Exclusive | Social activist kicked out of Hong Kong finally returns to city after 46 years, and says ‘need to speak truth to power’ is as great as ever

- Daniel Roche helped form Society for Community Organisation, and worked helping resettle poor left homeless by reclamation and storms

- But giving voice to these groups drew ire of colonial government

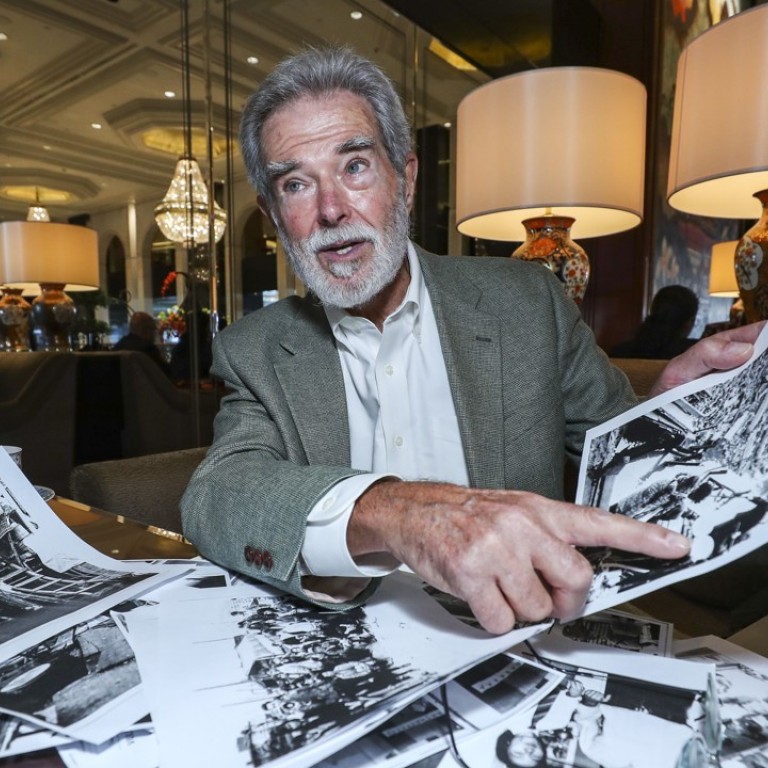

Forty-six years ago social activist Daniel Roche was kicked out of Hong Kong by the colonial government – this month he finally returned to the city for the first time since 1972.

Four decades on, and while there are more lines on his face, and more grey in his beard, the passion for social justice that burned then does so just as fiercely.

“It’s crucial to speak truth to power, speak for the powerless, and empower the poor to fight for their own rights,” the 79-year-old told the Post.

When Roche left in 1972, he vowed to return after “defeating colonialism” abroad. Much has changed in the intervening years, and while Hong Kong is no longer a British colony, and unrecognisable from the city he left, Roche still sees the same challenges that prompted SoCO’s creation all those years ago.

“It is unconscionable that Hong Kong does not do more to provide subsidised housing for the poor, given the billions of dollars in surplus,” he said.

The American first came to Hong Kong in 1971, after he was hired as a consultant by religious leaders and social workers who wanted to set up an organisation to fight for the rights of ordinary people.

He arrived in July and immediately began mentoring five trainee community organisers.

Homeless in Hong Kong: a cycle of despair for evicted street sleepers

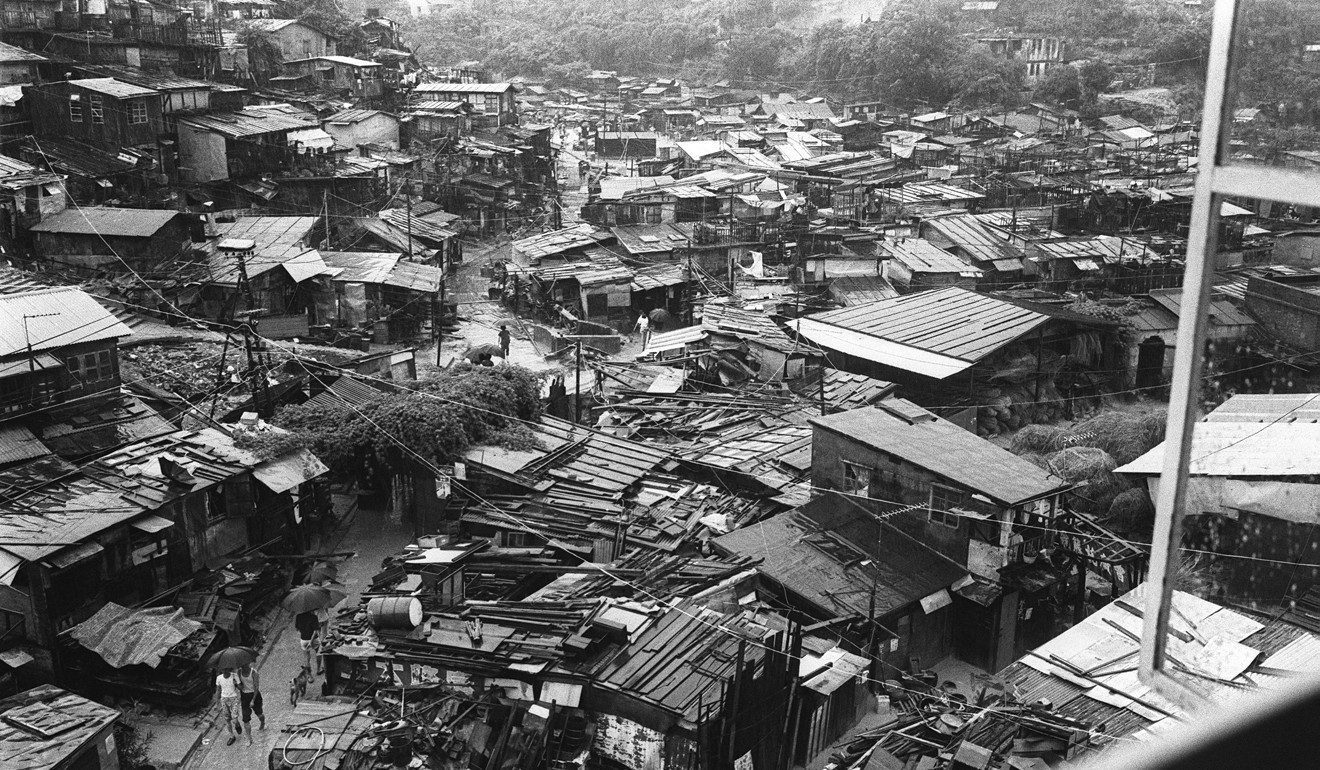

Their first project was to help about 3,500 people in the Yau Ma Tei Typhoon Shelter get rehoused, after they were displaced from their boat huts because of reclamation work at Tai Kok Tsui.

The following year the group helped residents living in squatter huts in Tai Hang Tung get resettled after storms had left them homeless.

Dan never talked about theories. We acted, reflected, and acted through trial and error.

Joe Leung Cho-bun, one of the community organisers trained by Roche, said the American activist avoided lecturing, and instead shared his experiences with them.

“After sending us around to different communities to explore issues for organising, we had regular discussion and sharing. He would mainly asked questions,” Leung said.

Leung, an honorary professor with the University of Hong Kong’s department of social work and social administration, said they learned from student movements at that time.

“We simply used sit-ins, mass meetings, petitions, marches to draw press attention, exercising indirect pressures on government,” he said. “Obviously the government had never experienced such a challenge before.

“Dan never talked about theories. We acted, reflected, and acted through trial and error. He was supportive and encouraging.”

Pao Ping-wing, one of the community organisers trained by Roche, said the American sent them to districts to identify problems that needed to be resolved.

“He then asked us to raise the awareness of residents, and identify resident leaders to organise among themselves to fight for their own rights,” Pao said

Roche said the success of the grass roots organisation quickly drew the ire of the colonial government, and in August 1972 his flat in Lai Chi Kok was raided by police.

“They didn’t have a search warrant and they said ‘we didn’t need a search warrant’,” Roche said. “They found a paper clip containing 0.1 gram of marijuana.”

Roche said he got the paper clip from a friend in Chicago as souvenir, and then brought it to Hong Kong.

“The colonial government considered me a troublemaker. That was a convenient way to get rid of me,” Roche said.

He was found guilty of “possessing a pipe intended for smoking dangerous drug” and he was told he must leave the colony by October 15 that year.

The American said Francis Hsu Chen-ping, then bishop of the Catholic diocese of Hong Kong, who supported the community organisation’s work, protested to the governor against the deportation.

Hong Kong heatwave left city’s poorest reduced to tears and fighting off depression

“I was moved when about 70 friends, mostly boatpeople from the Yau Ma Tei Typhoon Shelter, and former Tai Hang Tung squatters, came to see me off at Kai Tak Airport,” he said.

The activist went to India to take part in community organisation there for about one year, and then returned to the United States to continue his work. He retired in 2007.

“When I knew I was about to be deported, I felt that community organisation must go on in Hong Kong, and it [his departure] was not the end of the world,” Roche said. “I’m inspired by the continuation of the work of the SoCO, despite my deportation.”

During his visit, he met Ho Hei-wah, the present director of SoCO, and returned a crucial chapter of history – a folder of documents about the early days of the organisation, which Roche had kept for 46 years.

In contrast to his departure, Roche had no trouble getting a visa to return to the city, and travelled to Beijing on Saturday as part of his trip. From there he will move on to Xian and Chongqing.

A protégé of Saul Alinsky, a leading radical organiser of deprived groups in the United States and author of a book titled Rules for Radicals, Roche’s passion for helping the underprivileged remains undimmed by his advancing years.

He visited residents living in subdivided flats in Sham Shui Po on Friday.

“I felt overwhelmed with compassion for the poor people living in wretched conditions,” he said. “I was so impressed with the dedication and professionalism of the SoCO staff.

“Hong Kong needs the organisation as much today as it did when I was here more than 40 years ago.

“But I don’t think the Hong Kong government has done enough to address social ills. The wealth gap is widening in the city. It’s unjust and unfair.”