Hong Kong ex-residents look back on former home more than a year since launch of BN(O) scheme, share stories of strained ties, bittersweet feeling

- Families recall how they left loved ones behind last year and how they maintain old relationships while forging new ones in adopted home

- Hongkongers who have had their visas approve number 97,057 since the scheme launched on January 31 last year

Ivy Cheung has yet to resolve a rift with her mother, whom she left behind in Hong Kong after the family took the momentous step of moving to Britain last August.

“One of our big concerns was I worried about my boys, because I don’t know what the red line set by the Hong Kong government is,” she said.

While she and her mother still speak on the phone, their relationship is strained.

“Even now, from time to time, I will talk with her to let her know more about my position so she can understand my decision or try to stand in my position, but I always lose,” she said.

Majority of Hongkongers with BN(O) visas in UK won’t come back, survey finds

The Cheung family is among 97,057 Hongkongers who have had their BN(O) visas approved since the scheme launched on January 31 last year, out of 103,900 applications. While some such as the Cheungs have split up, with parents and children leaving behind grandparents, others decided to stick together and bring over three generations to start over in Britain.

Adjusting to their new lives has not always been easy, with residents forced to come to terms with differences in food, communicating and other societal norms, but the new arrivals are determined to keep their identity and culture alive.

Families divided

Ahead of Hong Kong’s return to Chinese rule in 1997, colonial ruler Britain granted the city’s residents born before the handover BN(O) passports that allowed them to stay in the country for up to six months. An estimated 5.4 million of Hong Kong’s 7.4 million residents are eligible for the visas, which allows holders and their dependants to live, work and study in the country for up to five years, after which they can apply for citizenship.

The British government created the special pathway to citizenship after the imposition of the national security law, which Beijing said was needed to stamp out threats of secession, subversion, terrorism and collusion with foreign forces, but critics say was merely a pretext to wipe out dissident voices following the unprecedented political upheaval.

When Cheung told her mother, 71, she was moving to Britain with her husband Johnny, 57, her two sons, 18-year-old Terry and 23-year-old Matthew, an argument erupted. Her mother did not fully trust the intentions of the British government in granting the visas, she said. At first Cheung tried to convince her mother to join them, but gave up after too many heated exchanges. One bone of contention was Cheung’s decision to sell their flat in Kowloon, which her mother insisted the family would need when they came back to visit.

“She is from the old generation, and says: ‘I am your mother, You need to follow. I am right’,” she recalled.

They still speak and her mother often sends the family packages of food from home, but Cheung said she had given up trying to convince the older woman on why the family needed to leave Hong Kong. Anything to do with politics or the government is quickly glossed over between them, and some details of the family’s new life is not shared openly. When Cheung’s son Terry contracted Covid-19, the parents chose not to tell the matriarch. He was asymptomatic and eventually recovered.

Britain to change BN(O) visa scheme to allow younger Hongkongers to apply

Adding to the family strain was Terry’s reluctance to leave behind his friends and grandmother, whose cooking he loved. He begged them to allow him to stay.

But his parents were adamantly against the idea, with his mother telling him: “We are the same family, four people in the same boat. We need to leave together.”

Terry finally relented but his resentment lingered and according to his mother, he rarely spoke to his father during their first month in their new home.

“I was angry, because I don’t have a choice,” Terry said. “I wanted to stay in Hong Kong because I don’t know anything about the UK.”

While Matthew adjusted to the move easily as he spent three years at university in Lancaster, Terry found it difficult to integrate into a new social circle after his parents dropped him off at Cardiff University last September. On his first night his flatmates invited him out clubbing, entertainment that he and his friends back home viewed as appealing only to “bad” eggs.

“Clubbing the first few times, I didn’t really like it because I think it’s so noisy and it’s packed,” Terry said, admitting he had since grown more comfortable.

Missing Hong Kong and especially speaking Cantonese, he applied for a part-time job at a shop selling bubble tea, a concoction made with chewy tapioca pearls and which became wildly popular in Asia before catching on in the rest of the world. The shop owner, also a Hong Kong transplant, agreed to hire him and Terry met a young woman who had also left the city with her family under the BN(O) scheme.

“I was really happy to find someone who also comes from Hong Kong,” the teenager said. “She understands Hong Kong and what it’s like and what you’re going through.”

While finding love helped him get used to life there, both he and his girlfriend hope to return to their original homes one day, he added.

“I miss my friends and the food. I still think I’m a foreigner in the UK. I want to live in a place that belongs to me,” he said.

His mother said she could accept his decision to move back when he was older, but for now, the family must stick together.

“I really hope he can fully understand our decision-making. I know he is homesick and likes Hong Kong life, because Hong Kong life is too simple. In the UK, everything is just a little bit more difficult, right?” she said.

Single and lonely

Steve* moved to London in September 2020 after taking part in the anti-government protests in 2019. The 37-year-old made plans to leave almost as soon as the national security law was enacted in June the following year. He lives in a single room in a house in East London owned by a mainland Chinese family who converted the three bedroom unit into a six bedroom place.

After working as a waiter, Steve landed a job at an estate agency, whose clients are mostly Hong Kong residents with BN(O) visas, work that was more in line with his previous employment in the property sector. He earned about £22,000 (HK$227,000) a year, and paid £580 a month for his room, he said, adding that while he could now afford around £700 a month, he had not been able to find anything suitable.

“That’s a lot and my salary is not high here. £700 is my limit.”

Steve bemoaned missing out on many important family events, such as the birth of his niece last November. He did not know when he would see his sister or parents again as he had no plans to return to Hong Kong.

His father, a 69-year-old retired civil servant who supported the government and Beijing, did not support his decision to leave. The family’s WhatsApp group, which is filled with pictures of his new niece, is the extent of his contact with his parents.

While Steve said he has adapted to his new life, he often felt lonely and when he could afford it he treated himself to Japanese food or a movie to cheer himself up.

“Outside Asia, I don’t think you can find a city that is as thriving or as exciting as Hong Kong,” he said. “I would say it’s maybe a bit quiet and a bit boring here.”

Steve had met two other Hongkongers through a WhatsApp group, a hairdresser and that person’s girlfriend. He hoped to meet a partner himself, thinking the relationship might help him better settle into life in London: “I have been thinking of going on dating apps,” he said.

‘Third of Hongkongers with BN(O) status weighing UK move, 6 per cent acted on it’

For Bella*, 25, and Peter*, 29, their monthly gatherings with other Hongkongers in Manchester are bittersweet events. They said they avoided discussing the situation back home for anything longer than a few minutes and the group instead focused on playing board games or singing karaoke, while sharing information about their new life in Britain.

“We cannot ignore the news in Hong Kong because we are still concerned about it, but we avoid thinking too much as it makes us depressed,” Bella said.

While they talked about the coronavirus epidemic and politics, they kept the conversations brief because they hoped to have fun and not a “sad time”, she said,

“It is not the Hong Kong that we know, but everything that has happened is predictable, ‘’ she said. “We knew that it would happen, it was just a matter of time.”

Bella has remained close with her family in Hong Kong and she speaks via video calls to her parents, brother, sister and grandparents at least once a week. During Lunar New Year in February, the family set up a group dinner with everyone on FaceTime so they could feel like they were together.

Her father texted and called her often, which could be annoying, Bella said, with a laugh.

“I know my dad misses me so much,” she said. “Emotionally, of course he wants me to stay with him, but he knows that the reality is it’s better to stay in the UK.”

Together and hopeful

When Michael, 34, and his wife decided to move to Britain with their two-year-old son, they asked his parents to go with them but they refused. While the national security law was part of the reason for uprooting, the couple decided to leave mostly so their son would have a better education, he said.

They held off from making the jump for a year so they could sell his two-bedroom flat in Tseung Kwan O last October for HK$6 million and he could continue drawing a salary as an IT worker, Michael said.

While they were waiting, Michael’s sister, her husband and son decided to pack up for Birmingham, he revealed. He joked she was the “explorer of the family”, who reported back on the quality of the local schools and overall standard of living, information that cemented their decision to move.

Confronted with the fact that their children and grandchildren were heading overseas, Michael’s parents finally agreed to join them in Britain, he said.

While Michael expressed concerns about the cultural differences his parents faced, he said they made daily trips to the supermarket and the family was helping them improve their limited English.

When the children have homework about British history, they include their grandparents in the learning, he said.

Michael recounted recently meeting another family who had also brought the grandparents with them, and already his mother had set up a date to play mahjong.

“As long as they are staying with us, everything is fine. The family can overcome anything as long as we are together,” he said.

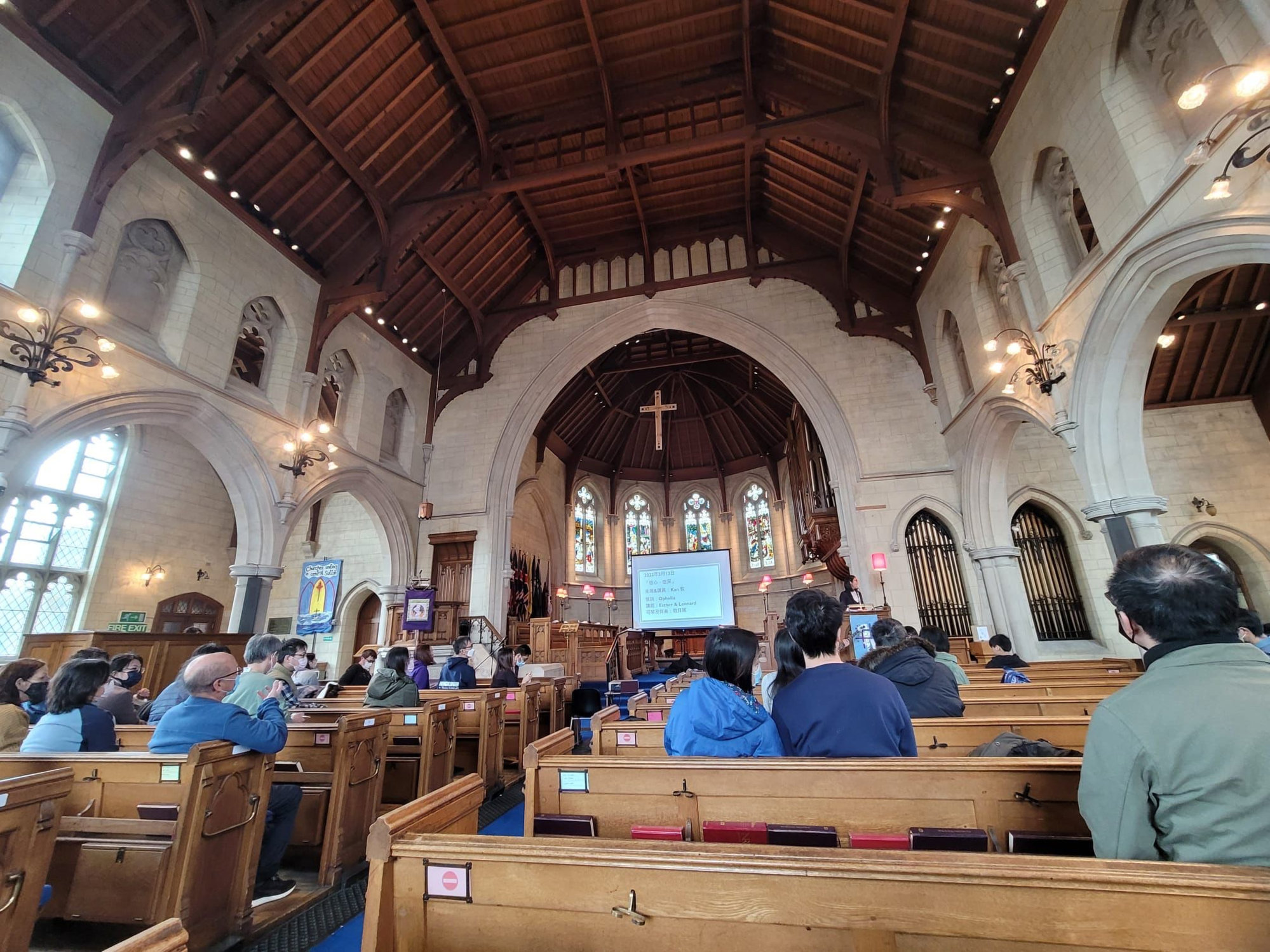

Church-based community

One place where many Hong Kong migrants have been coming together is churches, both ones that operate in English as well as Chinese. Many have turned to UKHK, launched in February by Krish Kandiah, which draws on a network of 650 churches to assist arrivals from Hong Kong, navigate basic aspects of society, such as education, job hunting, finding a family doctor and using public transport.

Kandiah said he believed Chinese-language churches were now the fastest-growing ones in the country. Cantonese-speaking congregations have contributed to one church in Manchester quadrupling its regular attendees of 200 attendees, while another in Reading has seen its flock expand from 70 to 300. In Birmingham, Britain’s second-largest city and a popular choice for migrants, the number of attendees at one church doubled to 600, and even in the north of the country in Hull, a priest saw his flock grow from 60 to 100.

An English-language majority church in a town in Hampshire welcomed 60 arrivals from Hong Kong with T-shirts that said “fun ying”, which is Cantonese for “welcome”.

Reverend Kan Yu, who moved from Hong Kong to England 20 years ago, is a Methodist minister based in southwest London. She helped found a fellowship group called the Sutton Hongkongers Fellowship, which is affiliated with Trinity Church in Sutton. The organisation first existed online as a way for arrivals to get to know each other and they finally held a meeting in a park last June.

The fellowship is run by volunteers and while its more than 250 members are all from Hong Kong, Yu said they integrated with local churches, with some members attending Trinity Church in Sutton, where natives offered conversational English-language classes to the arrivals.

As an immigrant herself, Yu knows all too well the challenges of starting over in a new country. The fellowship offered the immigrants a way to share their language, culture, and emotions, she said. While the majority of the members were couples with children, some attendees were single parents who had left their spouse in Hong Kong due to different views on the future of Hong Kong and understanding of China, she revealed.

Yu, who is married with two sons, recalled the difficulties she faced as a new arrival, and said she believed that integration was not about assimilating but about sharing food, language and other cultural ties with locals. She cited an example of a newcomer who had started selling egg tarts, popular at dim sum restaurants and cha chaan teng.

“The question is about what do you want to let go? What do you want to keep as your identity?” she said. “We have our Chinese heritage and at the same time we are living in the UK. It is a special identity.”

*Names changed at interviewees’ request