Hong Kong’s bookshops, losing readers and struggling through economic slump, try to read between ‘red lines’ of national security law

- San Po Kong independent bookshop the latest to close, with owner blaming ‘the state of politics’

- Worrying about national security law, some booksellers wish for clear guidelines on what titles to avoid

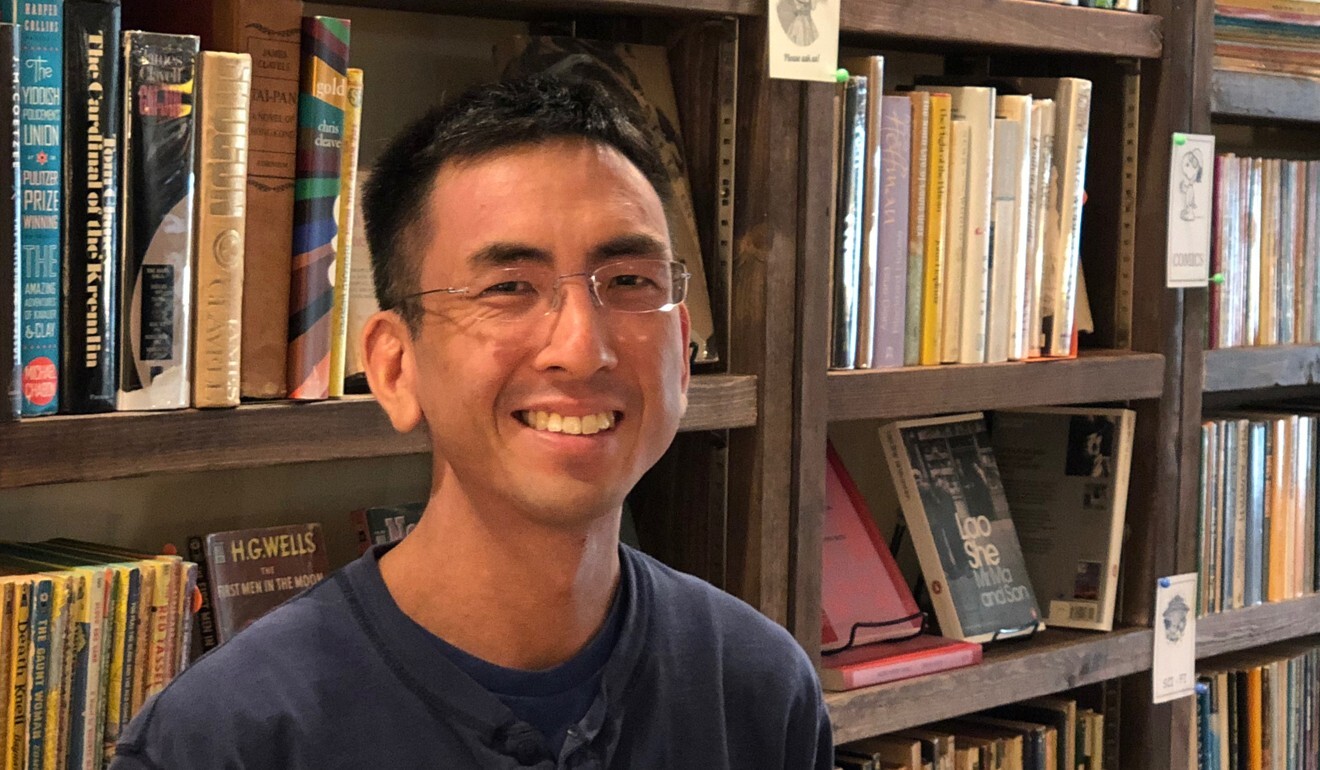

Bleak House Books, a popular independent store in San Po Kong specialising in English titles, announced its closure in August, after four years in business. Its last day will be on Friday.

Owner Albert Wan, a Chinese-American lawyer turned bookseller, blamed politics for his decision to close, and will be leaving the city with his wife and two young children.

“Given the state of politics in Hong Kong, [we] can no longer see a life for ourselves and our children in this city,” he wrote.

Wan also wrote that what he and his family did in their daily lives “was not overtly political”. They have been in Hong Kong for about five years.

The Post contacted Wan to request an interview, but did not get a response.

Declining interest in books and the economic downturn have caused several bookshops to close in recent years, although some have bucked the trend and continued to thrive.

According to the Leisure and Cultural Services Department, people borrowed about 40.5 million books and other materials from public libraries during 2019-20, a drop from 47.8 million in 2018-19, and 61 million in 2005.

Since early last year, at least two independent bookshops and a chain have closed, blaming high rents, the slump brought on by the coronavirus pandemic, and keen competition.

Toast Books, which specialised in art and philosophy books, is gone. Anyone Cultural, which sold mainly cultural books and titles from Taiwan, switched to being online. The Popular Bookstore chain closed all its 16 shops.

But the arrival of the national security law in June last year, banning acts of secession, subversion, terrorism and collusion with foreign forces, has left other booksellers worrying about the danger of crossing “red lines”.

Books attacked, screenings cancelled: the impact of censorship in Hong Kong

Political activist and author Raymond Yeung Tsz-chun, a former liberal studies teacher who founded publishing house Hillway Culture in 2016, said he understood the pressure Wan felt.

“Hong Kong used to enjoy a reputation for its free press, and people were free to openly criticise the Beijing and Hong Kong governments. But now it seems everything can be subjected to the national security law,” he said.

Despite the complaints, no action has been taken against him or his publishing house.

“The problem now is that we do not know where, or what, the red lines are. The government does not tell us and we can only guess and risk crossing the line unintentionally,” he said.

Veteran publisher Jimmy Pang Chi-ming, who runs the Sub-Culture publishing company and is vice-chairman of the Hong Kong SME Publications Association, said he did not display any political books at the fair to “avoid trouble”.

“We have no problem with the law. If there are clear guidelines or rules, we will know what to avoid,” he said. “How can you expect people to follow your rules if they do not know what your rules are?”

After the law was introduced, public libraries removed books by opposition figures including Joshua Wong Chi-fung and Tanya Chan. In July, a public library employee was suspended after books by jailed media tycoon Jimmy Lai Chee-ying were displayed as recommended titles.

Secretary for Security Chris Tang Ping-keung triggered concern when he singled out the cultural and media sectors as an emerging source of threats to Hong Kong’s stability, saying some activists might choose “soft resistance” to promote independence.

Hong Kong libraries pull democracy activists’ books for national security review

Daniel Lee Dat-ning, founder of Hong Kong Reader bookstore in Mong Kok, said the law had left him feeling more anxious about tightening restrictions.

“I removed books that explicitly mentioned Hong Kong independence or touched on the subject in some chapters. We are businessmen and do not want to risk being involved in anything illegal,” said Lee, a co-founder of the opposition-friendly Intercommon Institute, a platform promoting the discussion of current affairs.

Political analyst Chan Wai-keung, from Polytechnic University’s Hong Kong Community College, said there was no need for booksellers to be too worried.

“So long as you don’t go too far to provoke the authorities by publishing a book that advocates independence, it seems the authorities will still turn a blind eye,” he said.

He said he had seen anti-communist titles, especially in English, at larger bookstore chains, including some mainland China-backed ones.

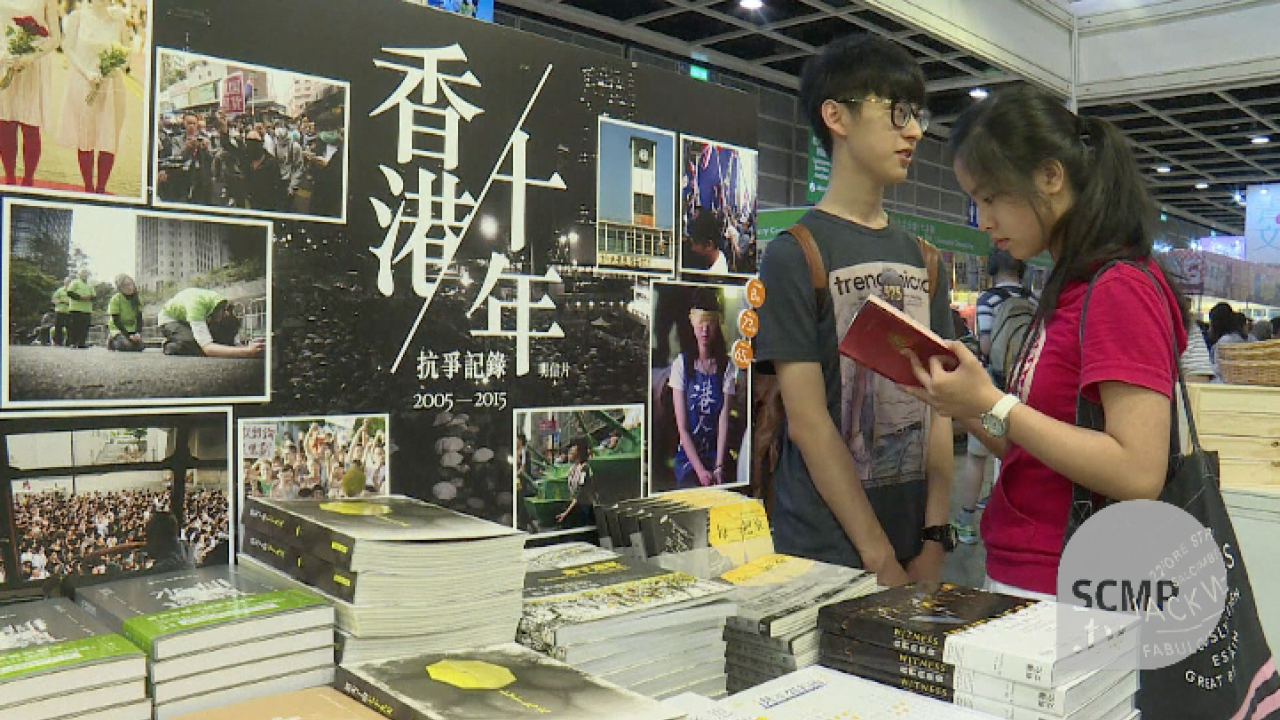

01:13

Publishers take on China at Hong Kong book fair

One bookseller who has seen his business grow in recent years is Daniel Mok Sze-wai, owner of second-hand bookstore My Book Room, which has a main store and two branches. He is opening his fourth shop in Sham Shui Po this month.

“There are ups and downs, but the market is not really so bad,” he said. He started his business six years ago, and his shops specialise in philosophy, history and literature, but also stock romance fiction and children’s books.

“Selling used books has an edge because sometimes we can get the books free of charge from people who move or have no space to store so many books at home,” he said.

Mok said he was not too bothered by the security law.

“I used to sell books about Hong Kong independence and they were quickly snapped up. They are probably collectors’ items now,” he said.

Books by opposition figures still sold at Hong Kong Book Fair despite complaints

Independent bookshop owner Phyllis Chan Lap-ching, who runs The Book Cure in Tai Po, said her business also grew by about 20 per cent through the pandemic.

“People who were bored at home wanted something to read,” Chan, who opened her shop five years ago, said.

Activist-turned-bookseller, So Keng-chit, a close friend of the late pro-democracy heavyweight Szeto Wah, said he was not concerned about the security law, as his Sun Ah Book Centre in Mong Kok sold mainly second-hand academic books on Chinese history, literature, art, and culture, and seldom stocked political titles.

“A bookstore should establish its own style. The more specialised it is, the more it can attract like-minded fans or readers. We did not lose a lot of readers because of Covid-19,” he said.