Explainer | A century-old reservoir has captured Hongkongers’ imagination amid Covid-19 doom and gloom, political strife

- News of public discovery of grand underground structures which were nearly demolished causes government U-turn and apology

- The Post explores past conservation controversies and lists gems throughout city that history buffs can visit

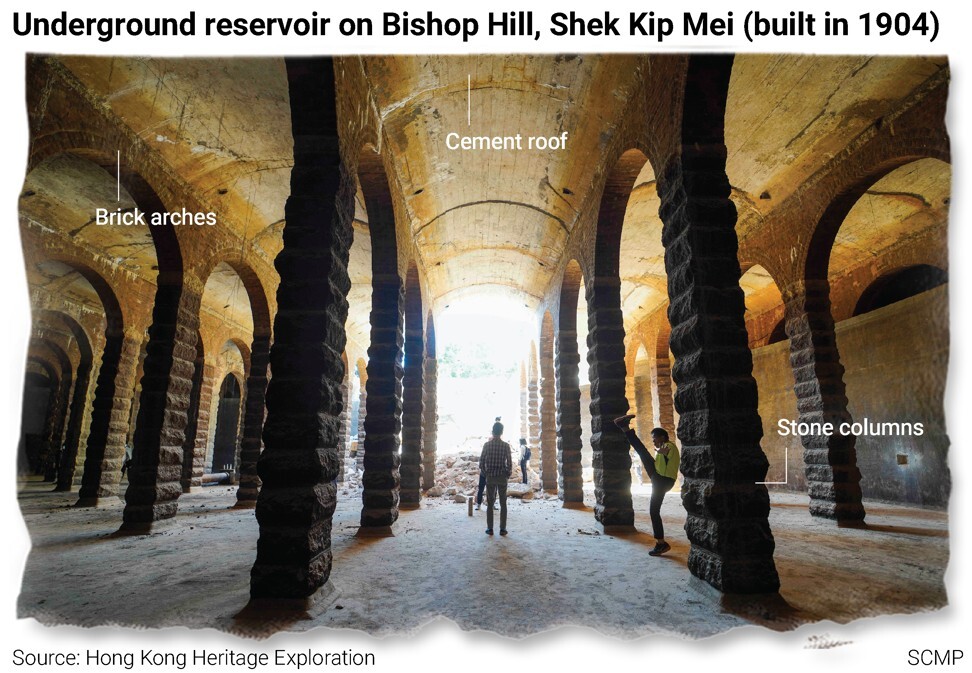

The discovery of a century-old underground reservoir with massive stone and brick arches in Hong Kong has been the talk of the town in a city weary from a year of headlines centred on the Covid-19 pandemic and political uncertainty.

The structure on a hilltop in Shek Kip Mei was initially destined for demolition, with parts already torn down, but public discovery of its historical significance set social media abuzz, forcing authorities to halt the work, issue an apology for “insensitivity and miscommunication”, and vow to look into preserving the site.

The Post explores the saga, reactions and the bigger heritage scene in the city.

Hong Kong authorities suspend demolition of century-old underground reservoir

1. What’s the origin story behind the reservoir?

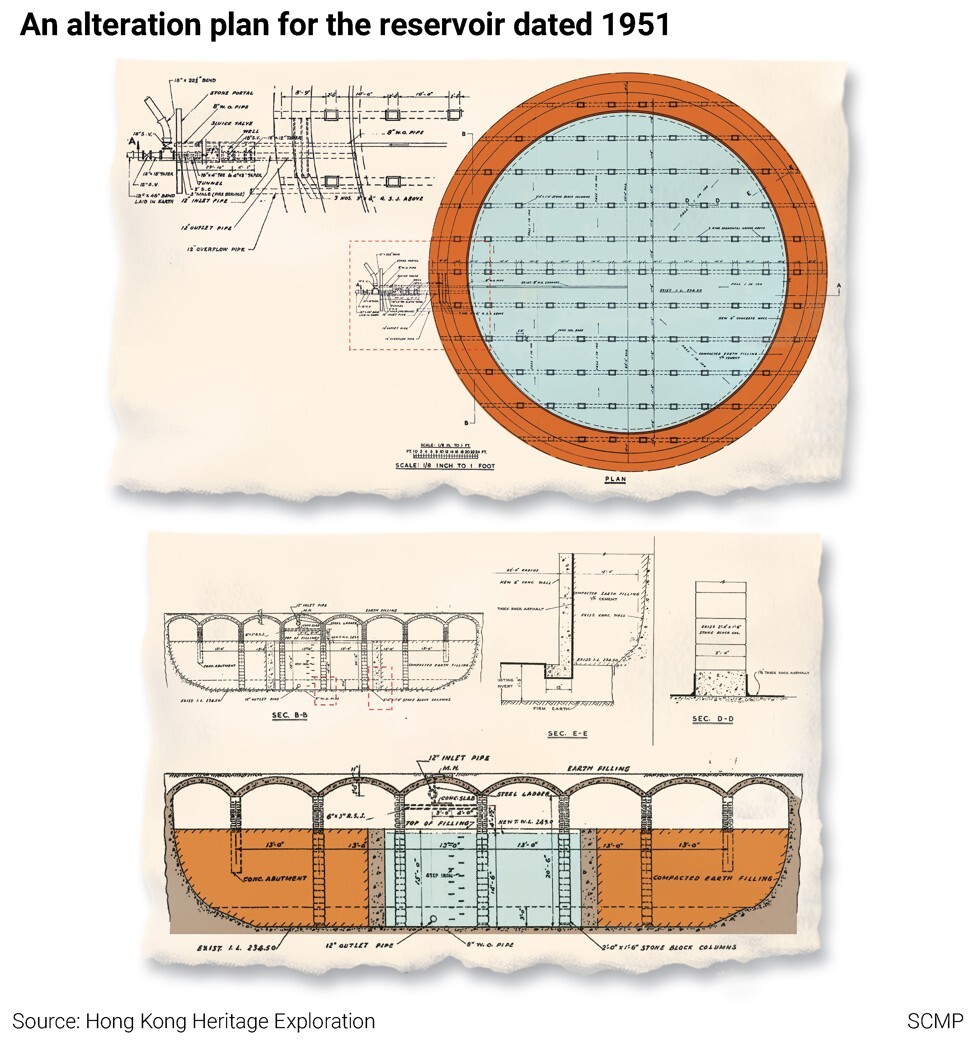

Located at what is known as Bishop’s Hill in Shek Kip Mei, the reservoir was built on August 10, 1904, as part of the Kowloon Waterworks Gravitation Scheme, according to old colonial documents. It was created to increase water supply for the Kowloon peninsula’s expanding population, after the first one in Yau Ma Tei was deemed inadequate. The British colonial government spent about HK$68,000 on the project at the time.

The round underground structure, built with 100 stone columns and brick arches, is 47 metres in diameter and 7 metres deep. It has not been used since the 1970s.

2 . Why do Hongkongers care so much?

The unique structure featuring striking arches has astounded many locals and experts, who did not expect that there would be a heritage site of this scale in the city.

Since Monday, history buffs and groups have dug up old documents from university archives sharing stories and drawings of the reservoir on social media.

But the government’s failure to preserve the site has angered many. Local historian Ko Tim-keung accused antiquities officials of unprofessionalism in agreeing to demolition works, given that information on the reservoir was so readily accessible.

The city’s gloomy outlook amid the pandemic and its murky political future might have fuelled sentiments, according to Simon Shen Xuhui, another former antiquities board member and an international relations scholar.

“2020 is a dreadful year … but before it has ended, such dramatic good news have emerged: this super heritage site at the centre of Hong Kong, bearing witness to top-class infrastructure and aesthetics in colonial times,” Shen wrote on Facebook.

He said the photos “reminded everyone of what Hong Kong was”.

3. What comparisons can be drawn from the architecture?

The construction technology of the service reservoir in Hong Kong harkens back to the Roman empire, according to Lee Ho-yin, director of the University of Hong Kong’s architectural conservation programmes. He also cited similar engineering feats at the Basilica Cistern in Istanbul, now a major tourist attraction.

Veteran architect Bernard Lim Wan-fung, a former member of the Antiquities Advisory Board, urged authorities to bestow the site monument status and for it to be converted into a place for the public to learn about the city’s water-resources history.

Lim pointed to the Paddington Reservoir in Sydney, Australia, which has been redeveloped into gardens with wide boardwalks accessible to the public.

4. How did the structure escape the attention of government officials?

From 1996 to 2000, the antiquities office conducted a citywide survey on buildings in Hong Kong built before 1950. Some 8,800 structures were recorded, and 1,444 of them, considered of higher value, were selected for a more in-depth survey in 2009. However, the service reservoir site was not on the list.

On Tuesday, it was revealed that heritage officials and engineers from the Water Supplies Department held a meeting in 2017 on the latter’s proposal to demolish the site for new land use. Heritage officials thought it was “just a normal tank” and concluded there was no need for further study, according to Commissioner for Heritage Ivanhoe Chang Chi-ho, who on Tuesday publicly apologised for the “lack of sensitivity and miscommunication”.

Chang said the decision was made based on “general information” available at the time, but did not elaborate on the documents examined at the meeting.

5. What are other past conservation controversies?

In 2007, dozens of activists staged a sit-in at the pier and gained widespread sympathy from the general public. They argued the site, built in the 1950s, was part of Hongkongers’ collective memory and an important public landmark. The development chief at the time – now city leader Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor – insisted the pier should make way for a bypass, but that it would be resurrected.

The bypass has been built, but the pier has not been relocated.

Just a month after Queen’s Pier was knocked down, the defacement of King Yin Lei, a private mansion in the Mid-Levels which had been featured in television shows, sparked outrage. The damage was done by the property’s owner.

The government quickly declared the site a provisional monument. In the end, the owner was granted land nearby for development, and surrendered the plot for preservation.

In 2014, the archaeological discovery of wells, drains, and thousands of artefacts dating back to the Song dynasty at the construction site of the Kowloon City rail station in To Kwa Wan caused a public divide. Some wanted the structures removed so the new railway could be built, but others argued the relics were evidence of a major human settlement. In the end, the MTR Corporation preserved part of the findings and will display them at the original location when the station is finished.

Head of heritage office sorry for ‘insensitivity’ over plan to demolish century-old site

6. What are other sites of historical interest that the public can visit?

There are plenty in Hong Kong. To name a few remarkable ones: Tai Kwun (the former Central Police Station revitalised by the Jockey Club as a culture and leisure complex); the Mills in Tsuen Wan (a factory turned into a cultural spot by owner Nan Fung Group), and PMQ on Hollywood Road, Central, which was a former police quarters redeveloped as an arts and retail site.

There are also more than a dozen public heritage sites across the city that have been revamped by NGOs with public funding, and these have been designated for various uses under a revitalisation scheme, including a news museum, a youth hostel and a Chinese medicine clinic.

7. What are other conservation projects?

Apart from the reservoir in Shek Kip Mei, officials on Tuesday said they would also start a study on four other pre-war underground reservoirs, located on the Peak, Mount Gough, Yau Ma Tei and the Mid-Levels.

Bernard Lim said it was also time for the Antiquities and Monuments Office to continue to look out for hidden gems throughout the city. “The stocktaking exercise was not meant to be exhaustive after those 1,444 sites were graded. Officials should keep on finding.”