Hong Kong imitates Macau: one-man race showcases pro-Beijing camp’s unity but could risk alienating public, analysts say

- Macau’s solo candidates engage public, but residents with no say in outcome lose interest in polls, says one veteran former opposition lawmaker

- Pro-Beijing observer says this year’s race not a sign Hong Kong will have no vigorous contests in future

Hong Kong appears to be going the way of neighbouring Macau in choosing its next leader, with a single candidate running a compact campaign and supported by pro-Beijing political heavyweights.

The gaming hub has seen one-man races in four out of its five leadership elections since it was handed over from Portuguese to Chinese rule in 1999.

In Hong Kong, John Lee Ka-chiu, a police officer who rose to become the city’s No 2 official, has emerged as the sole Beijing-backed hopeful for the leadership election scheduled for May 8.

Lee kicked off his campaign on Saturday, with the help of pro-Beijing think tanks, political pundits and public affairs specialists. He said his three primary focuses were to achieve results, boost Hong Kong’s competitiveness and reinforce the city’s foundations.

While some viewed the one-man race as Beijing’s opportunity to showcase unity in the pro-establishment camp, others said the no-contest election was no more than a “political show” which did little to strengthen the prospective leader’s legitimacy to hold office.

‘John Lee set to pocket enough nominations to run in Hong Kong’s leadership race’

“Beijing is trying to turn Hong Kong into another Macau … [but] an uncontested election clearly undermines public participation in the political process,” said political analyst Eilo Yu Wing-yat, an associate professor at the University of Macau. “Political elites like to compete and bargain behind closed doors. But the public does not have much say in such negotiations.”

Hong Kong’s chief executive election will be the first one-man show since 2005 when the city’s second leader, Donald Tsang Yam-kuen, won unopposed. Macau, on the other hand, had a contested leadership race only once, its first in 1999. All four subsequent elections featured only one candidate.

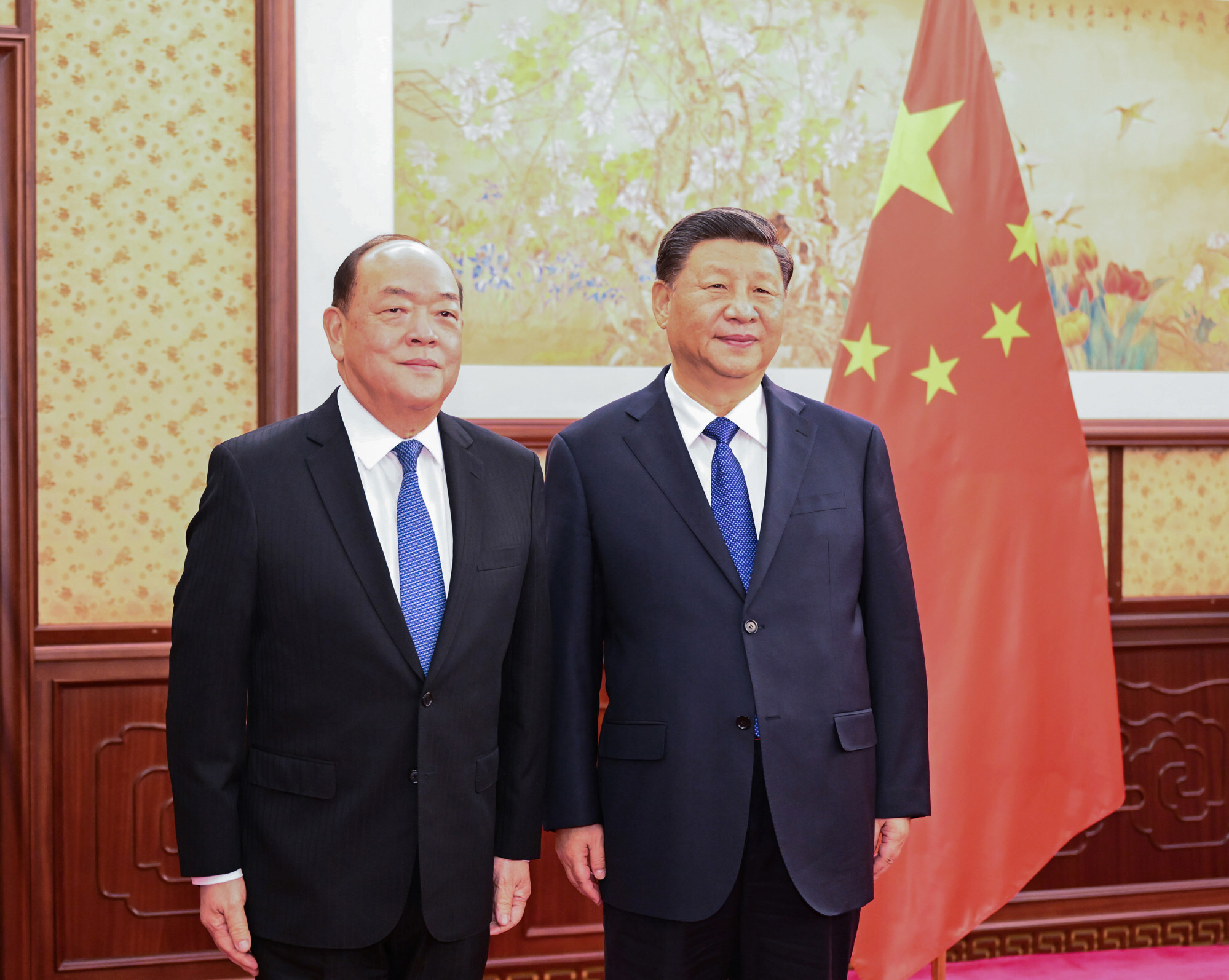

In August 2019, at the height of anti-government protests in Hong Kong, Macau’s current leader Ho Iat-seng won 98 per cent of the vote from its 400-strong Election Committee.

Ho stepped up two months before the election, announcing his bid at the landmark Macau Tower. He set up a 6,000 sq ft campaign office and recruited the city’s elites to help him gather 379 nominations to run.

Then he invited all Election Committee members to the Macau East Asian Games Dome, where he unveiled his political platform and declared that he stood for a “clean and efficient government with a diversified economy”.

Ho went to great lengths to address questions from committee members eligible to vote and the media, explaining that he intended to reach out to all strata of Macau society through more than 40 public events during the two-week campaign period.

Even though there were committee members who asked questions, there were limitations with the campaign, according to political analyst Yu.

“Public views might not necessarily be reflected. There was no debate on policies,” he said.

When Ho’s predecessor, Fernando Chui Sai-on, former secretary for social affairs and culture, announced his intention to run in May 2009, there was speculation that Ho Chio-meng, a former civil servant in Guangdong province, might also join the race.

But after Chui secured 286 nominations from the then 300-member Election Committee, it was clear that no other contender would obtain enough backing to run. In the end, he won with 94 per cent of the vote.

Looking back, Bruce Kwong Kam-kwan, assistant professor of public administration at the University of Macau, said Chui banked on the network of the city’s first chief executive, Edmund Ho Hau-wah, to woo support from committee members.

“Chui appeared to lack an elite power base,” he said.

Ho himself faced a contest for his first term but ran unopposed for his second term in 2004.

He made a point of reaching out extensively to commercial chambers, industry circles and ordinary residents, focusing on the need to diversify Macau’s economy and his concerns over the shortage of professionals.

Ho was endorsed by 297 members of the 300-strong committee and was re-elected with 99 per cent of the vote.

Au Kam-san, a veteran former opposition lawmaker in Macau, recalled that throughout Ho’s campaign, there was no mention of democracy or proposals relating to political reforms.

Unlike Hong Kong’s Basic Law, the city’s mini-constitution, which enshrines the goal of universal suffrage in choosing lawmakers and the chief executive, Macau’s legislation makes no mention of widening the pool of voters.

Au said surveys conducted in Macau over the years had shown a desire for universal suffrage in the leadership race.

“Elections that were one-man shows effectively silenced the discussion of issues not favoured by Beijing, resulting in stagnation of the city’s development on democracy,” he said. “People gradually became uninterested in election campaigns.”

Why did John Lee emphasise ‘result-oriented’ method for governing Hong Kong?

Instead of adopting the “Macau model” for its leadership race, Hong Kong should encourage competition even with Beijing’s electoral reforms, as the financial hub had a vibrant political culture, he said.

But Lau Siu-kai, vice-president of the semi-official think tank, the Chinese Association of Hong Kong and Macau Studies, said he saw Hong Kong’s one-man race as a “necessary, exceptional” arrangement amid external and internal challenges that could haunt the city’s development over the next five years.

In the ever-changing rivalry between global superpowers, he said, Beijing did not wish to see infighting within the pro-establishment camp that could become obstacles to Hong Kong’s governance.

“But we don’t need to assume that the one-man race is the ‘new normal’ under the electoral overhaul,” he said. “Beijing has all the flexibility to allow competition, perhaps after the city’s pro-Beijing forces achieve better solidarity.”