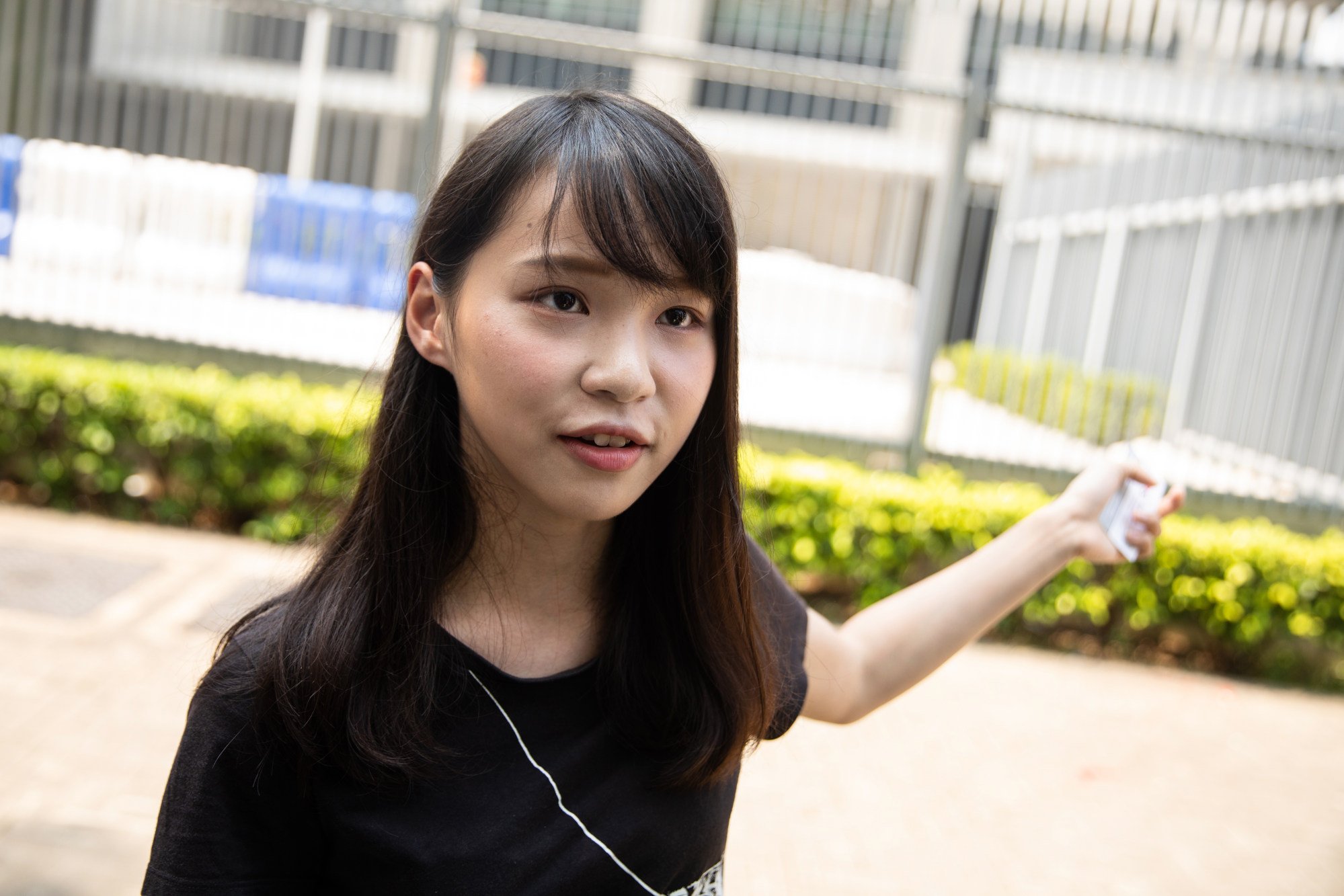

Hong Kong police can ask for ‘repentance letters’ and patriotic trips as part of bail terms, key government adviser says as concerns over Agnes Chow’s claims mount

- Conditions Agnes Chow claims were imposed on her are permitted so long as both parties agree to them, Senior Counsel Ronny Tong says

- But another activist and lawmaker question whether such ‘mainland’ practice will become new norm and call on government to clarify its stance

Hong Kong police’s alleged demand that activist Agnes Chow Ting write “repentance letters” and pay a patriotic visit to mainland China before she could go overseas is in line with the law, a government adviser has said amid concerns the requests may become a new norm in the city.

Chow on Sunday said she had to write “letters of repentance” expressing regret over her past political activities and vowing to sever ties with her former allies, as well as make a day trip to Shenzhen accompanied by police officers, as among the conditions to get her passport back so she could leave for Canada in September to study for a master’s degree.

According to Chow, she was requested to pose for photos with exhibits and signboards when visiting an exhibition in Shenzhen about the country’s economic reforms and the headquarters of internet giant Tencent.

Apart from the “repentance letters”, she also claimed she was required to write a letter of gratitude to police for arranging the trip so she could “learn about the accomplishments of the motherland”.

Senior Counsel Ronny Tong Ka-wah, who sits on the key decision-making Executive Council, brushed off concerns on Monday that the unprecedented conditions would infringe upon Chow’s civil rights, arguing the activist had agreed to them to study overseas.

“Once you’ve offended the law, you don’t have a right to leave [the city], as the law stipulates, unless police permit them to leave,” he said.

Bail conditions were usually decided by police and the arrested person, with no defined limits to the conditions as long as both parties agreed to them, Tong noted.

But an opposition activist who declined to be identified said the arrangement was “unbelievable”.

He felt it was grossly unfair of the police to have confiscated Chow’s passport and limit her movements for more than three years without deciding to charge her.

“The requirement to write repentance letters or make a trip across the border is very mainlandised, and it is hard to imagine that there are such arrangements in Hong Kong,” the activist said, questioning the effectiveness of such moves in changing people’s political views.

He feared such practices would become accepted as a new norm in Hong Kong. “Will forced televised confessions be brought to Hong Kong next?” he said.

Hong Kong police have yet to respond to a Post request for comment.

Centrist lawmaker Tik Chi-yuen said that while the practice of writing letters of repentance was common on the mainland, it was rare in Hong Kong. Tik said he had never heard of activists being sent on national education trips to the mainland and expressed doubt over the effectiveness of such short trips in changing the perspective of opposition activists.

Tik also urged the government to clarify whether Chow’s allegations were true, saying: “This practice is new to Hong Kong and the relevant authorities have to explain the reasoning and considerations behind it, or else people will interpret things differently and cause speculation.”

Professor Simon Young Ngai-man, associate law dean at the University of Hong Kong, preferred not to comment on Chow’s case given the limited information available. He noted police bail was granted to a person suspected of committing an offence but who had not been charged.

“The police perceive the person is at risk of offending or absconding and wish to keep the person within their radar,” he said. “Thus, it is not unusual if conditions of police bail are agreed such that the conditions can help to manage these risks while giving the person a wider latitude of freedom.”

Chow is the first public figure in the city to make claims about being forced to write such letters, which is a practice common on the mainland, and to make a trip across the border as part of bail conditions.

The force’s National Security Department on Monday called Chow’s refusal to return to Hong Kong “irresponsible”.

It said Chow had been cooperative and reported to the force on time. Without confirming or denying the Shenzhen trip, it only said it issued her with a travel document and extended her bail until September this month after she provided documents proving she had been accepted by an overseas institution.

Tencent also did not respond to requests for comment.

Additional reporting by Jeffie Lam