Record 1.37 million people living below poverty line in Hong Kong as government blames rise on ageing population and city’s improving economy

- Official figures put number 25,000 higher than previous year, as poverty rate also hits seven-year high

- Chief Secretary Matthew Cheung denies claims government is not doing enough to combat problem in city

More than 1.37 million people in Hong Kong are living below the poverty line, struggling to survive in one of the most expensive cities in the world on as little as HK$4,000 (US$510) a month, according to official figures released on Monday.

A fifth of Hong Kong’s population is destitute, a seven-year high, while even with government intervention 17.5 per cent of the city’s children are classed as living in poverty.

But despite the number of poor reaching a record high for the second year running, Chief Secretary Matthew Cheung Kin-chung denied claims the government was not doing enough, and said an ageing population, an improving economy, and changing demographics had contributed to the high numbers.

The poverty line is set at 50 per cent of median monthly household income before taxation and the government’s policy intervention, which includes social welfare payments, such as allowances for the elderly and low-income families.

In real terms that means a single person with a monthly income of HK$4,000, a two-person household earning HK$9,800, while the threshold for a three-person household is HK$15,000.

According to the Hong Kong Poverty Situation report for 2017, 1.377 million of the city’s residents were living below the official poverty line, 25,000 more than the figure in 2016.

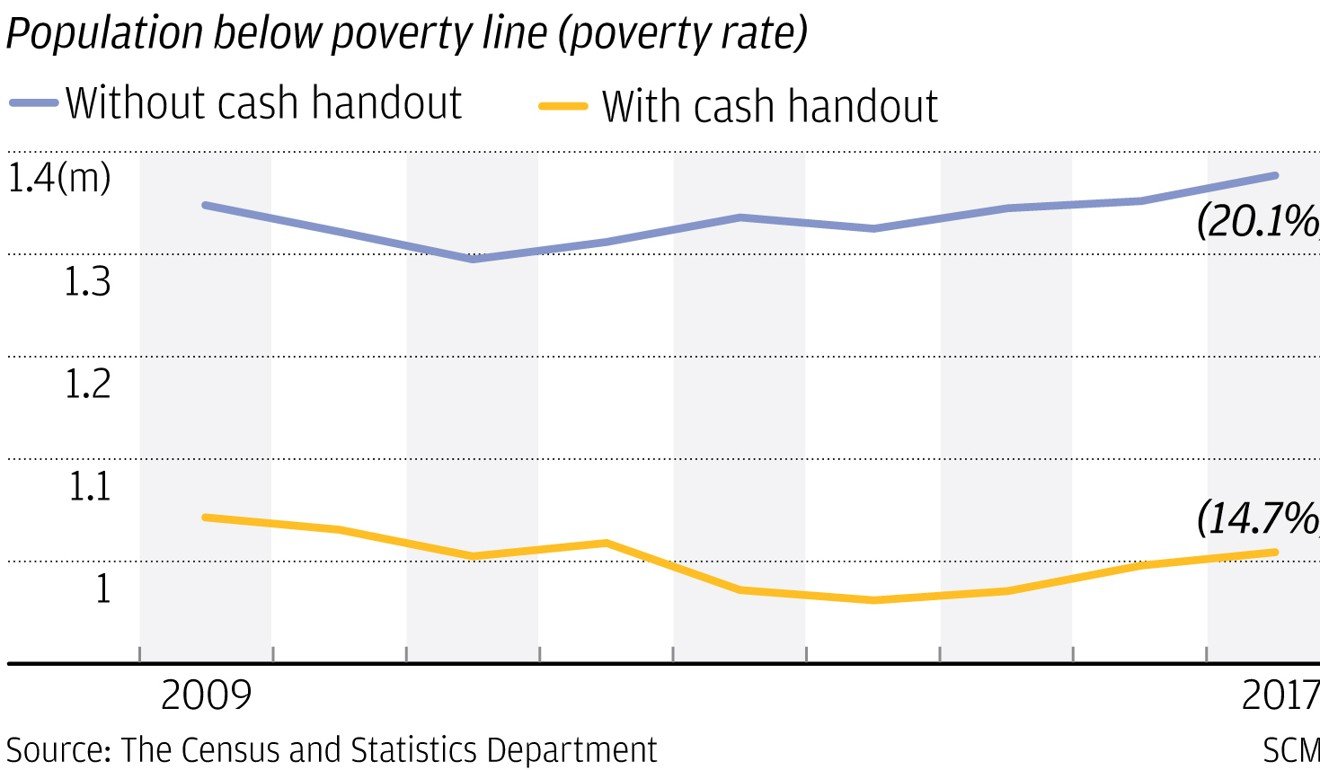

The poverty rate rose 0.2 percentage points to 20.1 per cent, which is the highest since 2010.

But, after taking the government’s cash handouts into account, the poverty rate fell to 14.7 per cent, or 1.01 million, a rate similar to the previous year.

“I don’t think our policies have failed at all,” said Cheung, who is also the chairman of the Commission on Poverty.

The chief secretary said the poverty rate after government intervention, was similar to the previous year, but the number had increased because of a bigger base of the entire population.

Cheung said there were limitations to the methodology for calculating the figures, with government support such as public rental housing and health care vouchers for elderly not reflected in the figure.

He said these were not included in order to follow international norms.

Cheung said Hong Kong’s economy expanded last year, and coupled with the increase in minimum wage from HK$32.50 to HK$34.50 per hour last year, income and wages of low-income employees had seen substantial improvement.

“As such, the poverty line threshold for different household sizes also went up,” he said.

But, Labour Party lawmaker Fernando Cheung Chiu-hung said the poverty figures were worrying when viewed in the context of a buoyant economy.

He said the situation could worsen if the economy took a downturn.

Fernando Cheung also called for more flexibility in the number of working hours and proof of working hours for the Working Family Allowance Scheme.

Non-single-parent households with aggregated monthly working hours not less than 144 hours may apply for Basic Allowance, while single-parent households with aggregated monthly working hours not less than 36 hours may apply for Basic Allowance under the scheme.

Sze Lai-shan, community organiser of the Society for Community Organisation said the Comprehensive Social Support Scheme, which supports families in need, such as those who are jobless, needed to be reviewed.

Whatever the true numbers, poverty is a blight on Hong Kong

“Children now need computers to do school work, we cannot just use a scheme with adjustment criteria set more than 20 years ago,” said Sze, who is also on the Commission on Poverty.

Going forward, the chief secretary said the government would engage ethnic minorities through religious groups to help them apply for the working family scheme, which many were not aware of.

He said he would also bring the findings on child poverty to the children’s commission, which he also heads, to analyse with the members.

Meanwhile, the government’s principal economist, Reddy Ng, said elderly residents living in domestic households increased significantly by nearly 50,000 in 2017, compared with just an average of 40,000 in the eight years before.

Unlike the past few years, most of these additional elderly lived in working households with non-elderly family members, resulting in lower income and a heavier financial burden for some households, she added.

Wake up to the crazy rich-poor divide in Hong Kong, and the government’s role in perpetuating the misery

But, Matthew Cheung said he believed the poverty situation would improve in the 2018 report with enhancements to the working family allowance scheme, formerly known as the low-income family scheme, made this year.

He said the recurrent expenditure on social welfare was expected to increase to HK$79.8 billion for the 2018-19 financial year. This is the second highest government expense, behind funding for education.

On a brighter note, the poverty rate after intervention for the elderly fell by 1.1 percentage points to 30.5 per cent, returning to the 2013 level.

But, for children that went up by 0.3 percentage points to 17.5 per cent.

Secretary for Labour and Welfare Law Chi-Kwong said the introduction of a free kindergarten scheme last year, which was not included as a government intervention policy as it is a non-means tested measure, meant a fee remission scheme for needy children was no longer counted as an intervention measure.