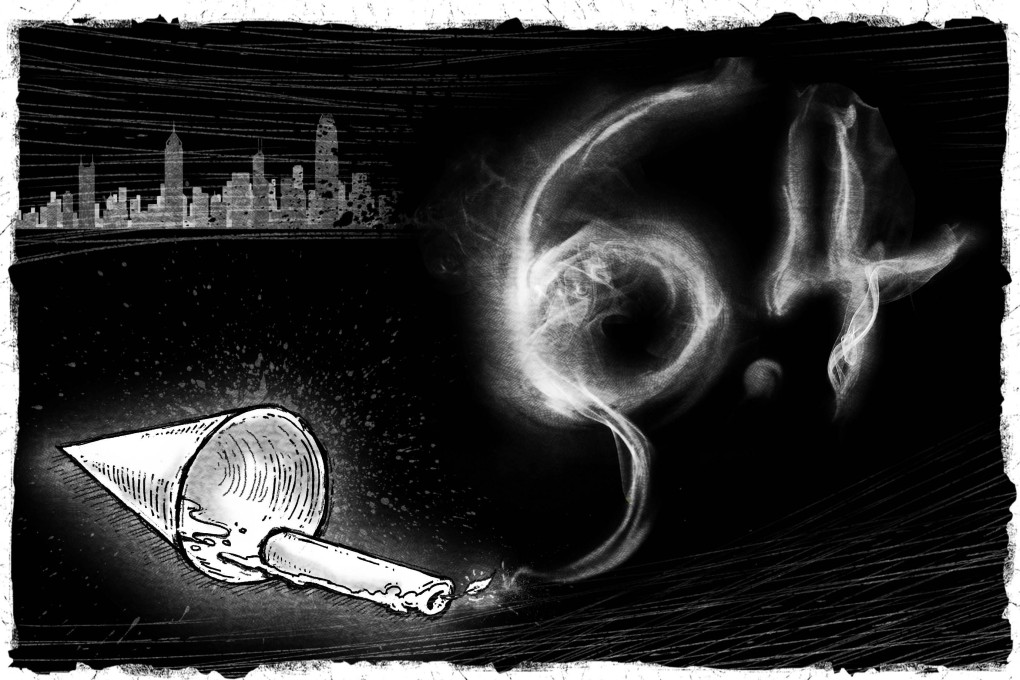

Remembering the Tiananmen Square crackdown: with no June 4 vigil in Hong Kong, will memories fade or can overseas events carry the torch?

- Group behind annual vigil disbanded last September, while HKU removed sculpture marking crackdown in December 2021

- Overseas commemorations of event have taken on greater significance this year, especially as more Hongkongers have moved out of city

It is a route Wei Siu-lik remembers by heart. She knew where to turn, where to cross, where to pause but mostly she cherished the sense of camaraderie with others who ran alongside her.

But this year, Wei and three friends were left on their own to carry on their decade-long tradition on May 22, after event organiser, the Hong Kong Alliance in Support of Patriotic Democratic Movements of China, which was behind the annual candlelight vigil marking the crackdown anniversary, disbanded last September.

Three core leaders of the alliance were charged with subversion under the national security law imposed by Beijing in 2020 and which also bans acts of secession, terrorism and collusion with foreign forces.

Apart from having to accept that some of her running peers were now behind bars amid a new political landscape, Wei also found it hard to believe the Pillar of Shame was gone.

Last December, HKU removed the eight-metre sculpture in light of “external legal advice and risk assessment”. Depicting a mass of writhing, tortured bodies, the artwork, a gift to Hong Kong from Danish sculptor Jens Galschiøt, was regarded as a June 4 icon.

A day after HKU’s move, Chinese University and Lingnan University followed suit, removing a statue known as the Goddess of Democracy and tearing down a wall relief respectively, both symbols marking the crackdown.

“Things have taken a drastic turn at a fast pace,” Wei, a former district councillor, said. “I still remember we decided to start in Tsim Sha Tsui because we wanted to promote the cause to mainland tourists there. But now maybe even Hongkongers will refrain from sharing any posts related to the crackdown on social media.”