Tung Chung: another Hong Kong district turned into a front line for anti-government protests

- Residents in the Lantau tourist and travel hub had been angry in recent years over the influx of mainland Chinese visitors

- Recent anti-government protests have brought disruption and a different kind of problem: no one wants to visit

When Tung Chung resident Mary Wong, 35, went to work at a restaurant at Hong Kong International Airport on September 1, she could scarcely imagine her usually unremarkable 30-minute trip home would turn into a two-hour walking nightmare.

But with her usual S64 bus suspended, along with Tung Chung and Airport Express trains, and road traffic in the district’s major thoroughfares brought to a standstill by anti-government protests, she had no choice but to join everyone else forced to trek the 5km or so to the town.

“By the time I got home after the long march, I was completely drained of energy and drenched in sweat. But I had to get home in time to cook and take care of my kids; otherwise I might have just slept on a bench at the airport and spared myself a lot of pain and sore muscles from the walk,” says the mother of two.

Known for its numerous nearby sights and attractions including Disneyland and the Ngong Ping 360 cable car, the once-buzzing tourist hub has turned into a virtual ghost town after three months of unrest, sparked by an extradition bill, which the government has since pledged to withdraw.

The bill, had it been passed, would have allowed transfers of criminal suspects to mainland China, among other jurisdictions, for trial. The government’s response, including what protesters describe as a belated commitment to formally retract it, has so far failed to placate them. Their demands have since expanded to include an independent inquiry into police conduct during protests, and fully democratic elections.

Following two weekends of what protesters called “stress tests” of airport infrastructure, which mostly consisted of blocking roads, they have threatened to return with a fresh test on Saturday.

Here we take a look at another Hong Kong district turned into a protest front line, and explain how the area and its residents have been affected.

What was Tung Chung known for before?

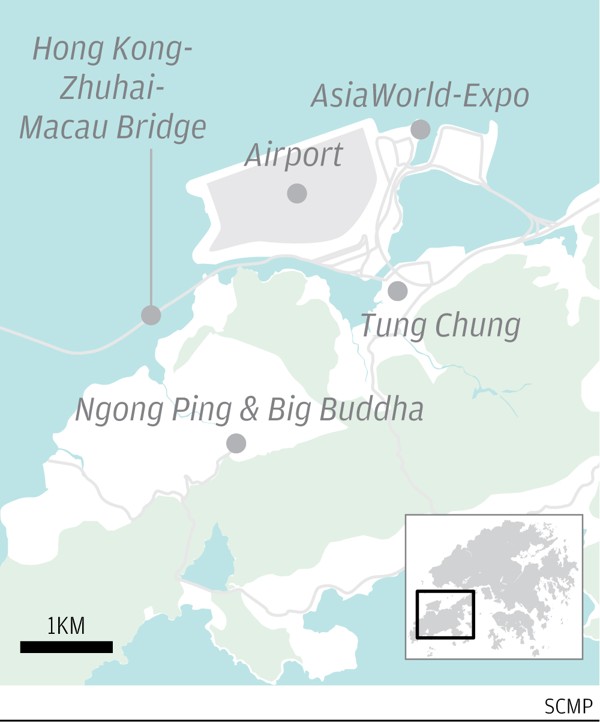

Tung Chung, meaning “eastern stream” in Cantonese, is on the northwestern coast of Lantau Island. Developed in the 1990s as a new town, the former fishing village was transformed into a transport gateway and tourist hub, connecting the city’s airport to the Kowloon peninsula via the Tsing Ma Bridge, and to Hong Kong Island by the Airport Express train line and the Tung Chung MTR line.

The Disneyland theme park and the cable cars taking tourists to sightseeing spots such as the Big Buddha and the nearby Po Lin Monastery have drawn millions of tourists.

The opening of the 55km Hong Kong-Zhuhai-Macau Bridge in October last year further cemented Tung Chung’s status as the city’s land-and-air gateway to mainland China.

How did residents react to the arrivals?

Local residents have complained about the transformation of their once-tranquil community into a border town rivalling Sheung Shui, a town in the northern New Territories popular with parallel traders and mainland tourists, its shops flooded with day trippers from across the border.

After the bridge opened in October last year, droves of mainland tour groups descended on Tung Chung. The following month, localist group Tung Chung Future staged a protest in a bid to “reclaim” the zone from the new arrivals, saying their influx had caused shortages of daily necessities like toothpaste and tissue paper and long queues at bus stops and restaurants, as well as noise and hygiene problems.

It’s almost like my hometown is serving tourists rather than residents, with shops selling high-end luxury products in the outlet mall, and public toilets becoming very dirty

Victor Yu Kim-man, a secondary school teacher who has lived in the area since 1997, says the community was changed beyond recognition.

“It’s almost like my hometown is serving tourists rather than residents, with shops selling high-end luxury products in the outlet mall, and public toilets becoming very dirty. On some days, I would rather stay at home or hang out with friends in other districts, to avoid the crowds in Tung Chung,” the 50-year-old says.

How have recent protests changed the area?

The extradition bill protests swung Tung Chung to another extreme, with mainland visitors staying away.

Tourist arrivals for the whole city slumped nearly 40 per cent year on year in August, the biggest such decline since the Sars outbreak of 2003, according to government figures. About 80 per cent of the city’s tourists are from mainland China.

The protests, now in their 14th week, have included actions at the airport which, as well as affecting nearby roads and trains, led to the closure of the facility and the cancellation of nearly 1,000 flights for two days in August. The usually packed Disneyland has been almost deserted.

For Wong, who works part-time as a waitress at a Western barbecue restaurant in the airport’s Terminal 2, these changes mean more than minor inconvenience.

“Business is bad at the restaurant now that tourist numbers have fallen sharply. I had my hours cut to five per day, down from the seven- or eight-hour shifts I used to work, so I now take home $4,000 (US$511) less per month,” she says.

“My colleagues, who are mostly Tung Chung residents like me, are all very worried about this sad state of affairs continuing, and how we are going to support our families with the reduced pay.”

To avoid traffic disruption again, Wong now gets to the airport an hour early, and has told her husband and two daughters to avoid staying out too late, in case clashes between police and protesters erupt suddenly.

Is anyone pleased by the reduced crowds?

Scars of protests remain. At Tung Chung station, which was among the heaviest casualties of radical protesters’ vandalism on September 1, turnstiles, LED monitors and other facilities are still smashed up.

Lau Wing-yin, 28, co-founder of the Tung Chung Concern Group, which railed against the changes to the area’s character, sees a silver lining amid the tourism slump.

“No more congestion everywhere; Tung Chung is returning to normal,” says Lau, who has lived on the nearby Fu Tung Estate with his mother and sister since 1997, as he takes a casual stroll around the district.

Relief for Tung Chung residents as mega bridge crowds ease

“Virtually all mainland tourists have disappeared since June. This square with the flowing fountain here outside the MTR station used to be jam-packed with tourists, now it’s empty. They used to sit on the steps here, eating bread or cup noodles and leaving a trail of rubbish behind.”

With the protests dragging on, Lau even anticipates an exodus of big brands in his local mall and the return of small neighbourhood stores. “As a resident, I would rather be able to buy some cheap stationery, than be surrounded by Louis Vuitton bags that I can’t afford. If property prices fall by 60 per cent because of the protests, I might even buy a flat and move out.”