Hong Kong’s teachers told to be on alert after suspected suicides among city’s children hits eight-year high

- Authorities urge educators to look out for warning signs including poor personal hygiene and changes in behaviour

- Guidelines also suggest paying close attention to attendance records and pupils’ coursework

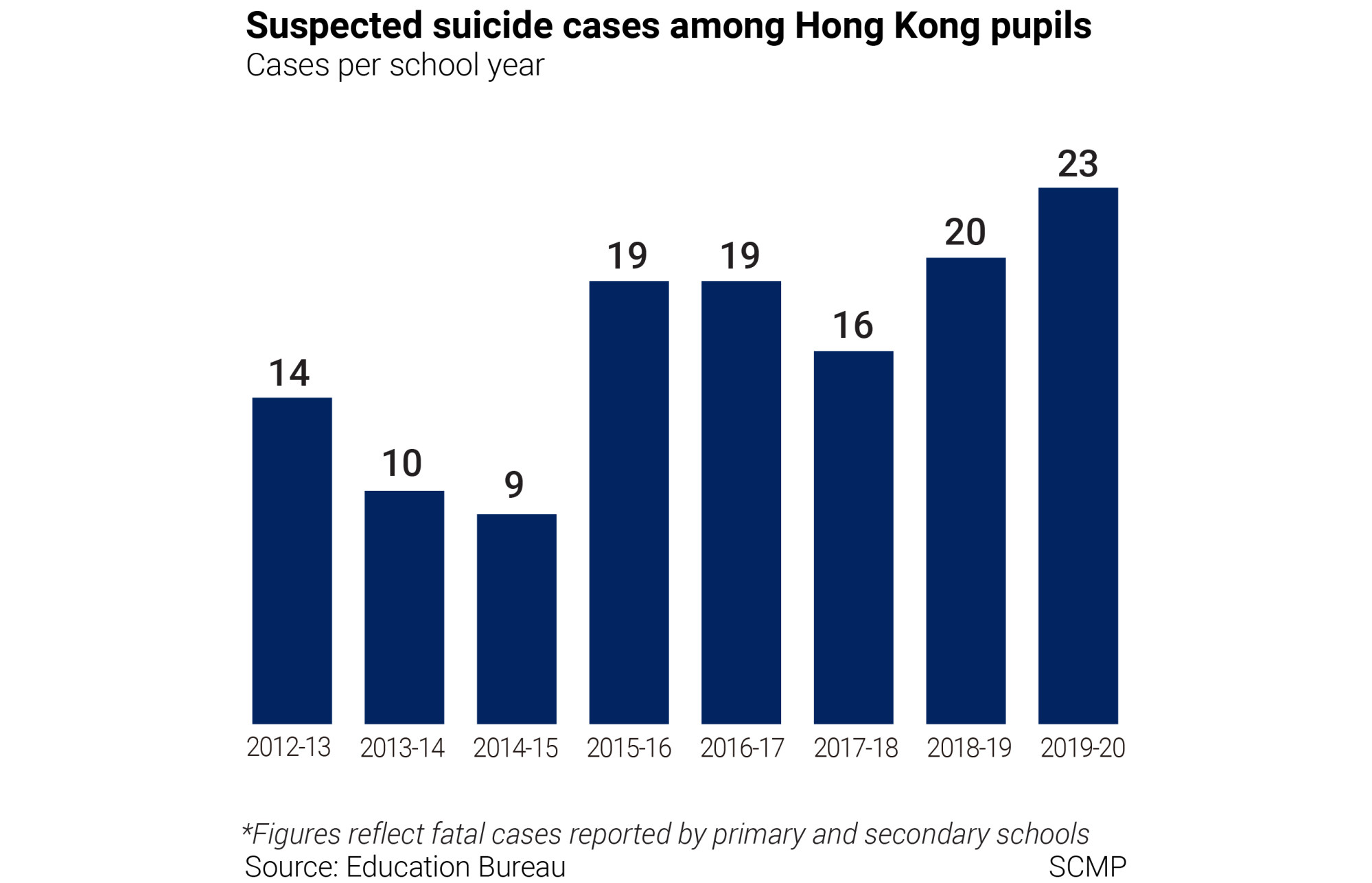

Official figures showed at least 23 primary and secondary pupils were suspected to have taken their own lives during the 2019-20 school year, up from 20 cases reported in 2018-19, and 16 in 2017-18. There have been about 130 cases since 2012, the first year records were available.

The number of children under the age of 18 seeking psychiatric services for depression at government facilities has also jumped over the past few years, with about 1,070 pupils requiring such services in 2019-20, compared with 450 in 2015-16.

They also urged education officials to provide more help and guidance to teachers to support pupils remotely, with online learning largely replacing face-to-face classes.

In a letter to primary and secondary school heads this month, the Education Bureau called the number of suspected suicide cases “regretful and disheartening”, and reminded schools to watch out for changes in pupils’ emotions from an early stage.

“Teachers should have the basic knowledge and skills to identify and support pupils who are at risk of suicide, while they should also pay more attention to pupils’ daily manners … in case there are abnormalities in their emotions and behaviour,” the letter said.

According to the bureau, teachers should look out for warning signs in the amount of time pupils are away from school, or any messages in their coursework. They should also be on the alert if a student suddenly did not pay attention to his or her personal hygiene, or continually appeared to be anxious or afraid, or were easily annoyed.

Happiness among Hong Kong children at five-year low, new survey finds

A reference video for educators suggests that signs could include pupils only eating “one meal per day because of a loss of appetite, or perhaps not taking showers or having messy hair”. Other signs might be when a child says “they feel their existence causes trouble to others and feel that [life] is meaningless”.

Citing figures published by the government’s Child Fatality Review Panel in 2015, it said more than 74 per cent of children who killed themselves had expressed suicidal thoughts, including verbal warnings, before they did so.

Secondary school principal Li Kin-man said while educators had been doing their best to identify students with emotional issues, the suspension of in-person classes during the pandemic meant more challenges for teachers.

“Pupils are also trying to adapt to this new normal, when [regular social life] and meeting up is not always an option. Teachers also have been working very hard [to support students],” said Li, who is vice-chairman of the Hong Kong Association for School Discipline and Counselling Teachers.

He said if pupils were not turning on their cameras during online lessons, or even if they were at school but wearing masks, it would be difficult for teachers to notice their facial expressions or behavioural change.

“One thing that is missing from the bureau’s latest reminder is how teachers can support pupils and identify [warning signs] amid a lack of opportunities to meet them face-to-face amid the pandemic. For example, can that be done through virtual meeting sessions?”

Professor Paul Yip Siu-fai, founding director of the University of Hong Kong’s Centre for Suicide Research and Prevention, said teachers, like social workers and doctors, play an important role as a gatekeeper in identifying pupils’ suicidal behaviour. He said for students who lacked family support at home, peer support at school during in-person sessions was especially important.

If you are having suicidal thoughts, or you know someone who is, help is available. For Hong Kong, dial +852 2896 0000 for The Samaritans or +852 2382 0000 for Suicide Prevention Services. In the US, call The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline on +1 800 273 8255. For a list of other nations’ helplines, see this page.