Life through a lens: veteran photojournalist’s 28-year career told in 40,000 rolls of film

● Former South China Morning Post chief photographer talks dark rooms, developing and dodging rioters to get the perfect picture

Chan Kiu is no flash in the pan. Thirty-one years after his retirement from the South China Morning Post, the respected lensman, who celebrated his 91st birthday last month, is still widely regarded as the quintessential Hong Kong photojournalist, as well an icon of the newspaper.

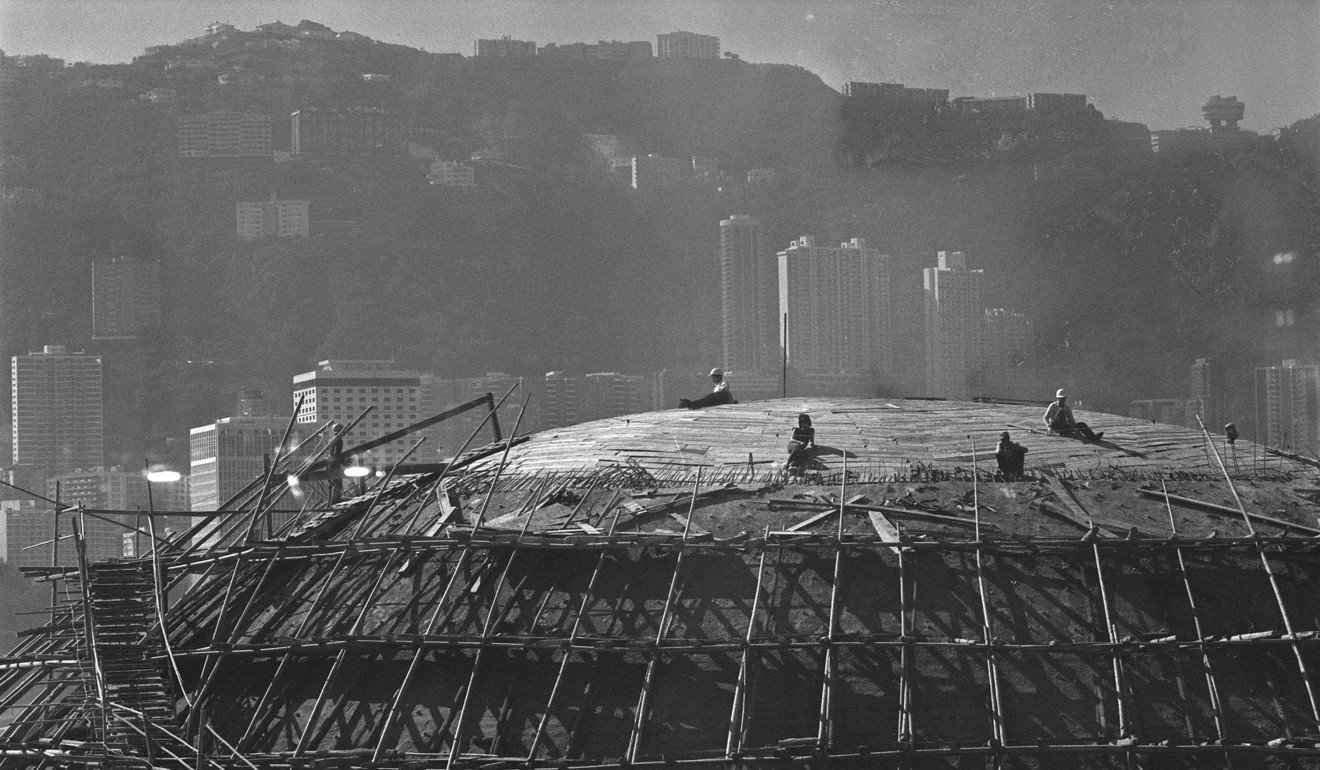

Having shot close to 40,000 rolls of film in his 28 years at the Post, Chan captured, in his vivid images, some of the most decisive moments – riots, bombings, typhoons, floods, landslides, celebrations, royal and papal visits, and air and sea disasters – that would later come to define history.

In the best traditions of the Post, Chan has never been one to compromise when it comes to getting the best pictures. It is no overstatement to say Chan set the benchmark in news photography that had an impact.

But, with his usual matter-of-fact attitude, Chan declined to admit that it was anything extraordinary. “I was just an ordinary news photographer. It just so happened that I was sent by the editor to cover the news events,” says the silver-haired, svelte veteran photographer, who has lived with his family in Vancouver since 1993.

“You wouldn’t have time to think about recording history at the time when you pressed the shutter button. They were just history caught in a hurry.”

Chan is known to one and all in the Hong Kong media circles as “Uncle Kiu”. The endearment refers to the way he selflessly imparted his knowledge to younger photographers, and to his longevity in the industry. In 1985, he became the first local press photographer to be awarded the Badge of Honour by Queen Elizabeth for his service and contribution to the Hong Kong media industry.

Chan was born in Hong Kong in 1927 to a working class family. His father died when Chan was five years old, and he and his younger sister were raised by their mother, who operated a fish stall at the market. Chan would get up before dawn every day to help man the stall for her.

During the Japanese occupation of Hong Kong in the early 1940s, the family fled across the border to their hometown, Dongguan in Guangdong province. They returned to Hong Kong after the war and opened a food shop.

It was not until the early 1950s that Chan decided his life should be “a little more spicy”. He turned to photography. It was also around this time he got married, in 1952.

To help support his family, the young Chan learned some basic photography skills by reading books, and then set his camera up to take instant photographs for visitors at the recently opened Tiger Balm Garden, next to Haw Par Mansion in Tai Hang.

Having received only informal education to primary level, Chan attended evening English classes to better himself. In 1956, he joined the then Hong Kong Tiger Standard as a darkroom assistant, being later promoted to sports photographer.

He has never forgotten the first time he set foot in a darkroom to develop film. “I set up a darkroom in my flat at that time to practise. You would be overwhelmed by a sense of wonder when you watched the image emerge on a piece of photo paper beneath the dim red light,” Chan says. “The only downside was the photo paper and the chemicals were expensive.”

At that time, he says, his monthly pay at the Tiger Standard was HK$250. Three years later, he moved to the Post, where he would spend the rest of his career. By the time he joined, the paper had already established its reputation as one of East Asia’s leading newspapers.

In those days, only English-language newspapers would hire specialised news photographers; in the Chinese-language ones, reporters would be expected to take pictures themselves, mainly for budget reasons.

“The Post offered me HK$350 a month. It was a big newspaper. Did you think I thought twice about it?” Chan says.

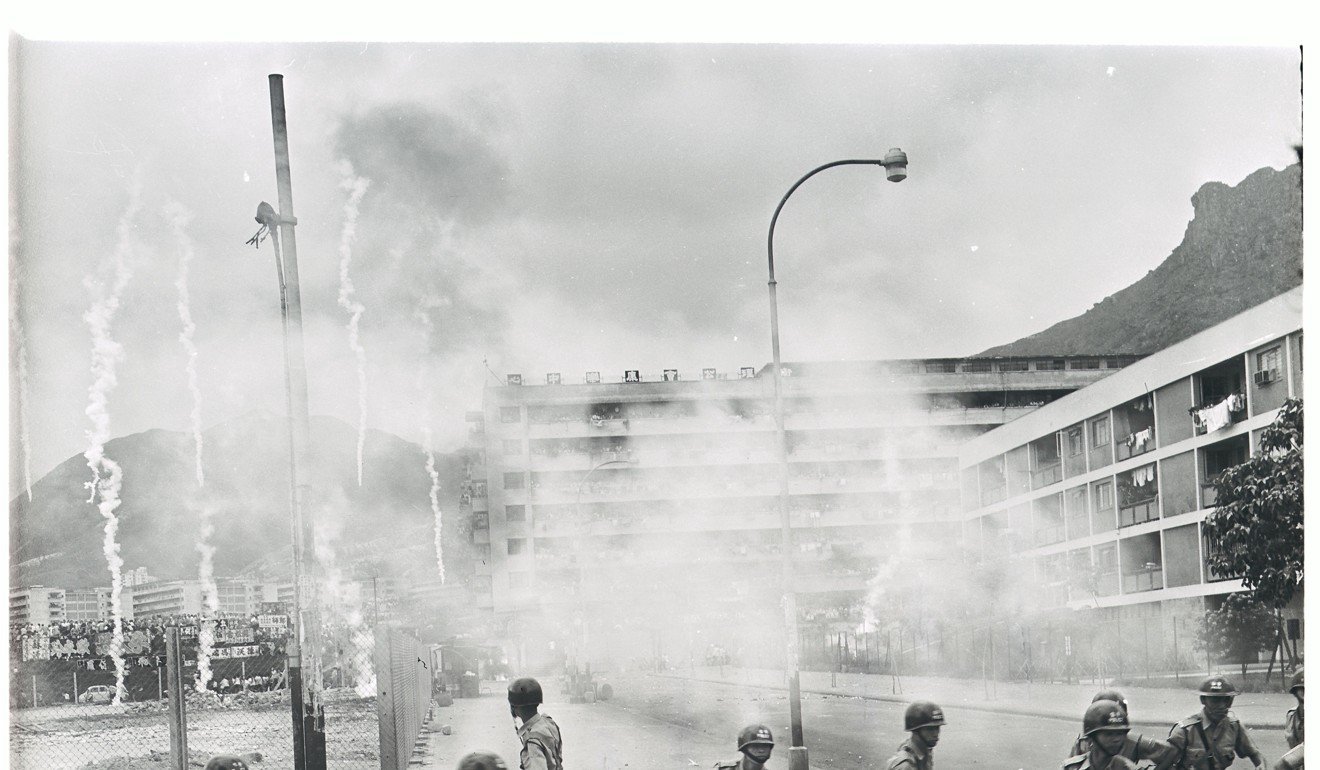

His favourite work was hard news. And the 1967 leftist riots in Hong Kong were a good example of the work he enjoyed most – dangerous but exciting.

And there is one memory that has stayed with Chan ever since.

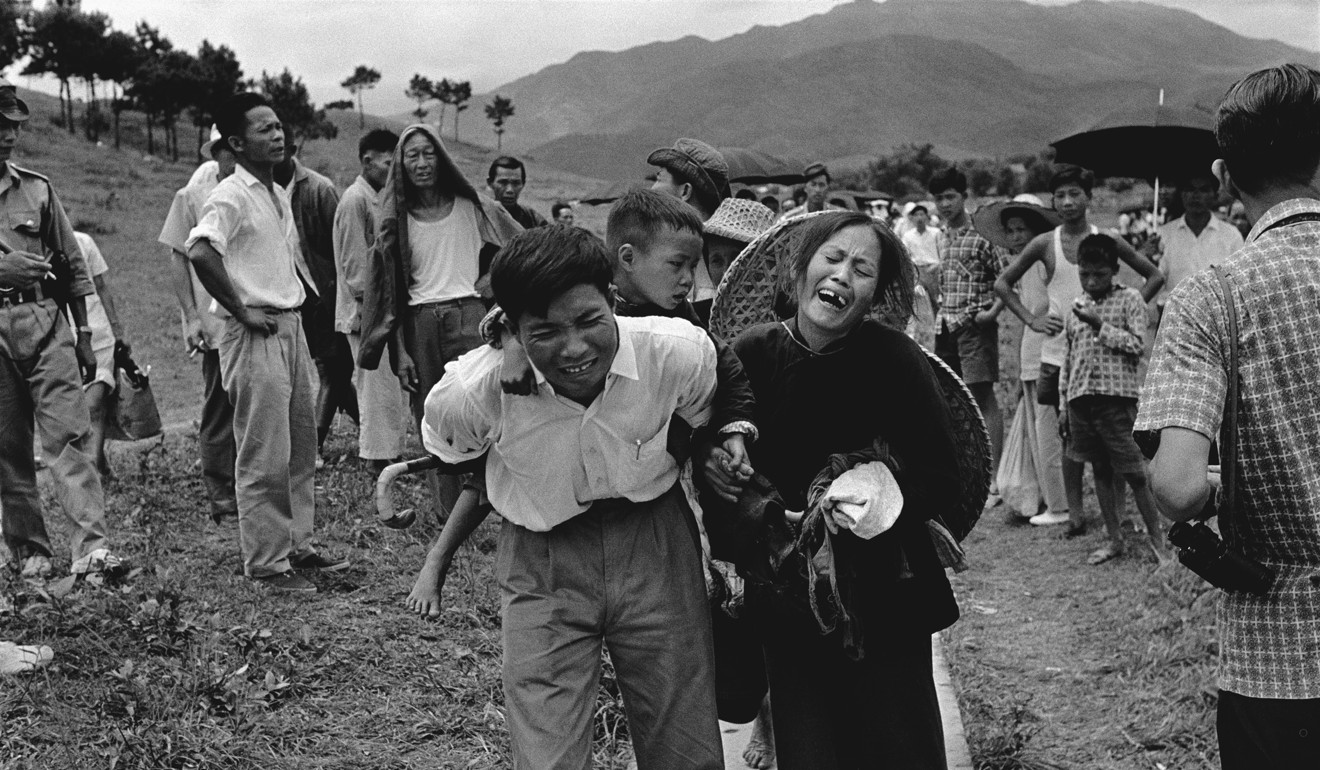

It was in May 1967, when street protests and violence were gaining momentum and more blood was being spilled, Chan was sent to cover a protest by factory workers in San Po Kong.

“What had started as a regular protest by workers against their employers quickly developed into a potential riot, with hundreds of rioters coming face-to-face with a heavy police presence. It was not a situation I was unused to. Only the previous year, I had covered the Star Ferry riots,” says Chan, referring to the 1966 riots triggered by the British colonial government’s decision to allow second-class fares on the Star Ferry to be raised by five cents, or 25 per cent.

“Photographers knew they were playing with fire. It was important to keep your distance or you could end up with a knife in your back. But that time in San Po Kong, two of us suddenly found ourselves surrounded by a group of rioters. The other photographer managed to escape, but I couldn’t and they started to punch me and tried to smash my camera.”

Fearing for his life, Chan got help from an unlikely source. “A leftist protest leader stepped in and told the mob I was just doing my job. They took my film before letting me go. I had to take three days off to recover from the injuries,” he says.

But that was not the only time during the riots that year that Chan came face-to-face with violence.

About two weeks later, a car he was in with another photographer and two reporters was stopped by a crowd at the junction of Waterloo Road and Shanghai Street, in Yau Ma Tei.

“The police had been searching for left-wing leaders in Sham Shui Po and we were on our way back to the office after covering the story,” Chan says. “When we were stopped at the junction, the rioters saw one of the reporters in our car and thought he was European. He was in fact Eurasian, There were about 40 or 50 of them. He was the driver and they opened the door and tried to pull him out.

“While this was happening, someone threw a stone through the windscreen, injuring one of the reporters. Luckily, our driver was a big strong man. He managed to free himself from the rioters and drove off at top speed.”

For almost a year, Chan found himself in the thick of the action during the communist riots, often dodging bricks and bottles aimed at police, and at risk from the many bombs left scattered about the territory by the leftists.

“Without doubt that was the most dangerous period of my career,” Chan says.

The attacks on Chan and his fellow reporters during the riots prompted local reporters to set up a trade union to represent and safeguard their rights. The Hong Kong Journalists Association was established in 1968, with Jack Spackman, a one-time news editor of the Sunday Morning Post, as its founding chairman.

In an interview last year with OMNI Television, in Canada, Chan said the Occupy Central protest in Hong Kong in 2014 “was nothing at all” when compared to the 1967 riots he had witnessed.

“Hong Kong is a small place and has many people. But it has always been peaceful. … The 1967 riots were influenced by the Cultural Revolution in China,” Chan said in the interview. “Hong Kong is so close to China. Hong Kong gets independence? That is impossible, right?”

His images of the 1967 riots also made him one of Hong Kong’s great photojournalists. But that did not come easy.

“In photojournalism, good news sense and being prepared, not expensive equipment or hard technical skills, matter the most,” Chan says.

For Chan, being prepared meant lugging about 7kg of equipment, including three manual cameras, six lenses, and at least six rolls of film, which Chan complained had made one shoulder lower than the other.

During his illustrious career, he won more than 30 awards in Hong Kong and abroad. One of his best remembered winning pictures was taken during the floods of 1966, of a woman falling into the water in Sai Ying Pun. The only thing the picture did not tell was that Chan stood knee-deep in floodwater for almost an hour waiting for it to happen.

“I knew somebody would fall. A photographer cannot lose his patience. He must keep waiting for a good picture and a good chance,” Chan says.

But there were times when Chan had to wait for decades for another chance to take a picture. In 1961, Chan captured the sentimental moment of departing British solider Tony Caller bidding farewell to his Chinese girlfriend, Dorothy So, on the wharf at Tsim Sha Tsui.

The picture was published in the Post with a caption that read: “Tony Caller of 32 Medium Regiment RA says his last goodbyes to pretty Miss So Yun-mai, just before the UK-bound troopship Nevasa sets sail.”

The love story went on, and Caller and So got married and started a family in Britain the following year. In 1975, the pair returned to Hong Kong, and met Chan again in 1979 at a photo exhibition in Chan’s honour. The couple and Chan kept in touch and in 1987, Chan took another photo of the couple at the same spot to celebrate their 25th wedding anniversary.

They had hoped Chan could do the same again for their golden anniversary in 2012, but unfortunately that was not to be. Over the years, the photographer and the couple lost touch, until social media reunited Chan and So once more in 2017.

The reunion, however, was a bittersweet one. Caller had died from cancer 22 years before. So, however, remains alive and well, living in Britain. She and Chan chatted over the phone, according to Chan’s children.

The episode showed not only the beauty of romance, but also the value of old news photography.

“I am not a romantic person. But I like to meet old friends and see old friends meet. When I have time, I would like to return to Hong Kong to visit my old friends there,” Chan says.

Chan has no regrets about putting so many years of his life into his profession, although his family sometimes complained because he was too busy to spend time with them.

“Since my retirement, I have been taking things more easy and spending more time with the family,” he says.

Chan has seven children, seven grandchildren, and two great grandchildren. Most live in Canada.

“Life in Vancouver is much quieter and more peaceful than in Hong Kong. I usually do dim sum with my family on Sundays. Funny enough, I used English more often when I was with the SCMP than since I’ve moved here.

“In the Chinese community here, the main language is Cantonese. But I think I still manage to understand the stories in the SCMP,” Chan laughs.

His popularity has not receded though, and he is regularly involved in charity and volunteer work serving Vancouver’s Chinese community. He has also had some photography exhibitions given in his honour.

Among fellow journalists and friends, Chan’s excellence in tai chi almost rivals his photojournalism skills.

Chan says he has practised tai chi for 40 years. “I do it to keep fit, for at least half an hour a day. It improves my health. Unlike most forms of physical activity, tai chi demands focus, which is central to its meditative benefits. I feel my mind is sharpened after doing it;”

Word has it that he can manage the standing toe-touch exercise with ease.

The seasoned photographer also says he seldom uses an SLR camera to takes pictures these days. “I bring a compact digital camera to take some casual snapshots while travelling.”

But, Chan is quick to add that he would never stop taking photographs. “Few things are more exciting for me than the camera,” he says.

And, while he has embraced digital photography, he still says he has his limits. “I don’t use computers to edit images. I’m not great at using Photoshop, or computers anyway,” he says.

“I try to capture the best image with the digital camera instead of relying on image editors afterwards. Whether it’s digital or film, it is still important for a photographer to use his creative mind to take pictures that can make an impact, and not using computers to edit or recreate his pictures.

“This should also apply to news reporting, I presume, despite the shift in media landscape caused by the digital age. Content matters more than the medium by which they are conveyed,” Chan says.