Hong Kong chief executive election 2022: why this year’s leadership race is unusual

- Observer says Beijing is biding its time on giving nod to favourites, as it does not want to fuel tensions in pro-establishment camp, while another notes lengthy campaigns not needed with narrowed political spectrum

- Current leader Carrie Lam has remained coy on a second bid, while no officials have resigned as in previous races to signal a possible run for top job

Hong Kong is witnessing an exceptional three-month countdown to the election of its next leader, with no clues yet on who will throw their hat into the ring.

It is unprecedented that no potential contender has launched a campaign, no incumbent official has resigned, and no signs have emerged of a Beijing favourite.

Lam touted her achievements, and also highlighted the importance of “continuity in government policies”.

Beijing exerts its hand in Hong Kong’s elections

State leaders offered no symbolic handshake – seen by observers as a signal of blessings from the central government – to Lam during her recent duty visit to Beijing, and the pro-establishment bloc in Hong Kong has remained silent on its preferred pick, although a few names have been floating in political circles.

Hong Kong’s fifth chief executive will be picked on March 27, under Beijing’s “patriots-only” overhaul of the electoral system, launched in the same month last year.

‘Big Brother is watching’: why Beijing ordered Hong Kong tycoons onto streets

The two-week nomination period for the chief executive race will kick off on February 15. Contenders need to obtain nominations from no fewer than 188 members of the 1,448-strong Election Committee that is stacked with pro-establishment figures, and at least 15 nominations from each of its five sectors. They are also required to pass a new national-security vetting system to qualify as candidates.

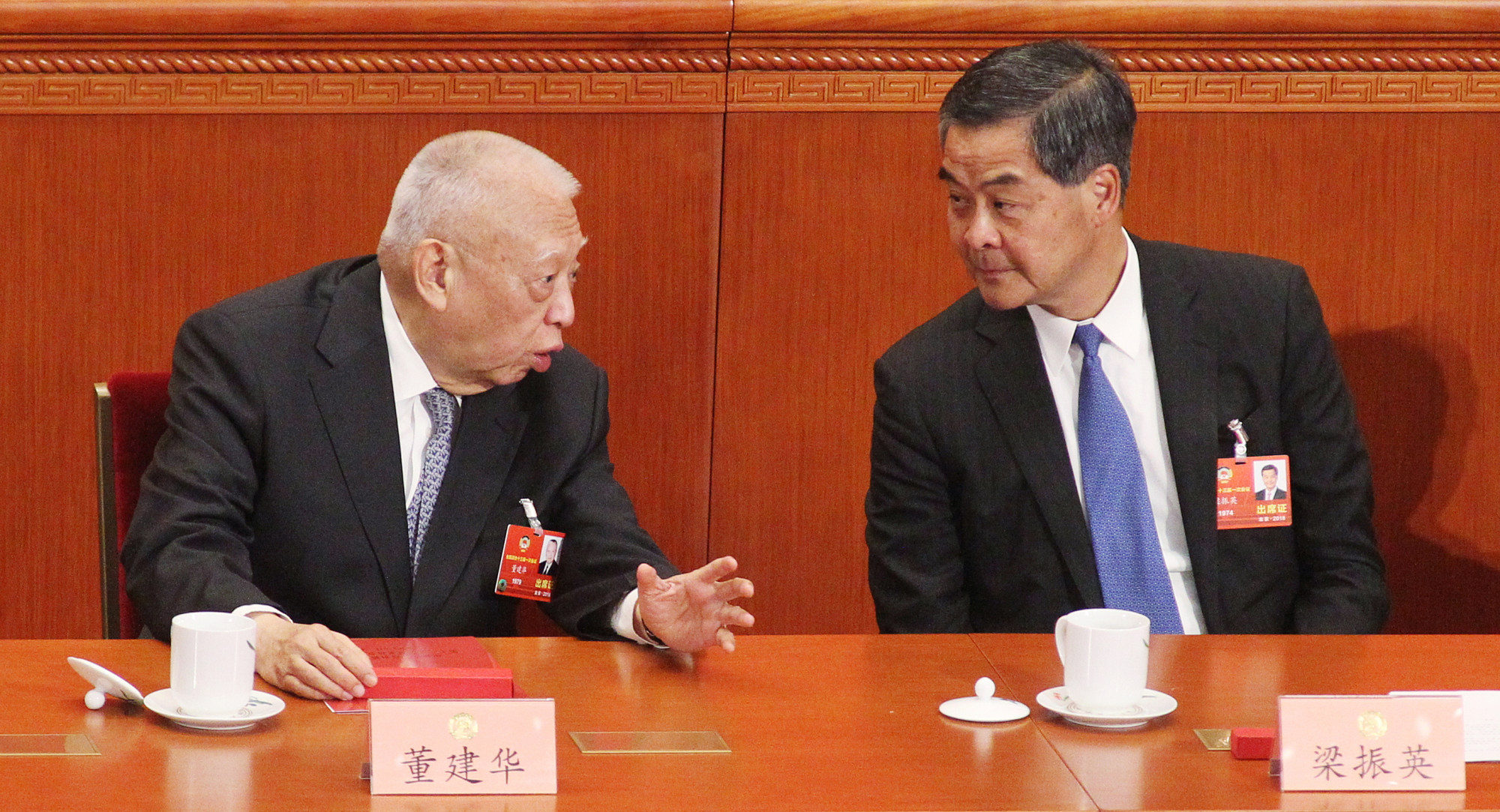

All four previous chief executive elections were held in late March except the inaugural race in December 1996 in which Tung Chee-hwa was returned as Hong Kong’s first postcolonial leader. Previous races witnessed early starts to election campaigns, with some kicking off up to half a year before election day.

In the 2017 leadership poll, retired judge Woo Kwok-hing jumped to an early start on October 27, 2016, five months ahead of the election, with a campaign against then leader Leung Chun-ying. Woo’s move paid off, as he captured sufficient nominations, mainly from the opposition camp, to enter the race.

On December 12, 2016, then financial secretary John Tsang Chun-wah resigned, paving the way for his eventual announcement of his bid for the top job. Tsang’s resignation came three days after Leung revealed he would not seek a second term, citing family reasons.

On January 12, 2017, then chief secretary Carrie Lam stepped down from her post. Lam and Tsang launched their campaigns after the State Council approved their resignations on January 16 that year. Lam won on March 26 with 777 votes from the 1,194-member Election Committee.

Incumbents in the 2012 race resigned even earlier. Half a year before the poll, Leung, then an Executive Council convenor, as well as chief secretary Henry Tang Ying-yen, quit the government in late September 2011.

That was the first race featuring more than one pro-establishment candidate. Former Democratic Party chairman Albert Ho Chun-yan threw his hat into the ring as early as October 2011. On November 26 and 27 that year, his two pro-establishment rivals announced their bids.

In 2006, Civic Party leader Alan Leong Kah-kit formally stated his intention to enter the contest on November 6, as the first opposition hopeful to run for the top job. He was defeated by then chief executive Donald Tsang Yam-kuen, who did not announce his re-election bid until less than two months before election day.

Speaking on condition of anonymity, a veteran pro-Beijing politician attributed the unprecedented slow start to this year’s race to the drastic change in the election cycle.

“Beijing hopes the new lawmakers in the revamped Legco will receive some public attention when a new term starts in January. This is a demonstration of unity … Early campaigns on the chief executive race will distract public attention,” he said.

Professor Song Sio-chong, from Shenzhen University’s Centre for the Basic Laws of Hong Kong and Macau, conceded that with fewer than 90 days to go before the chief executive race, hopefuls were “on a very tight schedule” in terms of campaigning.

But Beijing might want more time to observe and ensure the candidate line-up would not escalate the divisions and infighting within the pro-Beijing bloc as in previous races, Song said, adding there was no harm in a late start.

“It’d be better for Beijing to refrain from indicating its preference too early. This is to avoid a perception that the mainland is taking control,” he said.

The membership of the Election Committee, formed every five years to decide who leads the city, has been expanded from 800 in 1998, to 1,200 in 2012 and 1,500 under Beijing’s latest overhaul. The panel has been criticised for its “small-circle” electorate base favouring pro-Beijing interests.

In 2017, pro-democracy professionals and activists managed to clinch more than 300 seats on the body. Now, the revamped committee is tightly controlled by the pro-establishment camp, with the presence of only one moderate, social worker Tik Chi-yuen.

Following Beijing’s political shake-up, panned by critics as designed to silence dissent, Andy Ho On-tat, former information coordinator during Donald Tsang’s administration from 2006 to 2012, said he believed lengthy campaigns were no longer necessary.

Ho said in previous polls, there was room for contenders from the opposition bloc, such as Leong in 2007 and Albert Ho in 2012, to disseminate their political views to the general public through the election, while their pro-establishment rivals devoted time to crafting their own messages to voters.

But this will not happen in the impending race, according to Ho who now runs a public affairs consultancy. He pointed to the narrowed political spectrum which he said would prevent any non-pro-establishment hopeful from entering the arena.

“Whoever is running, they will hold very similar political visions … There won’t be much to fight over. The competition will be just like Omicron versus Delta,” he said, referring to variants of the coronavirus.