Defender of freedoms or defiler of national sovereignty? What exactly was Hong Kong’s Apple Daily?

- Critics loathed its sensationalist, pro-opposition and anti-China slant, its supporters loved its fearless reporting against those in power

- But after 26 years of bucking the system, the tabloid-style newspaper’s foes have had the final say

Is Apple Daily more than a newspaper?

Critics loathed its sensationalist, pro-opposition and anti-China slant. But loyal readers loved its fearless reporting against those in power, and advancing its own understanding of what democracy ought to look like – unfettered and unbound by Beijing.

Yet, there was a rare consensus among both sides: Apple Daily was much more than a newspaper. To its fans, it was a defender of freedoms. To its foes, it was the defiler of national sovereignty.

After 26 years of unrelentingly going after the local and central governments, the final body blow to the paper came last week when police arrested its editor-in-chief, publisher and three other executives for more than 30 reports allegedly calling for foreign sanctions, a violation of the national security law.

01:36

Hong Kong leader Carrie Lam says Apple Daily raid was not attack on press freedom

With the freeze on all its assets and those of Lai’s holdings – he was their biggest lender – the paper folded within days of the latest arrests.

Secretary for Security John Lee Ka-chiu said the arrests were not to target the press but to go after a publication that used “news coverage as a tool” to harm national security.

“No one should use new reporting as a disguise or safe haven to endanger national security. The government will use all legal measures to prevent, interdict, and suppress such activities,” Lee said, as he warned all journalists to stay away from the so-called criminal elements who had been detained.

Hong Kong’s forbidden fruit and the national security law: the rise and fall of Apple Daily and founder Jimmy Lai

Lee’s view on how Apple Daily was just a cover to endanger national security and a campaign against China will be tested when the case goes before the courts.

For now, the court of public opinion appeared to mourn the death of a paper, analysts said. From today, Hong Kong would for the first time since 1995 be without the colourful, feisty institution that, in pushing the boundaries of what could be reported, enlarged the space for other media outfits, they said.

In many ways, it appealed to the insecurities of the average Hongkonger restless of the control of the central government and was an outlet for their frustrations, senior journalism lecturer Bruce Lui Ping-kuen of Baptist University said.

“It was indeed not just a newspaper or a media outlet,” he said. “It was a symbolic organisation, and a thermometer of ‘one country, two systems’, demonstrating the central government’s tolerance of the differences between the ‘two systems’.”

Chinese University political scientist Ivan Choy Chi-keung said its closure marked “the end of an era” when authorities had to swallow some of the harshest attacks from the bad boy of the local media.

“Its popularity stemmed from the anxiety among certain quarters in Hong Kong about the city’s situation under one country, two systems, said the academic, citing the paper’s early days when it was founded in 1995, just two years ahead of Hong Kong’s return to China from British colonial rule.

But pro-establishment lawmaker Regina Ip Lau Suk-yee had a different view: “Apple had some entertaining features, but since its establishment, the owners and editors had weaponised the newspaper to incite disaffection and hatred.”

Since its beginnings, the paper, known for its sensational reporting style, had been no stranger to controversy. It stepped into a storm of accusations of chequebook journalism in its early days in what was notoriously known as the “Chan Kin-hong saga” in 1998. It paid a philandering widower, whose wife and two children had just plunged to their deaths, to pose in bed with two women.

Lights out at Apple Daily: Hongkongers queue for hours to buy newspaper’s final issue

Choy said the paper, infamous for sending paparazzi to stalk celebrities and politicians, changed the media landscape in Hong Kong.

“Before Apple Daily was founded in 1995, media organisations generally adopted a cooperative attitude towards the government,” he said. “The newspaper has won the hearts of local readers who distrust those in power and are apprehensive about Hong Kong’s return to the Chinese rule after 1997.”

In its editorial in the inaugural issue on June 20, 1995, titled “We belong to Hong Kong”, Apple Daily vowed to run “a newspaper for Hong Kong people”.

On July 1, 2003, the newspaper published giveaway protest posters and a set of stickers before a rally attended by half a million people opposing the controversial national security legislation.

The poster read “Don’t want Tung Chee-hwa”, calling for the then chief executive to step down. The protest posters became a smash at the historic march, which eventually forced the Hong Kong government to shelve the bill to implement Article 23 of the Basic Law, the city’s mini-constitution.

01:31

Crowds gather outside court in support of Apple Daily executives on national security charge

Ip, who was secretary for security at the time and in charge of pushing for the legislation, accused the newspaper of unfairly targeting her then. “It demonised Article 23 and me,” she said, adding that the coverage actually called for people to join the rally.

In 2000, the newspaper also accused her of likening the local press to pigs, even though she said she was using the mammal characters in English writer George Orwell’s fiction Animal Farm to demonstrate how media depicted certain matters.

Apple Daily was known for its unequivocal support of the Occupy protests in 2014 that paralysed parts of the financial hub and the protests against the now-withdrawn extradition bill in 2019, distributing posters and other paraphernalia.

“Like it or not, it was more than an ordinary newspaper,” Choy said.

You can call it advocacy journalism, but it is undeniable that Apple Daily is a newspaper with distinct characteristics

Paul Lee Siu-nam, professor with Hang Seng University’s school of communication, described it as a “partisan newspaper” adopting strong stances on issues such as democracy and human rights.

“You can call it advocacy journalism, but it is undeniable that Apple Daily is a newspaper with distinct characteristics,” Lee said.

“For its supporters, the newspaper is speaking out and looking out for them,” he said, adding not many local media organisations adopted nearly as critical a stance on the government as Apple Daily did.

In 2000, the newspaper’s expose of former legislator Gary Cheng Kai-nam’s alleged abuse of public office led to the downfall of the once flamboyant political star. He had to give up his seat for Hong Kong Island, resulting in a by-election. A year later, the former vice-chairman of the Democratic Alliance for Betterment of Hong Kong (DAB) was jailed for 18 months for corruption and deception.

In March 2003, the tabloid first reported that then financial secretary Antony Leung Kam-chung had bought a new Lexus just weeks before announcing tax increases for vehicle registration in his budget. The disclosure sparked a public outcry and Leung resigned four months later.

The newspaper’s explicit support for the opposition camp had long irritated the pro-establishment media, loyalists and Beijing’s organs themselves.

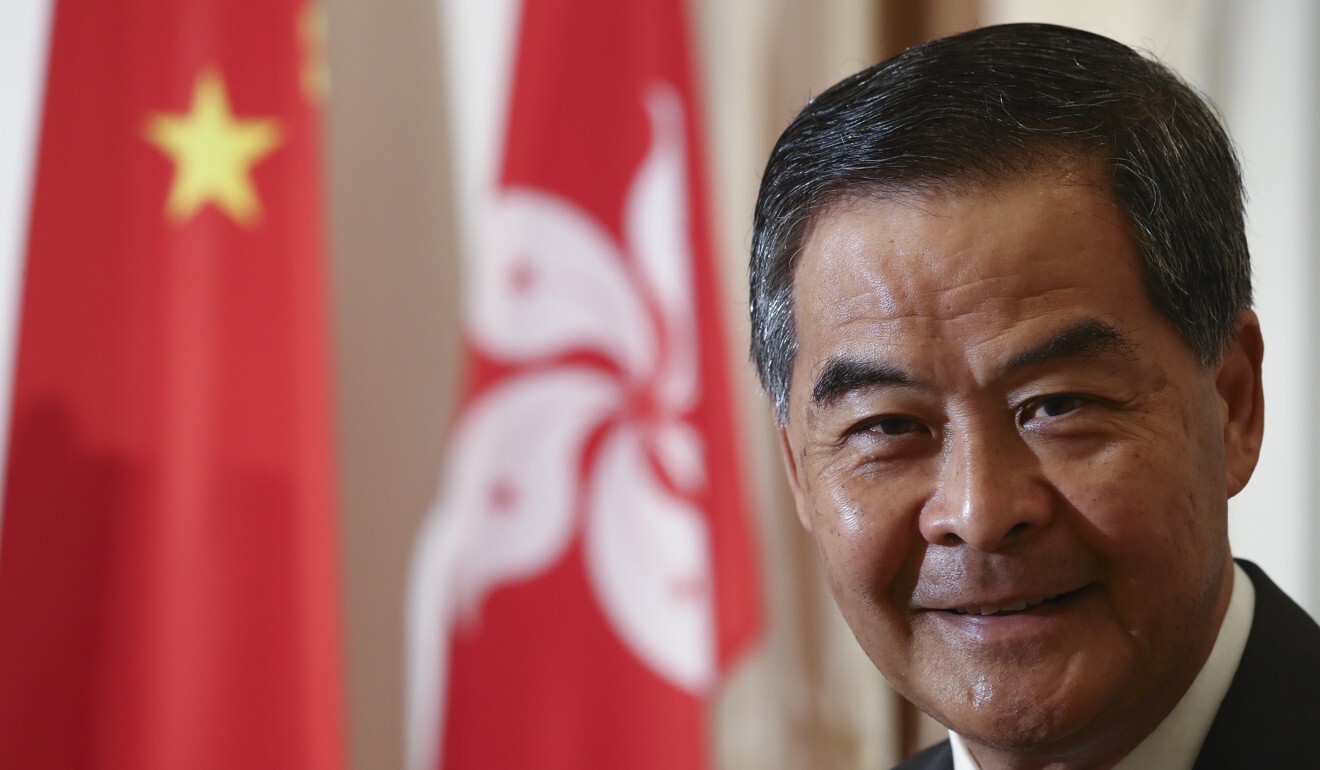

In 2019, former Hong Kong leader Leung Chun-ying, one of the staunchest Apple Daily critics, mounted a Facebook campaign against the paper by “naming and shaming” companies that had placed advertisements in the publication.

On Wednesday, he pressed on. “Apple Daily and Next Magazine, founded by Jimmy Lai, are not media organisations but his political venting tools. Whatever happened to him, his family and assistants had nothing to do with journalistic work or press freedom,” Leung wrote on his Facebook page, adding what they faced were the consequences of someone colluding with “scum from other countries”.

Sex, gossip and free fruit: Apple Daily’s launch in 1995

Peter Kwan Wai, associate dean of Chu Hai College of Higher Education’s Department of Journalism and Communication, said Lai crossed the line of no return when he took a leading role in the anti-government protests of 2019.

Kwan said his actions were a dramatic step-up from being one of the chief cheerleaders, if not orchestrators, of the 2014 Occupy protests.

“This is inappropriate for the owner of a media organisation,” he said of the newspaper’s constant encouragement for people to attend protests, including even providing material for them to hold up, and cut-out masks to wear to demonstrations.

Kwan said he agreed with the government that Apple Daily had gone well beyond its role of being a newspaper.

But Francis Lee Lap-fung, director of Chinese University of Hong Kong’s school of journalism and communication, said disapproving of the newspaper’s approach was one thing, criminalising it was another.

“You can’t shut it down just because you think it’s selling sensational news,” he said.

He added even if there were critical articles or occasional commentaries which called for foreign governments to act in a certain way, targeting a publication for that “would still be undesirable based on the traditional views that give protection to freedom of speech”.

Rose Luweiluqi, a journalism lecturer at Baptist University said Apple Daily had in the past given people an impression that it was biased.

But the final judgment of whether it should continue to exist should have been left to the market. “If its reputation and credibility fell, readers would decide,” she said.