Explainer | How will Hong Kong’s district council overhaul change neighbourhood political life? Direct voting curbed, lines redrawn in ‘patriots-only’ revamp

- Last piece of governance reform puzzle falls into place, following Beijing’s implementation of national security law nearly three years ago

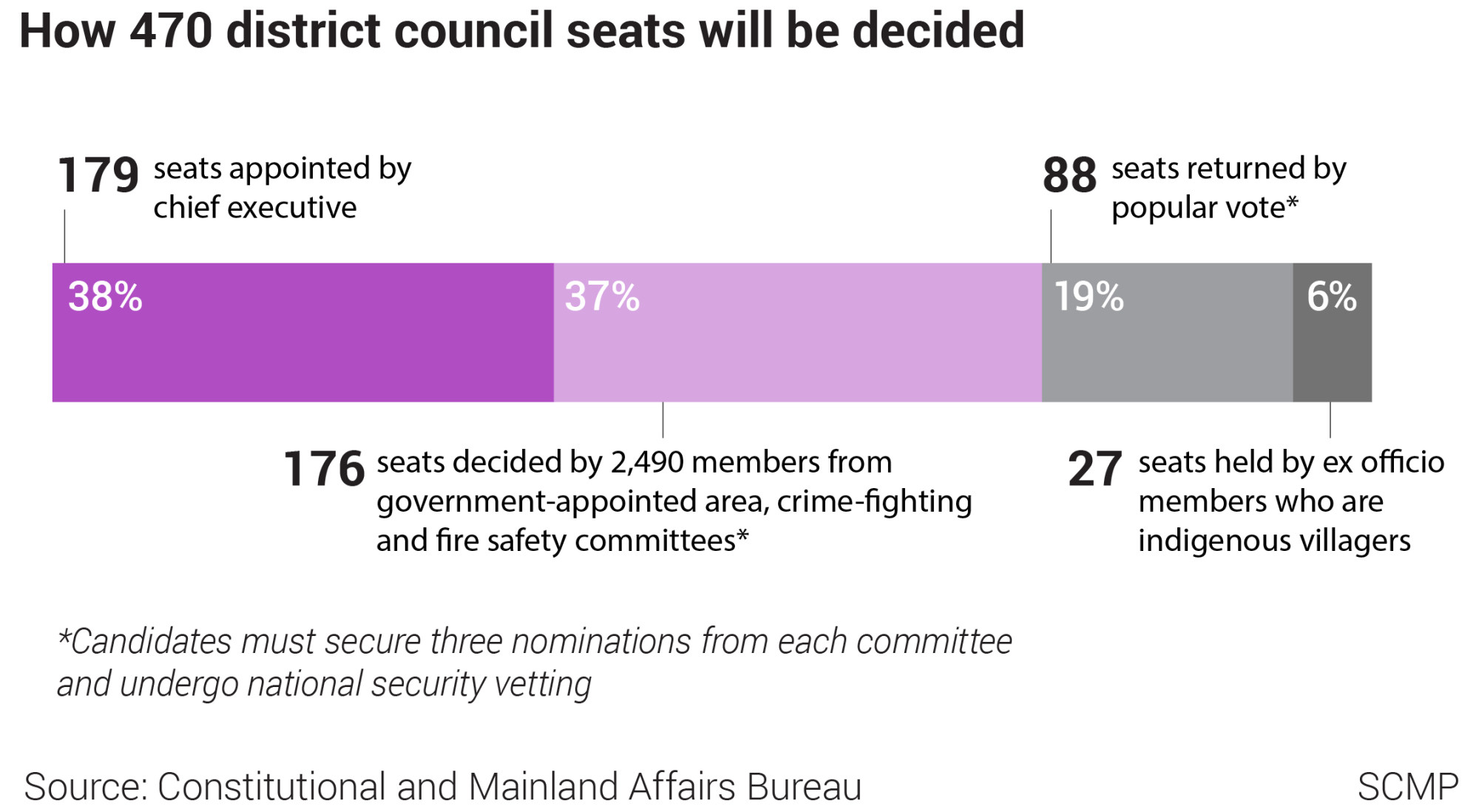

- Out of 470 seats across 18 new district councils, only 88 will be chosen by city’s four million registered voters

Here, the Post walks through the history of the municipal-level bodies and explores what the future holds.

What are Hong Kong’s district councils?

The councils were created in 1982 as district boards with the purpose of obtaining better advice and participation from residents. Each of the 18 bodies represents one of the administrative districts across the city.

The Home Affairs Department specified that the councils were to advise authorities on matters affecting the well-being of residents, as well as government-run programmes, public facilities and services in the district.

The bodies were handed the power to approve funding for small projects under the community involvement and district minor works programmes in 2007. Those powers were taken back by the government in October 2021.

What is their current state?

The proportion of directly elected seats has fluctuated before and after the city’s return to Chinese rule in 1997, but it had largely been on a gradual upwards trajectory before the latest overhaul.

Appointed seats were first eliminated in 1994 under British rule, restored after the handover and fully scrapped again in 2016.

With the first district boards, 132 out of the 489 seats were directly elected. In the current-term district councils, 452 seats were popularly chosen under a “single seat, single vote” system, in which each constituency was represented by a single councillor. There were another 27 rural leaders who served as members on the councils.

What changes are in store?

Out of the 470 seats across the 18 new district councils that have their terms starting next year, only 88 will be chosen by the more than 4 million registered voters in Hong Kong.

District lines will be redrawn to reduce the number of constituencies to 44. Each voter will have one vote to elect two representatives in each constituency.

Appointed seats, abandoned since 2016, will be brought back. Authorities will choose 179 councillors to take up seats.

Another 176 seats will be picked by government-appointed members of three existing neighbourhood committees set up in the districts, namely the District Fight Crime Committees, the District Fire Safety Committees and the Area Committees.

Going forward, Wan Chai district, for example, will be one single constituency served by two directly elected representatives, down from the current 13. There will also be eight other councillors appointed by the government or chosen by the three neighbourhood bodies.

Would-be councillors must secure three nominations from each of the three committees to qualify for the race, in addition to the 50 made by constituents. The requirement will also apply to those eyeing one of the 176 seats to be chosen by the three bodies.

As part of the reform, the district councils will be grouped under a structure supervised by the Steering Committee on District Governance, which will be chaired by the city’s No 2 official.

The proposal is subject to approval by the Legislative Council, which has been under full control of government-friendly lawmakers since 2021. Little resistance is expected.

Why are district councils being revamped?

Chief Executive John Lee Ka-chiu said the move was designed according to three guiding principles: to put national security first; to advance the goal of “patriots administering Hong Kong”; and to further the administrative-led principle.

Lee defended the overhaul as necessary to put the municipal-level bodies back on the right track of serving residents and prevent the platforms being used to promote separatism.

He said the new proposal, which merged “fragmentised” constituencies into bigger areas, would help future councillors see the big picture better while taking care of local matters.

All levels in Hong Kong’s electoral system will have undergone a makeover once the latest proposal is passed, as similar overhauls were put in place for the last Legco and chief executive elections after China’s top legislature decided in March 2021 to overhaul the city’s politics in the wake of the 2019 social unrest.

What are the reactions so far?

Pro-Beijing parties voiced unanimous approval for the reform.

The New People’s Party, headed by Executive Council convenor Regina Ip Lau Suk-yee, argued the district councils had become highly politicised. She referred in particular to the aftermath of the 2019 election, as many councillors were elected based on their political stance and support for anti-government protests rather than district experience.

But political scientists such as John Burns, of the University of Hong Kong and Ma Ngok, of Chinese University, lambasted the plan as a “regression” that might prevent the government from being informed about public opinion.

The Democratic Party, the city’s largest opposition group and which did not field any candidates for the Legco poll last year, will later decide whether to take part in the coming district council election after weighing the pros and cons with members.