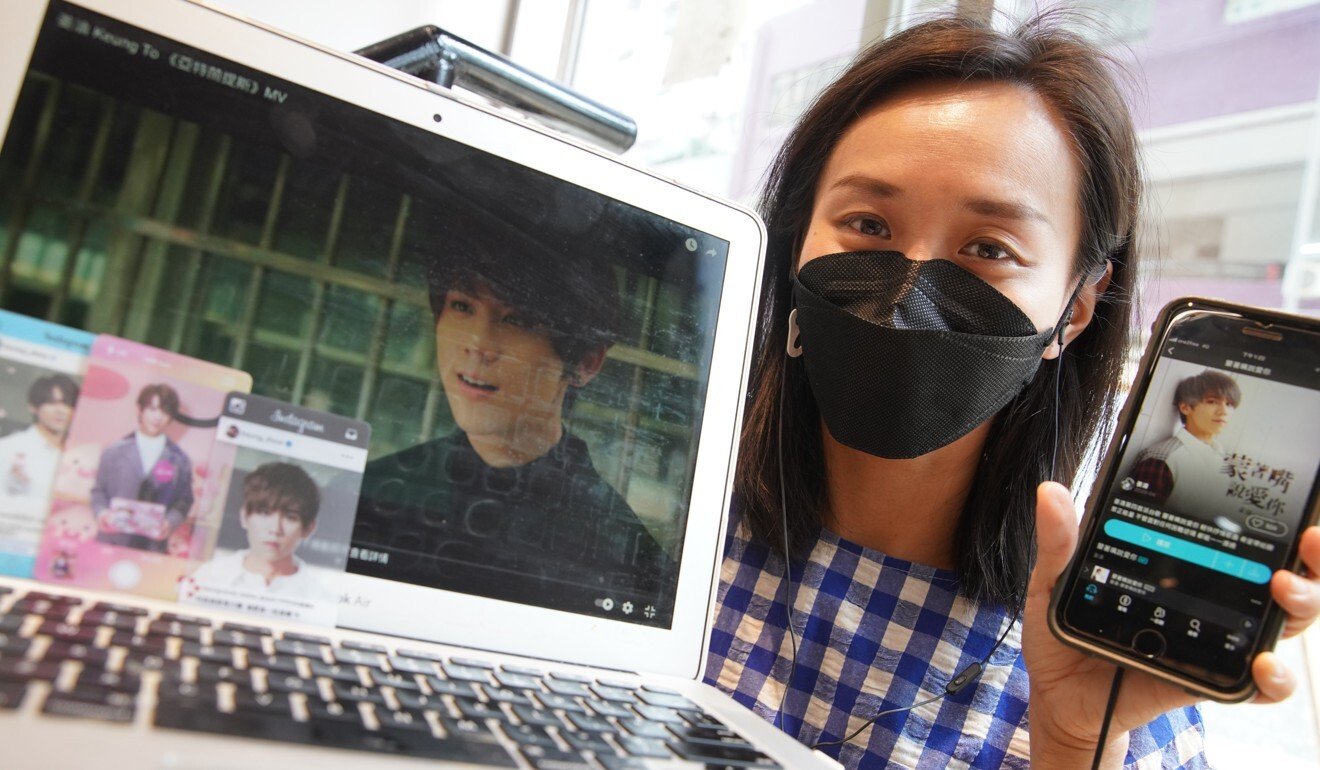

Evelyn Char Ying-lam was walking through the heart of Hong Kong’s shopping district in Causeway Bay late last month when an advert on the side of a tram caught her eye and made her stop in her tracks.

It was a promotion marking the 22nd birthday of her favourite Canto-pop singer, Keung To. Similar ones were plastered at spots around the city, many of them designed and paid for by the fans themselves.

Char, 35, chased after the tram, her long white dress snapping in the wind, until it came to a stop and she could finally take pictures.

That night, she joined hundreds of other fans on a nearby street to celebrate the occasion, exchanging cards and stickers featuring Keung. But the gathering was also a chance to revel in an emotion that for Char, an art critic, had been in short supply lately in the city – a sense of belonging.

I believe Hong Kong singers can definitely become Asia’s top again

Home-made idols

Keung is perhaps the best known member of a new wave of Canto-pop artists being passionately supported by members of the younger generation at a time when many are beset with deep angst over their future and fears that their identity as Hongkongers is under threat.

05:10

Hong Kong Canto-pop sees revival after 2019 protest and Covid-19 pandemic

For Generation Z, musicians such as Keung represent a new breed – eminently relatable and worlds apart from their predecessors and even contemporaries who are viewed as pre-packaged, and in the case of some, overly beholden to mainland China.

And while the rise of social media and streaming technology allows these indie artists to connect with fans in a music scene dominated by the global juggernaut that is K-pop, the question remains whether they can find an audience beyond Hong Kong, and how that success will affect their appeal as icons of strong local identity.

Even the way Keung first came to public attention is testament to his appeal as an alternative icon.

Yan Chan, an 18-year-old student who counts herself as one of his earliest fans, recalls watching Keung competing on local channel ViuTV’s reality talent contest King Maker in 2018. He was among 12 contestants who ended up stealing the show and went on to form the boy band Mirror that year.

Following its launch in 2016, the ViuTV show has managed to capture a sizeable portion of younger viewers who eschew the more established TVB, a broadcaster that for decades has been the platform of choice for stars to beam their way into Hong Kong households.

Not only was TVB seen as their “parents’ channel”, but the broadcaster was accused of siding with the government in its coverage of the social unrest.

As other local media come under increasing pressure from Beijing to reflect the official line, ViuTV’s focus on self-produced live entertainment seems increasingly to be resonating with the younger demographic.

Chan estimated that about 60 to 70 per cent of her friends who were mostly fans of K-pop just a few years ago were now starting to listen more to local acts.

“They used to ask me who Keung was, and would say ‘he’s just a Hong Kong star’,” she said. “Now, my friends also like Mirror.”

Keung further cemented his broad appeal in January when he became the youngest person to win two coveted local prizes – My Favourite Male Singer and My Favourite Song – at Commercial Radio’s Ultimate Song Chart Awards Presentation.

He stole the spotlight again at ViuTV’s music awards last month, where he scooped up two prizes for himself and another two for Mirror, declaring: “I believe Hong Kong singers can definitely become Asia’s top again.”

New wave, new appeal

According to Professor Anthony Fung Ying-him of Chinese University’s school of journalism and communication, the new wave of pop culture reflects a diversification of identity as people sought out their own types of music.

But unlike other Canto-pop stars cast as images of icy perfection, the appeal of the emerging artists also rested in part on their accessibility – they came across as ordinary people not so different from their fans, he said.

Many young local fans have abandoned superstars whom they deemed beholden to the mainland market.

Fung noted that one of the challenges ahead was how rising artists could turn their popularity into sustainable commercial success. Whereas the previous approach relied on packaging idols for mass consumption, the budding artists would have to find a way to leverage the existing support base, he suggested.

“The success of this model depends on whether the community size can be scalable to reach a certain size and cross the border,” Fung said.

It’s about people feeling there should be more choices and that associates with the idea of more choices in politics and society

Dr Chan Ka-ming, a social sciences lecturer at Hang Seng University of Hong Kong, pointed to multiple factors behind the new wave of Canto-pop.

Chan said the support Mirror enjoyed was related to the disapproval some people in society had voiced over TVB’s dominance in defining the cultural landscape. Young people did not want their taste to be moulded, he argued. But the shift was about more than simple opposition to the monolithic TVB.

“It’s about people feeling there should be more choices and that associates with the idea of more choices in politics and society,” he said. “ViuTV seems to have created heroes out of this moment.”

The King Maker programme which ran for about 60 episodes, gave the audience a chance to witness the gradual improvement of the contestants, progressing on the basis of talent towards a victory not already ordained by producers.

04:23

Hong Kong’s independent musician Serrini reflects on her growing popularity

While the show’s judging panel played a significant role in deciding the fates of the contestants, viewers also voted on the winners in the final round. That type of autonomy carried a symbolic meaning in Hong Kong’s political climate, Chan said.

Former history teacher Owen Yiu, 24, became a Mirror fan after the contest. While he initially did not think highly of them, he was eventually won over by their dedication to pursuing their dreams, an ambition his generation could identify with, he said.

“Everyone likes to see beginners slowly growing and improving, and it seems more important to us now,” he said.

Lecturer Chan said the degree of success of other rising artists such as independent songwriters Terence Lam and Serruria Leung Ka-yan, popularly known as Serrini, rested on their ability to capture a niche style, which in an increasingly stratified market, resonated with certain fans.

Now, if your work is nice, then I can like you

Discerning audiences

Serrini told the Post that audiences might have grown more discerning in their taste and no longer wanted to blindly follow icons.

In 2012, she was recording folk songs in her bedroom, occasionally performing for small groups. But over the past few years, she has grown in popularity as she fleshed out her style and won a silver award in the female singer of the year category at ViuTV’s latest music awards. Her hits include Internet Security Threat, Kowloon Blondie Ling and Don’t Text Him.

She believed fans gravitated towards her songs because they included colloquial Cantonese lines, referenced local landmarks and used hybrid cultural elements.

Serrini said she used to joke about how artists such as her would not have found a following before, but audiences were becoming more accepting of feminism and diversity.

She agreed with Chan that today’s music industry offered wider choice and was able to cater to more specific tastes.

“No one can be ‘the one’ now,” she said. “There used to be the ones, like the bigger names. But now, if your work is nice, then I can like you.”

Serrini noted that budding singers could more easily upload their songs to streaming platforms without the involvement of big labels, while cheaper and better production was proving a boon for younger artists. But she also admitted the pandemic played a role in her popularity.

“People can’t really travel a lot,” she noted. “They need something interesting right? And we are interesting, so they just come and see us. We’re like tourist attractions locally.”

The live experience

Emotionally charged concerts have long been a staple of the local music scene and their absence for much of the pandemic has been keenly felt. The return of shows offered temporary respite from the constant stream of news not just about the Covid-19 health crisis but also the political challenges the city faced, fans said.

Under social-distancing rules, performance venues are restricted to operating at a maximum of 75 per cent of capacity with at most four consecutive seats available for the audience in the same row.

Some singers have been expressing positive messages in their concerts with such phrases as “have faith” and “add oil”, a Cantonese expression meant to show encouragement and widely heard throughout the social unrest.

Julian Ng, 28, who works in public relations, attended one of Serrini’s concerts last month and described the experience as like watching a friend.

The performance cheered him up and allowed him, if only briefly, to forget about the developments in Hong Kong that worried him, such as the arrest of 47 opposition members on suspicion of breaking the national security law over their roles in an unofficial primary election last year.

“It’s like joining a cult,” he said. “She sprayed water towards her fans as if the bottle she was holding was holy water. It was crazy.”

When he sat down in the Hong Kong Coliseum in Hung Hom for a concert by RubberBand, which first appeared on the scene in 2004, he felt the musicians and audience members were creating an atmosphere not unlike the anti-government protests. Some audience members held out five fingers, reflecting the anti-government movement’s call for “five demands, not one less”.

“I felt very warm that everyone is still here,” he said.

Similar sentiments were echoed over the following days in social media posts about the concert, with many attendees expressing thanks to the home-grown band for the night.

Chan from Hang Seng University said some residents might turn to pop culture to seek reassurances at a time when they could not express their views publicly.

“Pop culture is always political,” he said, pointing to cultural studies in Britain and the United States that argued while certain creative works were not meant to be political, their reception could often be.

Solace in songs

But she found solace in Mirror songs such as Warrior a passionate appeal to fight for a new order with encouraging lyrics such as “with faith, ordinary people can also fly”.

“It’s about new voices and a new revolution in the music industry. But the same messages can also be read in the context of what is happening in our society,” she said.

The final line of Warrior, sung in English, is: “Never give up, I got it, I’ve got a warrior heart”.

And she appreciated that her idols did not steer clear of certain controversial phrases and topics as more established stars had done.

“When bad things happen every day, watching the music video of Warrior and listening to the song gives me energy to carry on and not to give up yet,” she said.

She felt the rise of Mirror’s popularity reflected a wider hunger to strengthen Hong Kong’s cultural identity.

“The difficulties facing the city are not new,” she said. “No matter how bad the environment or how long we have failed to fight for something, we keep trying and never give up.”

Additional reporting by Jeffie Lam

Illustration: Lau Ka-kuen