Can Hong Kong integrate with China’s Greater Bay Area? Start-ups, researchers upbeat on potential despite Covid-19 hurdles

- Entrepreneurs and professionals say Beijing’s measures to cut red tape, encourage start-ups and get young people to move have helped

- Technology and professional services sectors have gained most from changes over past three years

It has been three years to the day since Beijing announced the ambitious Greater Bay Area Outline Development Plan. In the first of a two-part series, Tony Cheung examines how Hong Kong has integrated with the region so far, and what lies ahead.

Hong Kong entrepreneur Ronald Tse Chi-hang, 39, remembers the difficulties he faced after co-founding healthtech start-up MVisioner in Shenzhen in 2015.

But the registration of new medical technology systems was centralised in Beijing, the process was slow, and it could take a year or two for a new product to be cleared for use in mainland Chinese hospitals.

“The taxation and many other policies were unfavourable to Hong Kong people, so we could hardly hire any Hongkongers even though we interviewed many candidates,” he recalled.

China’s Shenzhen plans will transform Greater Bay Area, including Hong Kong

Tse remembered that mainland authorities followed up by working with the Hong Kong and Macau governments to introduce various measures, including allowing people from the two cities who were living in Guangdong to apply for residence permits which gave them access to more public services. As of February last year, more than 300,000 Hong Kong residents on the mainland had applied for the permits.

“Since then, the mainland government has rolled out a lot of measures to retain talent, especially those with doctoral degrees and those who are from Hong Kong and Macau,” he said.

His company also benefited when a new medical systems registration and assessment centre was set up in Shenzhen, shortening the registration process by at least half a year.

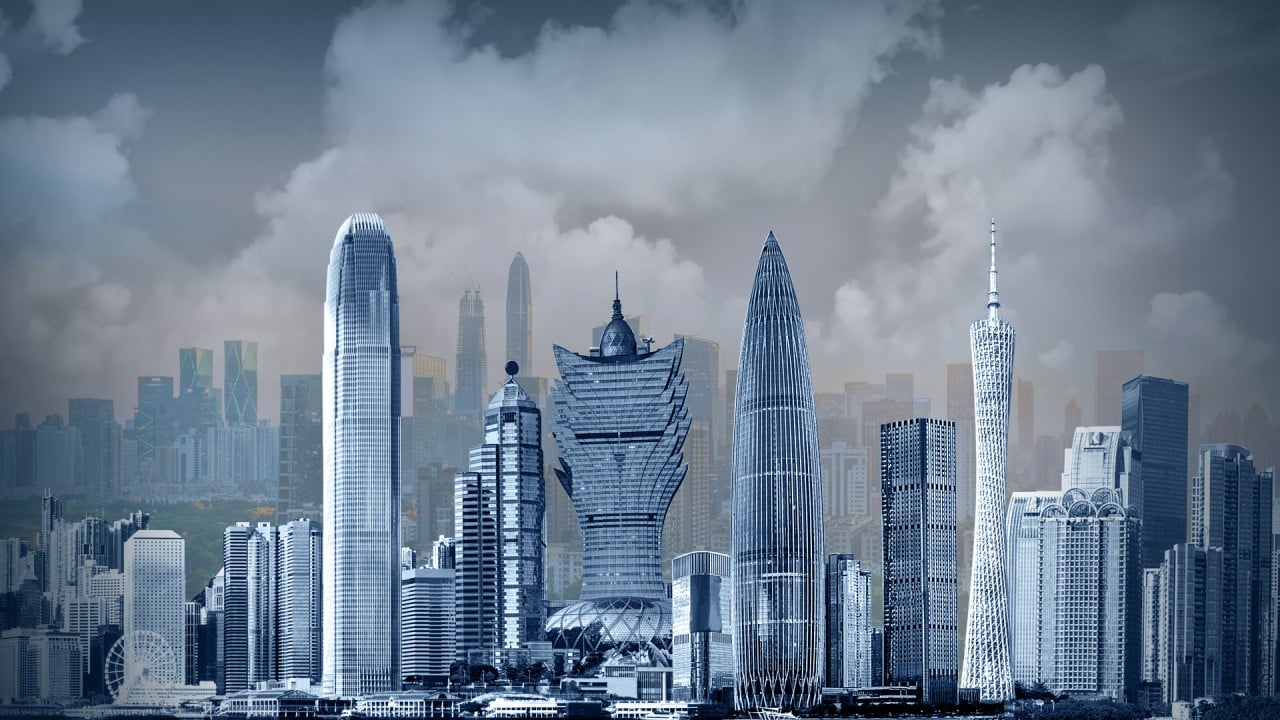

The 11-chapter blueprint specified that Hong Kong, Macau, Shenzhen and Guangzhou would be the core cities in the bay area plan, with the others being Zhuhai, Foshan, Huizhou, Dongguan, Zhongshan, Jiangmen and Zhaoqing.

They would be expected to work together to transform the region into a global innovation and technology hub.

The blueprint said that by 2022, the bay area would “have boosted its economic strength significantly through deepened cross-border cooperation”, and by 2035, the region would be “fully established as a world-class city cluster” where people would want to live, do business and visit.

‘Real changes in just three years’

Wingco Lo Kam-wing, executive vice-president of the Chinese Manufacturers’ Association of Hong Kong, said Hong Kong businessmen had been investing in the nine cities in the Pearl River Delta since the nation’s opening up in the 1980s, but the bay area project elevated the region to a national strategic level.

“In the past, different cities had their own direction, but with the 2019 outline, the region’s overall development became more coordinated,” he said. “The blueprint told us how each city should develop and integrate with each other. Hong Kong also has a clearer role as a global technology hub.”

Tommy Yuen Man-chung, the Hong Kong government’s bay area commissioner, said that the ambitious project was “based on the notion of complementarity and mutual benefits”.

“Hong Kong has long established itself as an international financial, transportation and trade centre with world-class professional services and strong research capabilities, while Shenzhen is the country’s innovation and technology hub, and Guangzhou, Dongguan and Foshan are globally influential industrial belts and manufacturing bases. We can leverage these complementary advantages to develop an international first class [bay area],” he said.

Between 2017 and 2020, the GDP of the bay area grew by about 6 per cent, from US$1.58 trillion to US$1.67 trillion, while its population jumped 28 per cent, from 67.6 million to 86.2 million.

According to latest figures, the GDP of the nine Guangdong cities grew by a further 7.9 per cent, to about 10 trillion yuan (US$1.59 trillion) last year.

Hong Kong’s economic growth last year was estimated to be 6.4 per cent, with actual figures to be unveiled by Financial Secretary Paul Chan Mo-po when he delivers the budget on February 23. Analysts estimate that taking Hong Kong and Macau’s 2021 GDP into account, the GDP of the entire bay area could reach US$1.89 trillion – about the same size as South Korea’s economy.

The number of Hongkongers living in Guangdong has also risen 8 per cent, from 520,000 at the end of 2016 to 560,000 by the end of 2020.

Lo said these figures were acceptable, as Hong Kong experienced months of social unrest in 2019, and the bay area was hit hard by the pandemic.

Since 2019, mainland authorities have rolled out measures to push forward cross-border integration and innovation, with technology and professional services sectors gaining the most.

Kelvin Lei Chun-ran, 39, co-founder and chief executive of financial technology firm Aqumon, said the changes had helped the company recruit talent from all over the mainland for its Shenzhen office.

“The mainland introduced subsidy schemes for hi-tech talent. Hong Kong also launched a scheme for university graduates to work on the mainland,” he said.

Those interviewed agreed that for the bay area project to take off once the pandemic eased, more had to be done to encourage young Hongkongers to study or work on the mainland.

In an interview with the Post last month, former Hong Kong leader Leung Chun-ying said he hoped young Hongkongers would keep an open mind about working on the mainland because there could be higher-paying jobs and cheaper homes across the border.

Aware that many young people were questioning the future of Hong Kong and their own too, he said: “Where is their future? If not on the mainland, where?”

Leung was among leading pro-establishment figures urging authorities to provide more opportunities for Hong Kong’s young people and professionals in the bay area.

In January last year, the government introduced the GBA Youth Employment Scheme, through which Hong Kong companies receive HK$10,000 (US$1,280) per month for every local university graduate offered a job in the bay area’s nine mainland cities.

As of last month, 1,090 young people benefited. More than 700 were aged between 20 and 24, and nearly 500 took up professional roles.

Of the total, 377 worked in commercial services and 286 in finance; 689 went to Shenzhen and 250 to Guangzhou.

In a significant move for the Hong Kong’s professionals, hundreds of lawyers sat the first legal exam last July to qualify to practise mainland law in the bay area.

Veteran lawyer Chan Chak-ming, 54, president of the Law Society of Hong Kong, was among 590 solicitors and 67 barristers who sat the exam. Chan, who was among the 450 who passed, said it was a milestone for the city’s legal profession and especially for younger lawyers.

While lawyers are free to practise in any of the nine mainland cities in the bay area, neighbouring Shenzhen appeared an attractive choice.

On a visit last September to Qianhai, a Shenzhen economic zone destined for massive expansion, Vice-Premier Han Zheng called for closer cooperation between Hong Kong and Guangdong in developing legal services.

Yuen, the Hong Kong official, also said that China’s latest five-year plan, together with the bay area project and the Qianhai initiatives, would “create enormous opportunities for the economy, society and people’s livelihoods”.

“The Hong Kong government will take forward the various initiatives to leverage the central government’s support … give full play to our unique strengths to serve the country’s needs, and make good use of the [bay area] as the best entry point for better integration into the country’s overall development so as to build a brighter future for Hong Kong,” he said.

‘Give researchers more incentives’

Peter Yan King-shun, chief executive officer of Hong Kong Cyberport Management Company, said the bay area plan had benefited the technology sector in the past three years, and Beijing’s initiatives to develop Shenzhen promised a further boost.

Last month, Beijing announced new measures that included developing an international sourcing platform for semiconductors and other electronic components in Shenzhen, in a bid to advance China’s hi-tech self-sufficiency drive amid a race with the United States to overcome a global chip shortage.

Yan said: “We have been working with entrepreneurship platforms on the mainland … and signed cooperation agreements with Qianhai and various universities [in Hong Kong] to do more in their mainland campuses,” he said.

Chinese University and Baptist University have campuses in the bay area and five others have plans to expand there too.

Yan said the bay area project had already encouraged Hong Kong university graduates to start their own businesses in the city and across the border.

Yan said the number of companies under Cyberport grew to 1,000 over 15 years from 2003 to 2018, but rose sharply over the next three years to hit 1,700 last year.

Chair Professor Anthony Yeh Gar-on, of the department of urban planning and design at the University of Hong Kong, said the bay area project heralded a new era in which Hong Kong and Guangdong worked together to boost the region’s economy.

He said the Hong Kong government could learn from mainland and foreign examples to boost the development of tech products.

“Some say our professors are not hungry enough, but that’s because the incentive for development is not sufficient,” he said. “University professors have to apply for patents, but the patents are owned by the university.”

Yeh pointed out that researchers in some other countries were allowed to own their patents, while governments used their products to drive economic growth.

“We need to improve on this,” he said.

CY Leung says he ‘envies’ young Hongkongers for Greater Bay Area opportunities

Hong Kong technology sector lawmaker Duncan Chiu said the past three years were meant only for authorities to experiment with the Greater Bay Area project and pave the way for meeting the long-term goals of 2035.

“Hong Kong is one of the four core cities and won’t be marginalised. We cannot do everything by ourselves, so we need to work with our neighbours,” he said.

“But we are also a city which took a deep dive into financial technology and biotechnology, and we have a deep pool of talented personnel. Unless we are just lying flat and being complacent, we won’t be easily eroded and replaced by others.”

Aqumon’s Kelvin Lei, who settled in Hong Kong after growing up on the mainland, said he was confident that Hong Kong would not lose its status as a global financial hub any time soon.

“My Shenzhen IT colleagues are very diligent, but Hong Kong is the most internationalised city in Asia, its talent and professionals are very knowledgeable about East and West,” he said.