Hong Kong creative industry ‘shrouded in worries and fears’ amid chilling effect of ‘red lines’ under national security law

- Creative community comes to grips with new censorship landscape and complaints from government supporters

- Observers see shades of mainland’s Cultural Revolution as films are blocked, books are targeted

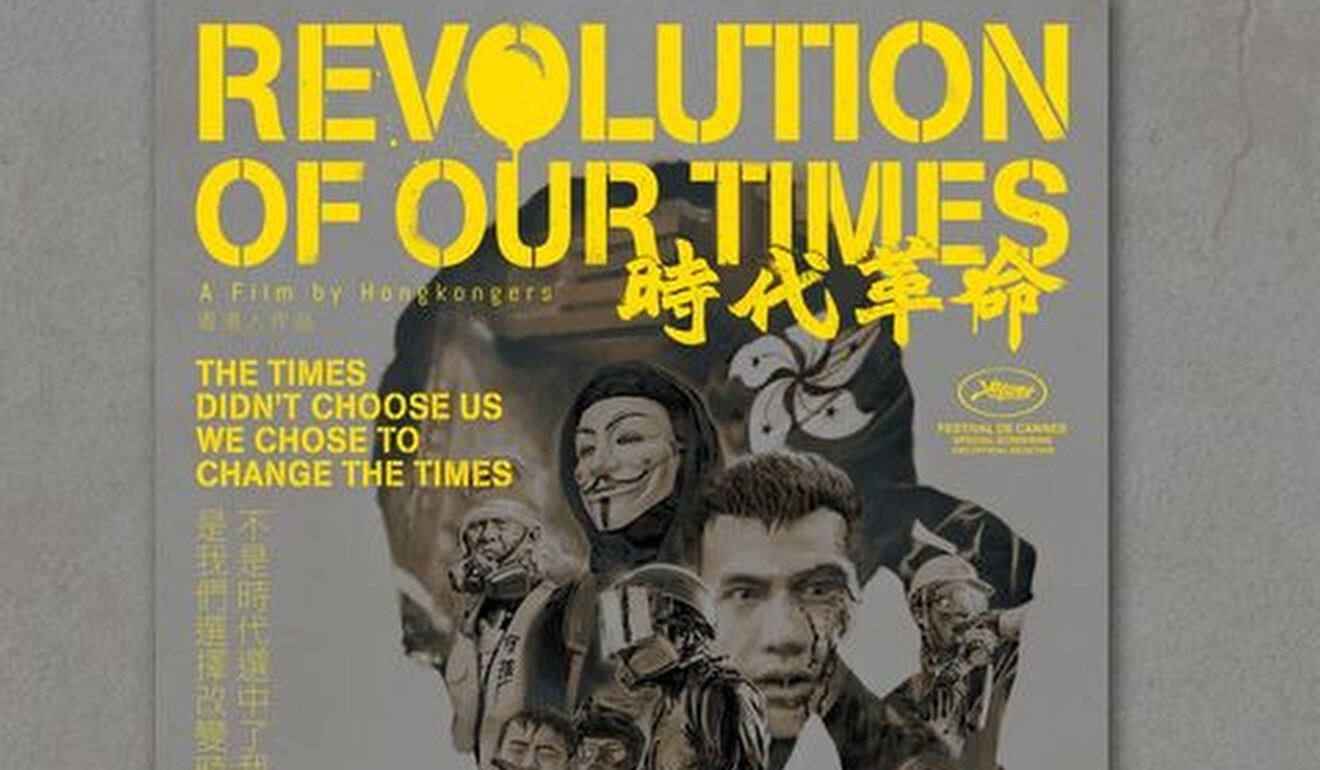

Award-winning Hong Kong director Kiwi Chow Kwun-wai made headlines when his latest documentary was screened at the Cannes Film Festival last month, but the recognition prompted an investor to withdraw from his next film.

The film records how frontline demonstrators operated on the ground during months of unrest that became increasingly violent.

Chow, 42, recalled that his investor was apologetic over pulling out, citing concerns over potential risks.

“Everything is already shrouded in worries and fears. For the safety of others, I won’t screen the film in Hong Kong publicly or even underground in the foreseeable future,” he said.

He was doing so, he said, because he wanted to protect his team, the people interviewed for the film, and those who provided venues to screen it.

Now the city’s creative community, from filmmakers to writers and publishers, say they are experiencing the chilling effect of these changes.

Hong Kong censorship law changes open door to retroactive banning of previous films

Officials and pro-Beijing forces have begun scrutinising their work, with security chief Chris Tang Ping-keung singling out documentaries and books last month, when he said that campaigners for Hong Kong independence had begun using softer forms of resistance.

The government also revised guidelines and authorised censors to ban films believed to have breached the national security law. It proposed on Tuesday legislative changes to pave the way for revoking approvals of previously accepted films.

Some filmmakers have recently stopped showing their work in the city. Others lost venues they had booked. Even those creating non-political content have become extra cautious over crossing the moving “red lines”.

Some insist they intend to carry on despite the tightening grip, but others worry how Hong Kong’s most creative individuals can continue pursuing meaningful art in a rapidly shrinking space.

“If I can’t find investors, I will just keep writing scripts,” Chow said. “When I’m writing a script, I will shut it all out. I will just focus on the story and the characters, I can’t see the red line.”

Hong Kong censors told to ban films breaking national security law

Films neither approved nor rejected

Other filmmakers and distributors have begun feeling the pain of putting out protest films.

On July 2, the Arts Development Council confirmed that it pulled a grant of more than HK$700,000 to Ying E Chi, a non-profit organisation founded by a group of independent filmmakers and the organiser of the Hong Kong Independent Film Festival.

The 88-minute film won the best editing award at the International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam (IDFA), the largest event of its kind in Europe, but council chairman Wilfred Wong Ying-wai said it “beautified riots”.

The fallout came four months after a cinema was pressured to stop screening the film, which was attacked by pro-Beijing media and lawmakers.

Ying E Chi is appealing against the council’s action. Its artistic director, Vincent Chui Wan-shun, said: “I feel it has only listened to some one-sided views.”

Last month, the group was forced to cancel a screening of eight short films after the Office for Film, Newspaper and Article Administration did not issue certificates of approval for two, and did not rule them inappropriate to be shown either.

The office declined to comment when approached by the Post, saying it had already informed the applicants.

Arts body under threat as pro-Beijing forces step up national security law campaign

The two films were White Night, about a Hong Kong girl in exile in Taiwan, and Going Out, about a man who took part in the 2019 protests.

Although six of the films were approved, the screenings had to be called off after the venue operator told the group it was “not suitable” to hold the event there, even though the rent had been paid.

That was not the first time a screening was cancelled. In June, another short film festival could not show Far From Home, a short film about the divided views of different generations on the protests, after the office neither approved nor refused to allow its screening.

National security guidelines for Hong Kong film censors spark industry concerns

On Tuesday, the government doubled down its efforts in tightening its grip on the film sector.

Under a string of proposed amendments to the Film Censorship Ordinance, the chief secretary would be empowered to direct the censorship authority to revoke approvals issued in the past if a particular work went against the interest of national security, according to commerce minister Edward Yau Tang-wah.

Chui said Yau’s comments made it clear their previous screenings had been legal, adding that if authorities reversed decisions on approved films, he would stop showcasing the works.

In July, Chui had said on Facebook that Ying E Chi would continue to promote its films overseas if some could not be shown locally. A screening of Inside the Red Brick Wall is planned for September 11 in London.

The group will host online screenings for other films, and Chui said he was brainstorming ideas for films on Hongkongers emigrating and film censorship.

“We know that boldly confronting something does not work,” he said. “But under this system, we can still cover topics Hongkongers care about that the main film industry does not want to risk.”

Tenky Tin Kai-man, spokesman for the Federation of Hong Kong Filmmakers, predicted there might be no commercial films with themes related to controversial social issues more than a year from now.

Following the revised censorship guidelines issued in June, he said, commercial filmmakers would have to be more cautious and not court trouble.

“Those who have market sense will not attempt something risky, ” he said.

Books that ‘beautify violence’ attacked

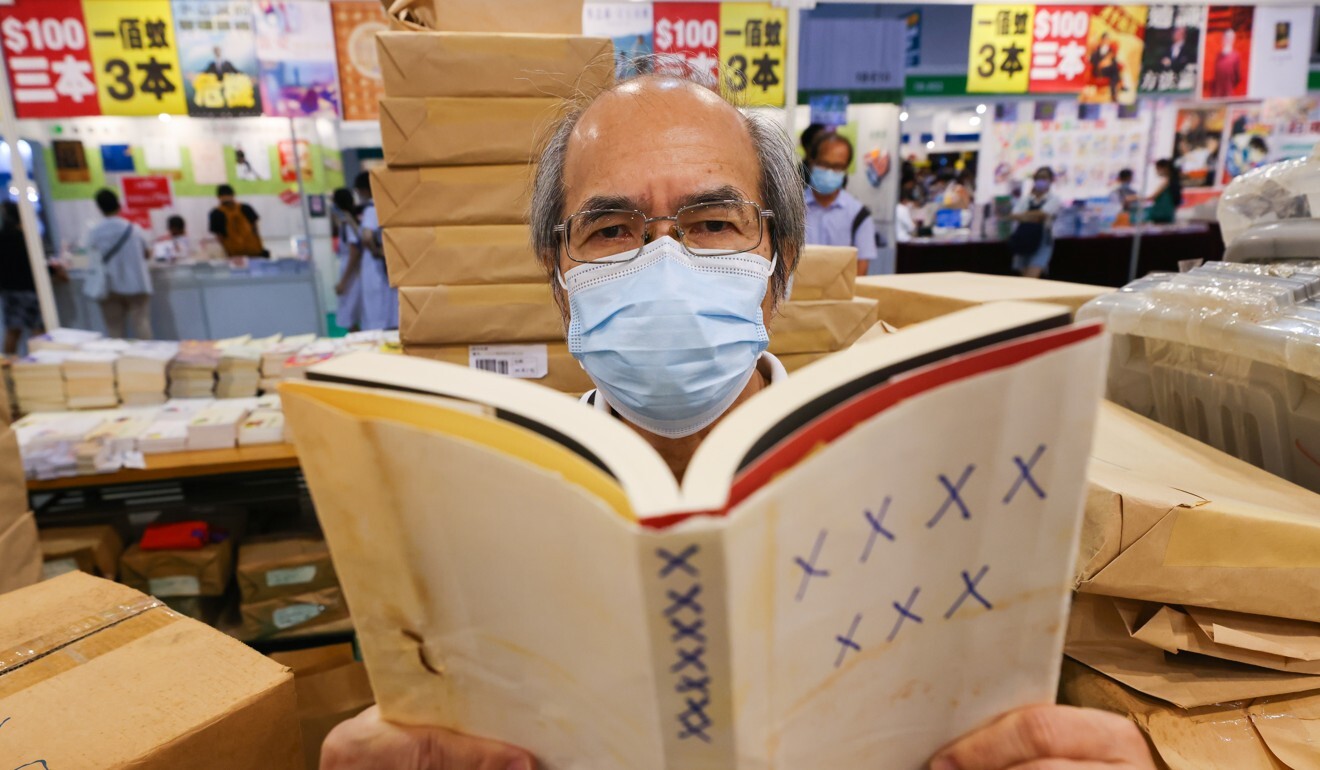

But on the second day, Tang Tak-shing, chairman of the pro-establishment activist group Politihk Social Strategic, complained to the national security authorities about eight books sold by exhibitors Hillway Culture and Kind Of Culture.

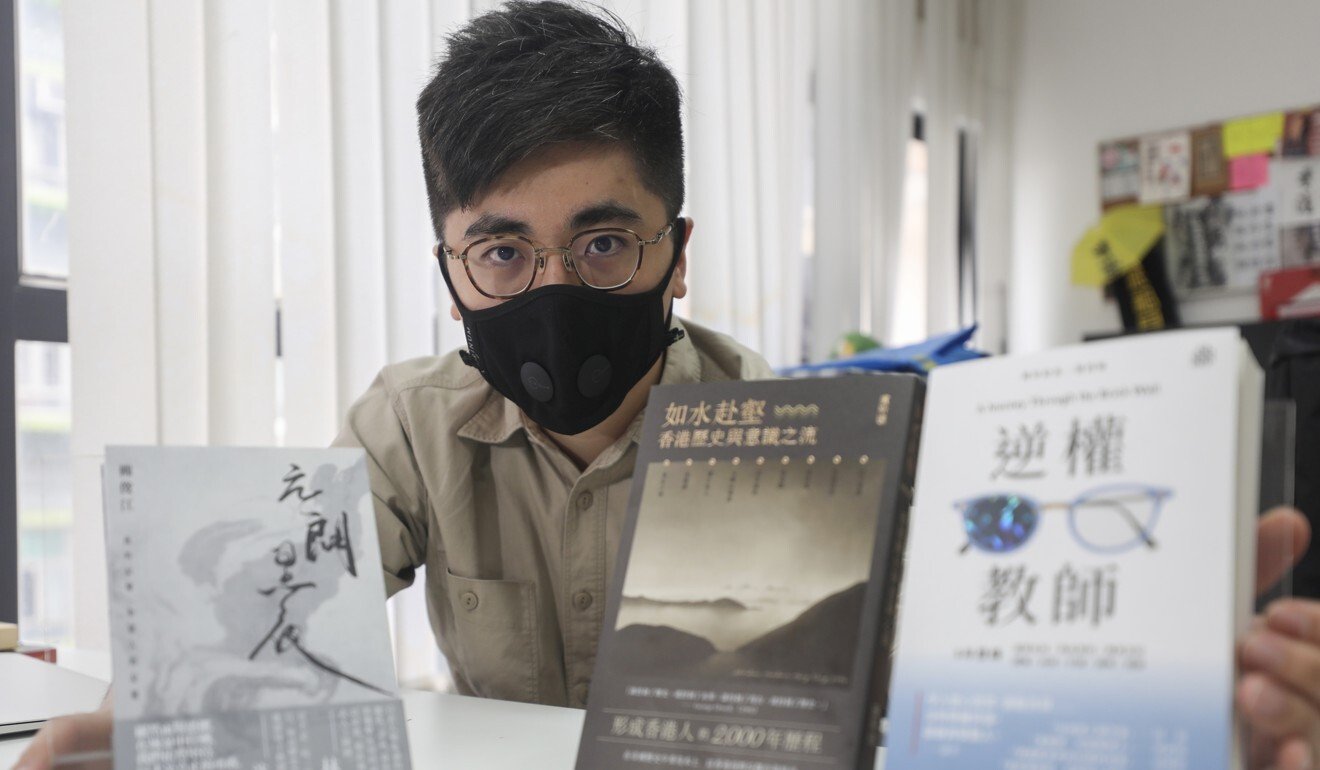

Despite the complaints, both vendors carried on as usual, attracting long queues at times. Some shoppers said they wanted to get their copies early, in case the books were not available in future.

Hillway founder Raymond Yeung Tsz-chun said he expected complaints despite several rounds of vetting by him, the writers and editors, as well as the printers.

He said printers were more cautious and rejected three titles the company tried to publish, including two on political philosophy that he considered “mild”.

The third was on the protests, but Yeung said his team took care to remove strong criticism of the government and police that might not have a factual basis.

He said he monitored the news to stay on top of the latest political trends. After pro-Beijing newspaper Wen Wei Po criticised some books for “beautifying violence”, he knew he would have to be more careful with such topics.

“These are setbacks that further strangle our publishing freedom, but in the current situation, we must protect everyone,” he said.

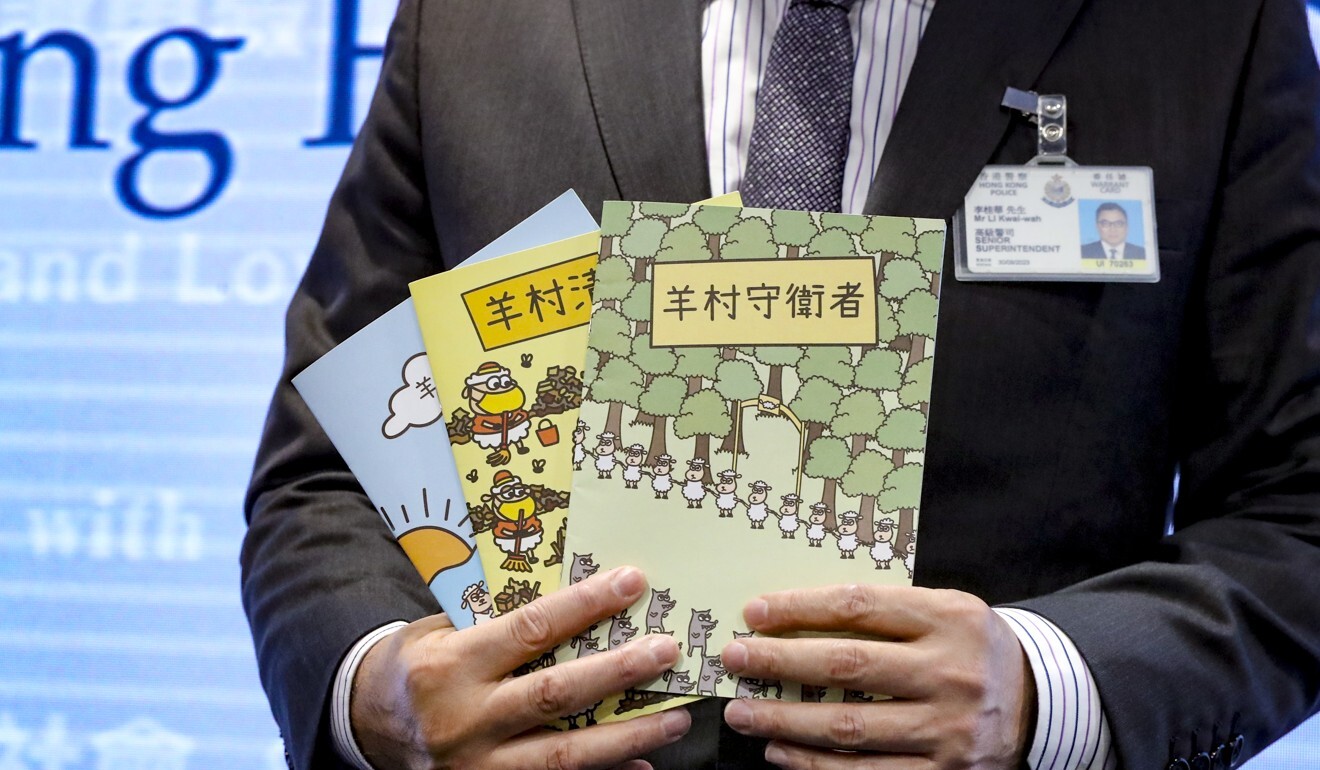

He expected more challenges ahead for his company, after national security police arrested five people over allegedly seditious children’s books.

The three picture books, about sheep defending their village from invading wolves, were published by the General Union of Hong Kong Speech Therapists, one of dozens of groups that emerged amid the protests of 2019.

Senior Superintendent Steve Li Kwai-wah, of the National Security Department, said the group’s aim was to instigate hatred of the Hong Kong government and the administration of justice and incite the use of violence and disobedience of the law.

Yeung said drawing a line between criticism and inciting hatred was very subjective.

Even though it was not about politics and focused instead on issues such as wearing masks, inconsiderate behaviour and vaccination, he was considering making adjustments to avoid offending anyone.

“I fear some people might misunderstand the content or be prejudiced against former reporters, and therefore consider my book to be socially unethical,” he said.

In the absence of an official list of banned books, some schools have removed books on sensitive topics such as Taiwan and those targeted by the pro-Beijing media.

‘Trend of attacks is emerging’

The University of Hong Kong’s John Burns, an emeritus professor of politics and public administration, said authorities had tried to intimidate filmmakers, writers and publishers to ensure that politically incorrect and illegal views did not spread in the new political landscape.

“The [Communist] Party’s short-term goal is that we all self-censor in Hong Kong,” he said. “The long-term goal is that we in Hong Kong see China and the world as the rest of China does.”

While the city’s creative set had no choice but to heed the political red lines imposed by bureaucrats, he said they could still learn to navigate the space left for creative expression.

This required insight, agility and adaptability, just as their counterparts in closed, non-democratic regimes had done before them.

“As we seek to maintain and expand the space, we must use it or lose it,” he said.

Pro-Beijing political commentator Lau Siu-kai, vice-president of the semi-official think tank the Chinese Association of Hong Kong and Macau Studies, said he could understand why some in the cultural sector would worry about crossing the line and become more cautious.

But he expected that any self-censorship stemming from being overly careful would be temporary, and the situation would ease after more court judgments related to the national security law.

He believed it would be impossible to punish those who produced objective analyses and critiques based on facts.

“Many people have criticised the Chinese government’s policies. Did all mainland scholars not dare criticise national policies? The answer is no,” he said.

But he expected self-censorship to remain for action that would incite others to commit sedition or hate the country.

After decades of observing Hong Kong’s political storms, veteran China watcher Johnny Lau Yui-siu stressed the importance of “smart resistance” in navigating turbulent waters.

“The trend of attacks is emerging,” he warned, noting that supporters of the authorities in Hong Kong had begun unleashing verbal and written attacks on whatever they considered unacceptable.

He likened this to events in the early stages of China’s Cultural Revolution, the dark decade from 1966, when scholars, writers and artists were among those who were persecuted on the mainland, with their works destroyed.

In the current political atmosphere, Lau’s own publisher decided to hold back the launch of his new book on the Communist Party and Hong Kong. It covers both the party’s good deeds and questionable practices in the city, including some insider stories.

This is the first time one of his books has been delayed, but he said: “History has taught us that we shouldn’t put our necks next to the knife that others are holding. We can also take it as a strategic retreat.”

Although disappointed, he said it was important for Hong Kong’s creative community to keep going, while looking for new ways to move forward and go further.

“Don’t think it’s dead yet. It’s just finding a new take-off point,” he said.