Why initially sceptical Hong Kong property tycoon Gordon Wu put his faith and money in Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping’s vision of reform

- Hong Kong entrepreneurs were among the first to head for mainland China after paramount leader announced country was on path of reform and opening up

- They started factories for everything from toys to textiles, built hotels and motorways, and played a crucial role in the tremendous changes to unfold over the next 40 years

When President Xi Jinping met a delegation of top officials and business leaders from Hong Kong and Macau in Beijing on November 12, he singled out property tycoon Gordon Wu Ying-sheung and praised him for building mainland China’s first superhighway.

But Wu, chairman of Hopewell Holdings, was initially a sceptic who wondered if China’s ambitions of economic reform and opening could ever take off, given the way things had been run for so long, with the state deciding everything.

His 1972 visit to Guangzhou for the Canton Fair, the mainland’s largest trade show, left a deep impression and it was not good.

He found everyone in Guangzhou dressed the same, in faded olive-green trousers and green cotton shirts, or grey trousers and grey shirts.

At a Chinese opera performance, he asked the 20-something woman seated next to him if she was married. “She said it wasn’t easy to get married because approval from the authorities was needed,” he recalled.

Travelling around Guangdong province, he saw slogans everywhere, saying: “Down with the class enemy!”

“I realised later that the signs referred to capitalists, and I was among the enemies to be toppled,” he said.

In 1977, he went on a 27-day sightseeing tour of the mainland with more than 20 Hong Kong business leaders, including Cheung Kong chairman Li Ka-shing.

Visiting a locomotive factory in the suburbs of Beijing, Wu was stunned when its head said the plant manufactured every single item it used, even screws.

Hong Kong: an awkward partner in China’s 40-year quest to open up

“I told him the size of screws was standardised around the world and it would have been more cost-effective to import them,” Wu said. “But he said the factory followed the instructions issued by the government under the planned economy.”

It was plain that productivity on the mainland was very low, as workers had no incentive to work harder.

So he was sceptical when China’s paramount leader Deng Xiaoping announced in 1978 that the country was going to reform and open up.

Wu said he read Deng’s speech several times before he realised fundamental changes were afoot and that Hong Kong’s future would be interwoven with that of the mainland.

“I was convinced that Hong Kong people wouldn’t have to emigrate if the mainland got rich gradually,” he said.

How Chinese entrepreneurship arose from the ashes of revolution

In 1979, he got together with tycoons Li Ka-shing, Lee Shau-kee, Cheng Yu-tung, Kwok Tak-seng and Fung King-hey and discussed building an international-standard hotel in Guangzhou, even at the risk of losing money.

“Li said, ‘This will be our first project in China, so it has to be of very good quality and it doesn’t matter if we make a profit,’” Wu recalled.

The group formed a US$125 million consortium, but their China Hotel project was slow to get off the ground because Guangzhou officials had no idea how to deal with the Hong Kong investors and their ways.

Wu wanted a prime site, but officials offered alternatives in the suburbs.

“They thought the location wouldn’t matter because the municipal tourism bureau would allocate visitors to different hotels,” he said. “But I insisted, and they eventually backed down.”

The 1,200-room hotel was built, and it was China’s biggest when it opened in 1984.

Getting the right staff proved another challenge because officials insisted that the local labour bureau would assign the workers needed. Wu had to turn to the Guangdong governor before he was given a free hand to hire the people he wanted.

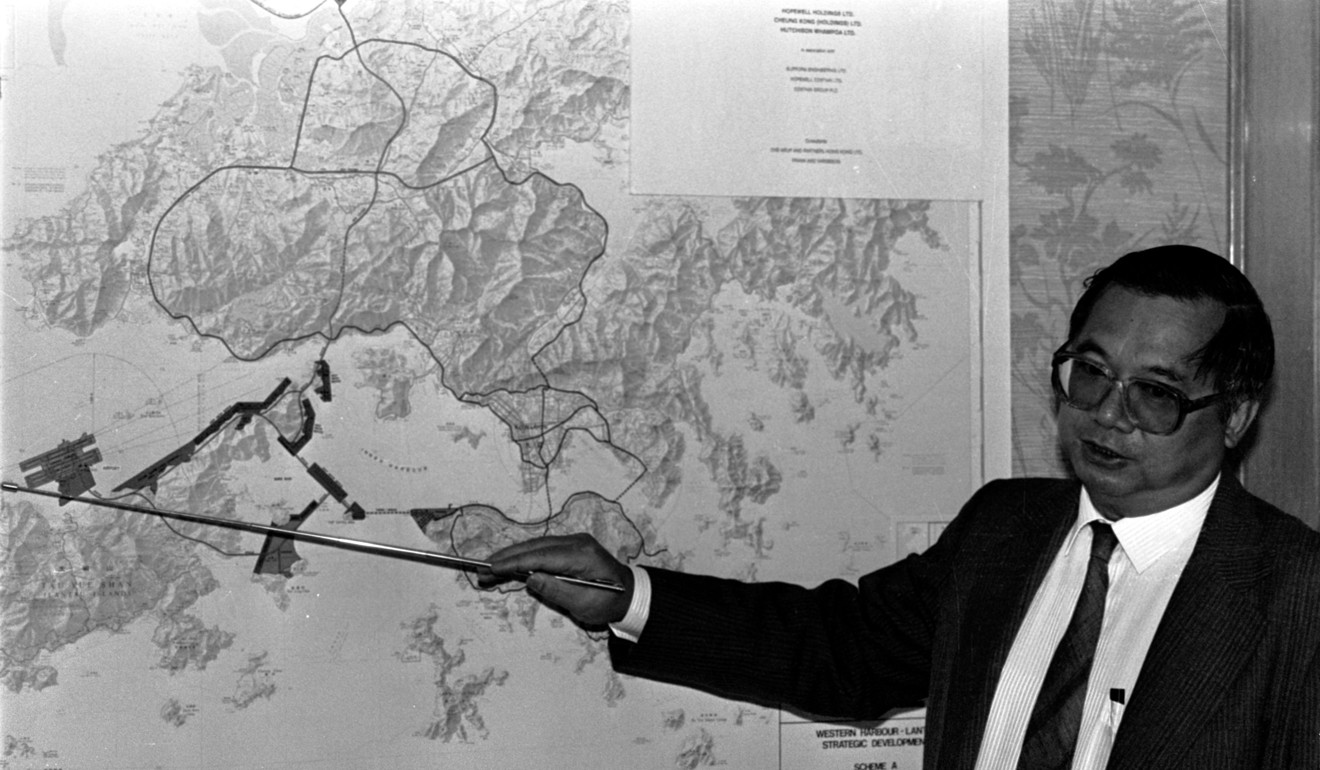

Wu’s many trips there led him to the idea of building a superhighway between Guangzhou and Shenzhen.

An engineering graduate of Princeton University in the United States, he believed a top-class road system would put development of the Pearl River Delta on the fast track.

But those were the mid 1980s, when most people could barely afford bicycles, and it was hard to get Guangdong officials on board.

When he asked for maps of the area, they told him all maps were considered state secrets. He found a way around that hurdle.

I was convinced that Hong Kong people wouldn’t have to emigrate if the mainland got rich gradually

He wanted to build a six- or eight-lane highway, but some officials criticised him for being extravagant. He settled on six lanes and entered a joint venture with Guangdong authorities to build the superhighway. But negotiations dragged on until the 1989 Tiananmen Square crackdown, when all projects ground to a halt.

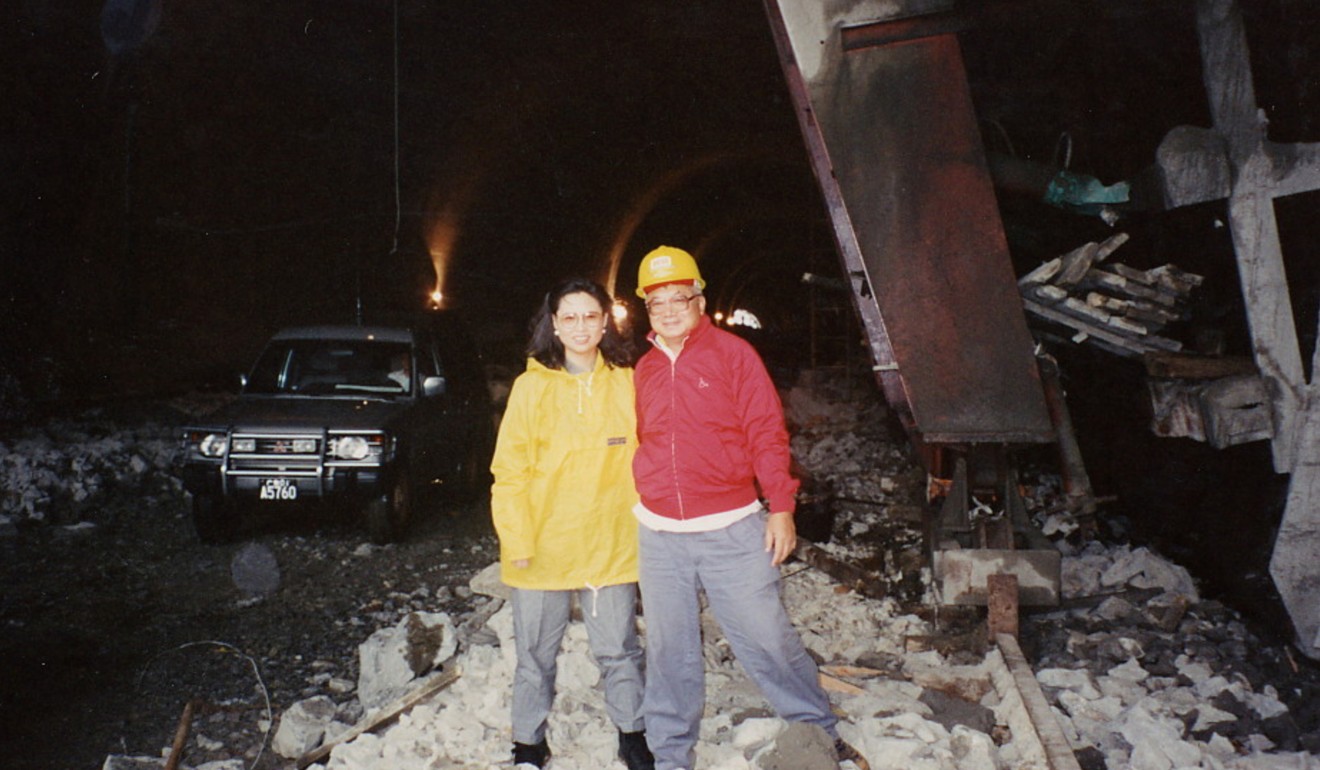

Construction of the 122.8km superhighway finally started in 1990 and was completed in 1994.

Much has changed in China since his early visits, but the tycoon, who turns 83 in December, said it would take a long time for the mainland to catch up in “software” areas such as the rule of law, academic freedom and protection of intellectual property.