National security law: welcome mats by Britain, Australia, Canada lure thousands who feel Hong Kong is no longer home

- Families, young people, professionals among those leaving because of worries over city’s future; take out pensions

- Some staying put, take wait-and-see approach and others, especially businesses, say city calmer, more stable

This is the final of a four-part series on the impact of the national security law, one year after it was imposed on Hong Kong by Beijing on June 30, 2020. Lilian Cheng and Denise Tsang speak to Hongkongers making plans to leave the city even as businesses and others say they welcome the return to stability to get on with their lives. Read part one here, part two here and part three here .

Hongkonger Andy Wong, his wife and teenage son have never visited Britain and speak very limited English, but they are preparing to start a new life there later this year.

The 54-year-old Hospital Authority clerk, who earns about HK$25,000 (US$3,200) a month, and his wife Sue, 53, a health care worker with a similar salary, made up their minds to leave last month.

They plan to quit their jobs, take their 16-year-old out of school and go with their savings of about HK$400,000 and HK$3 million in pensions.

A year under the national security law: arrests, sanctions, and a swifter Legco

“Nowadays we don’t even have any right of assembly. I cannot see any future here for my son and also for ourselves,” Wong said.

“Now that Britain has opened its doors to Hongkongers, we want to grasp this opportunity to give our son a better future. I am afraid that if we don’t go this year, we may not be able to go in future.”

The family is among tens of thousands of Hongkongers taking advantage of relaxed migration policies introduced by Britain, Australia and Canada, among others, as Beijing tightened its grip over the city.

No official statistics are available, but anecdotal evidence, visa applications as well as the withdrawal of children from Hong Kong schools suggest the number of residents leaving the city is on a palpable rise.

Hong Kong academics quit op-ed columns, cite national security law

“It seems the authorities can arrest and prosecute anyone in the name of national security,” he said, lamenting what he called the vague extent of the sweeping legislation.

Is Hong Kong’s national security law being weaponised?

Dr Cheung Chor-yung, a political scientist at City University, said that in the 1990s, it was mostly the well-off professional elite who left because they were unsure what lay ahead once Hong Kong returned to China.

More than 500,000 people quit Hong Kong between 1987 and 1996, according to government estimates, but about 120,000 returned from around 1997, after obtaining permanent residence elsewhere.

06:15

BN(O) passport holders flee Hong Kong for new life in the UK, fearing Beijing’s tightening control

Cheung said the newly relaxed immigration policies of Western countries targeting Hongkongers appeared to have encouraged a large number of families who might never have considered emigrating before to uproot.

“This is quite different from the two previous migration waves, when only the elites or professionals had the means to move,” he said.

“Hongkongers who left in the past were mainly uncertain about the future but this time, they have already lost hope. Now people are leaving because they are certain about the impact of Beijing’s national security law on freedom or the next generation.”

Explainer: BN(O) ticket to Britain: not everyone can walk in, and it’s not free

But on all these fronts, Hong Kong still had much to offer, he said, citing various economic data.

“We are convinced Hong Kong’s institutional strengths and core competences remain strong,” he told the Post.

Welcome mat of the West

Among countries that condemned Beijing’s increasing control over Hong Kong, Britain responded by opening a new pathway to immigration for people from its former colony.

The new rules allow Hong Kong residents who have graduated from a Canadian university in the past five years to apply to work there for up to three years. Those with equivalent foreign qualifications are eligible too.

Canada is also offering permanent residence to eligible Hongkongers already working or recent graduates still there.

Britain to open up housing support for poverty-stricken Hong Kong BN(O) holders

Data from the MPF Schemes Authority showed there were 8,100 withdrawals – a total of HK$1.7 billion – on the grounds of permanent departure from Hong Kong from July to September last year alone, up from the quarterly average of 6,000 from April to June before the security law was passed, with a total of HK$990 million.

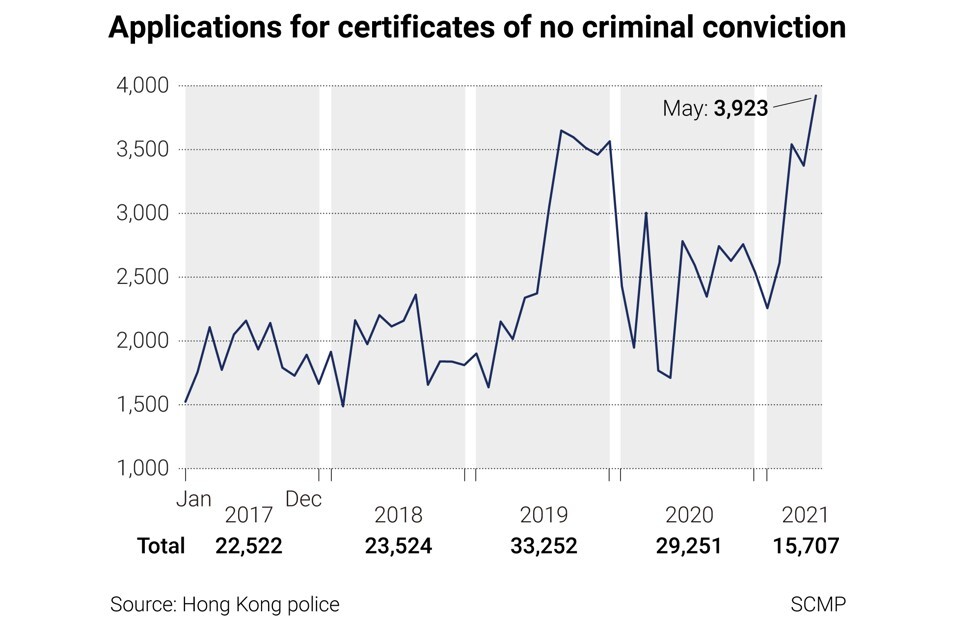

Another sign of the restlessness can be seen from applications to Hong Kong police for certificates of no criminal record – a prerequisite for some immigration programmes – which reached about 15,700 in the first five months of this year, 67 per cent of the figure for the whole of 2018 which had 23,500 cases. In May alone, there were 3,923 applications, a high since 2017.

But not everyone making such applications will leave immediately. Some take a wait-and-see approach.

Jacky Tse, 36, had planned to emigrate to Australia with his wife and two-year-old son soon after the national security law kicked in last June. He studied the criteria set by different countries at length.

“We were also concerned whether we could find a job in Australia, thus recently, our family was in discussion on whether we should move to the United Kingdom instead when the situation improves.”

For the Tse household, deciding to uproot remains a tough decision they are still mulling over. “It could be a no-return journey,” Tse said.

Yet for other families, the children’s future seems to be their singular focus, forcing them to put aside all other considerations.

05:50

What you should know about China's new national security law for Hong Kong

Surveys by teachers’ unions have found a trend of pupils withdrawing from school over the past year.

The number added up to at least about 2,000 in a survey by the Professional Teachers’ Union in May, when a quarter of 183 schools polled said more than 20 of their pupils had left since September last year.

A Post analysis of Education Bureau statistics showed that roughly 19,300 pupils – about 3 per cent of the student population – dropped out from local and international primary and secondary schools in 2020-21, nearly double the 10,400 who did so the previous year.

Over 400 Hongkongers seeking asylum abroad since 2019 protests

Around 5,280 withdrew from private and international schools, compared with about 2,580 the year before, while 14,000 students quit local schools in 2020-21, up from 7,800 in the 2019-20 school year.

University students are also believed to be among those who have dropped out, presumably to continue their studies abroad.

Chinese University political scientist Ivan Choy Chi-keung said he had witnessed a lot of families and young people choosing to move abroad in recent months.

“Several students sent me farewell messages in the middle of the semester while others simply quit the university. This has never happened to me in the past 20 years,” he said.

He suggested these students had decided to take advantage of offers by other countries to let them study and gain citizenship there.

“Some of them have simply lost hope in the city’s future,” he said.

Choy said Beijing’s plan might be to allow more mainland Chinese to move to Hong Kong and make up for those leaving, dampening the effect of the departures, but it was hard to tell how many would come.

City University’s Cheung recalled that emigration in the 1990s opened up opportunities for the Hongkongers who chose to remain, especially those in their 40s who saw faster promotions.

“This time, the situation may be very different, as in public or semi-public organisations, political loyalty also plays an important part now,” he said.

Best is yet to come for Hong Kong and nation, says ex-city leader Tung Chee-hwa

Whatever their reason for leaving, Professor Paul Yip Siu-fai, associate dean of the University of Hong Kong’s faculty of social sciences, cautioned people against departing without making a thorough and proper assessment. He said he knew many who experienced depression after a few months of emigration.

“There are often a few stages for the emigrants: first they are excited and happy as they can finally leave the place, but if they do not get into the environment and culture, there could be a long period of depression, with the lack of support and career overseas,” he said.

Yip urged the Hong Kong government to help those left behind, especially the elderly. Its offices abroad should also still engage the emigrants. “At least, show signs of being welcoming if they hope to return to the city one day,” he said.

Fillip or red flag for businesses?

Even as people decide to up stakes because of the law, others say it has been good for the city, at least in restoring calm and order, even if society remained highly polarised.

Exodus unlikely to dent Hong Kong home prices, say analysts

Financial secretary Chan said: “When violent social incidents broke out in 2019, the No 1 concern for many chambers of commerce was when Hong Kong could restore stability.

“There is no doubt that the enactment of the national security law has helped restore social and political stability in Hong Kong, creating a safe and secure environment conducive to business and investment for companies from all over the world.”

Ordinary lives had benefited from the return to stability. He said the financial market had stayed robust and buoyant since the second half of last year, with daily trading of Hong Kong-mainland cross border stocks, capital inflows and bank deposits recording year-on-year growth.

The combined value of Hong Kong-Shenzhen and Hong Kong-Shanghai trading hit an annual peak of about 150 billion yuan (US$23.2 billion) last July, the month after the national security law took effect. The combined northbound trade was 45 per cent higher in the second half of last year than the first half, he noted.

So far, Hong Kong’s business sector has not expressed concern about the impact of the national security law.

A survey of Japanese businesses by Japan’s consulate in Hong Kong found fewer respondents expressing concern about the law in the first three months of this year compared with the preceding quarter.

Nearly 70 per cent of 228 respondents did not find any impact on their business and only 6.4 per cent said there was a negative impact.

A recent survey by the influential American Chamber of Commerce in Hong Kong (AmCham) found that 58 per cent of respondents had no plans to leave the city, even though those polled were uncomfortable with the law.

“That is a huge red flag for many of our companies because among other things that make Hong Kong great is the local talent. Talent must feel comfortable staying here and feel they have a future, too,” she said.

However, Jim Thompson, founder and chairman of Crown Worldwide Group, a major removals firm with about 450 employees, said the national security law had helped to restore much-needed peace and stability.

Youth pessimistic about Hong Kong’s future, almost 60 per cent want to leave

The 81-year-old American, who has lived in the city for 42 years, said: “Hong Kong is not as scary as people say. Nothing is more frightening than the street violence during the social unrest in 2019.”

Crown has seen its removals business to Britain rise about 20 per cent so far in 2021 compared with the last two years, with a slight decrease from people moving into the city.

But Thompson said he believed some of those leaving now would eventually return, just as in the years after 1997.

Expatriates working in Hong Kong appear to have been generally unaffected so far by the impact of the national security law and other political changes.

The Covid-19 pandemic has made a bigger impact on the expatriate community, with the number arriving sharply down, while some of those working in Hong Kong have returned to their countries after losing their jobs in the downturn or to be with their families.

Number of civil servants quitting Hong Kong government hits 15-year high

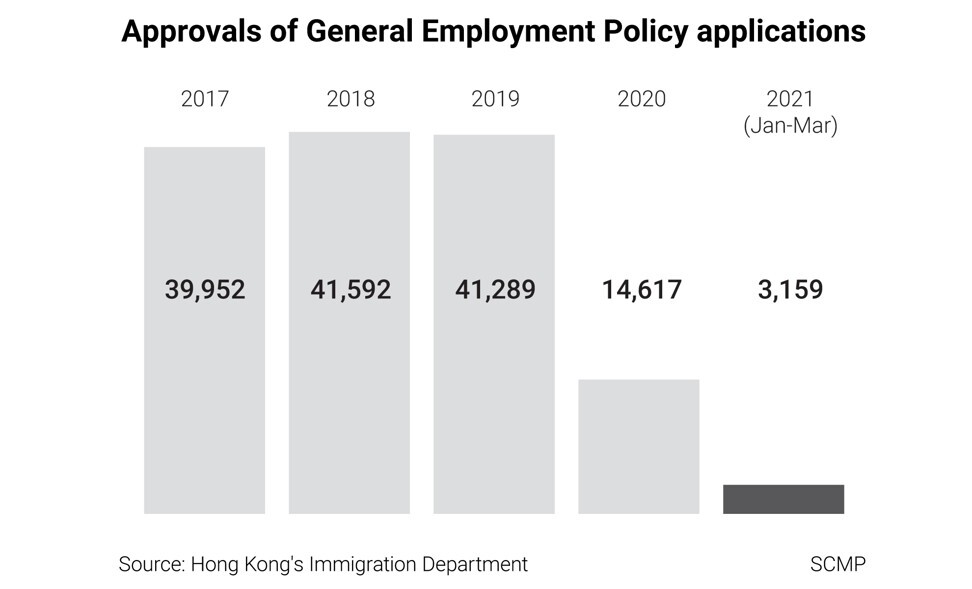

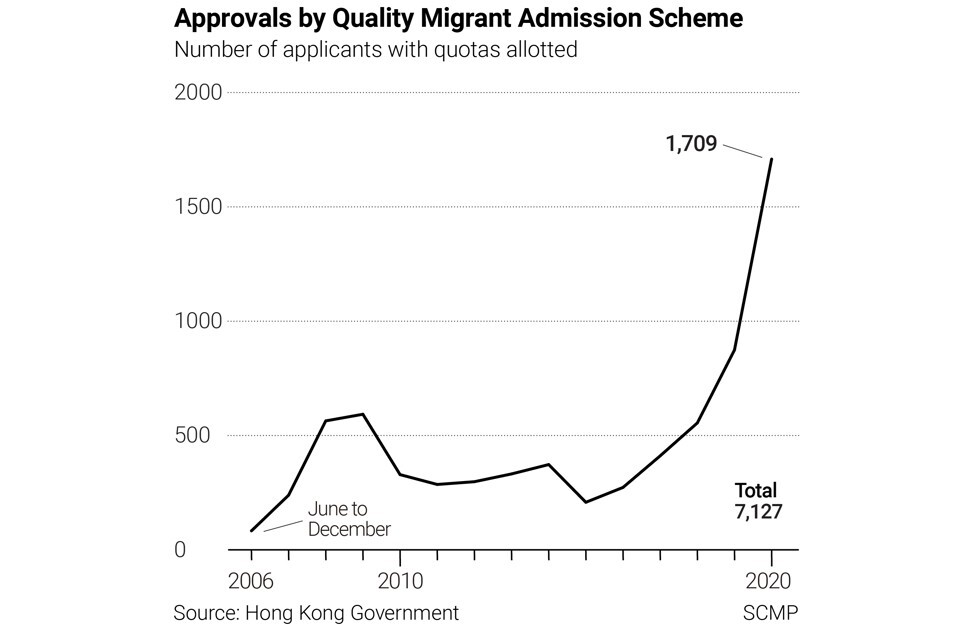

The past year has also seen a drop in the number of outsiders moving into Hong Kong under various migrant and talent admission schemes, with this being attributed mainly to the pandemic which has paralysed international travel since early last year.

There is usually an inflow to the city through the General Employment Policy which excludes mainland Chinese and the admission scheme for mainland talent and professionals.

The number of new employment visas approved fell sharply from 41,289 in 2019 to 14,617 last year for expatriates excluding mainland Chinese and from about 14,053 in 2019 to fewer than 6,995 last year for mainlanders.

The number who extended their stay under both categories declined 12.7 per cent and 16 per cent respectively.

Political scientist Cheung said expatriates everywhere were more likely to worry about their own well-being than the impact of something like the national security law.

“Most may be more concerned about the impact of Covid-19 and whether they might face dismissal or a pay cut, and less concerned about political impacts in a particular city,” he said.

“Overseas companies still see China and Hong Kong as places with more opportunities, compared with European countries that are hard-hit by the economic downturn amid the pandemic.”

Some mainlanders living in the city – the target of protesters fuelling anti-China sentiments – said the law had helped them feel like they could continue living in Hong Kong.

Jack, a 29-year-old banker from Zhejiang province who has lived in the city for the past seven years, is among them.

“But those who used to be outspoken may feel pressure to speak carefully on politically sensitive issues,” he said, adding the legislation did not affect him much as he intended to stay on the safe side of the law.

National security police ‘have list of people to be arrested if they try to flee’

Others said they were less certain. Yo-yo Li, a specialist in visual arts and social media, wondered if her future career prospects might be affected by the government’s tightening scrutiny of films and public broadcaster RTHK after the imposition of the national security law.

“I don’t know where the red line is and am worried about the room for creativity,” Li, in her late 20s, said.

In the expatriate community, there have been similar reverberations, according to old-timers here since before the handover.

Briton Ruth Benny, founder of a Hong Kong-based education consultancy and mother of two, said she knew of at least 20 local and expatriate families who left over the past year, including some who had lived in the city for decades. That was unusual, she added.

She moved her secondary-level children from a Hong Kong international school to a boarding school in Britain, but said it was mainly because the pandemic caused schools in the city to suspend in-person classes for several months last year.

The political changes in Hong Kong had prompted some other families to leave, said Benny, who arrived in 1995 and raised her children in the city, where they were born.

She said they had hoped the “one country, two systems” principle, guaranteeing Hong Kong various freedoms for 50 years after the handover, until 2047, would remain in place.

“Now suddenly, it feels like 2047 came early and the city is no longer what we signed up for,” she said.

Additional reporting by Chan Ho-him and Cannix Yau

Part one of the series looks at protesters and politicians who sought asylum abroad because of the national security law, and how they struggle with so-called survivor’s guilt. In part two, the Post speaks to academics who have stopped writing opinion columns for fear of breaching the law and others who find the areas for research shrinking because of unknown red lines. Part three examines whether the law is being weaponised against political opponents, with the Post speaking to scholars on new precedents being set.