Goodbye ‘Little Thailand’? Kowloon City’s Thai community in Hong Kong reflects on changes to way of life as redevelopment looms

- HK$15 billion redevelopment scheme by the Urban Renewal Authority will affect 1,600 households and 140 shops in the area

- Kowloon City is home to dozens of Thai restaurants and grocery stores frequented by Hongkongers seeking authentic cuisine

Warayutha Sridadet could not be prouder of a snack shop in Kowloon City run by his family, with the place having become a popular meeting spot for fellow Thais in the neighbourhood and beyond.

Almost every evening, his parents will hang out with friends at the doorstep of the shop on Nam Kok Road, sitting on stools placed on the pavement, chatting and drinking Thai beer. Though some community members, including from his family, have moved out of the neighbourhood, they still see the place as their second home.

“My parents are happier in Kowloon City because they can chat with old friends … My mum knows almost every Thai person here,” the 21-year-old Sridadet said. “They are now worried whether the shop can remain [after redevelopment].”

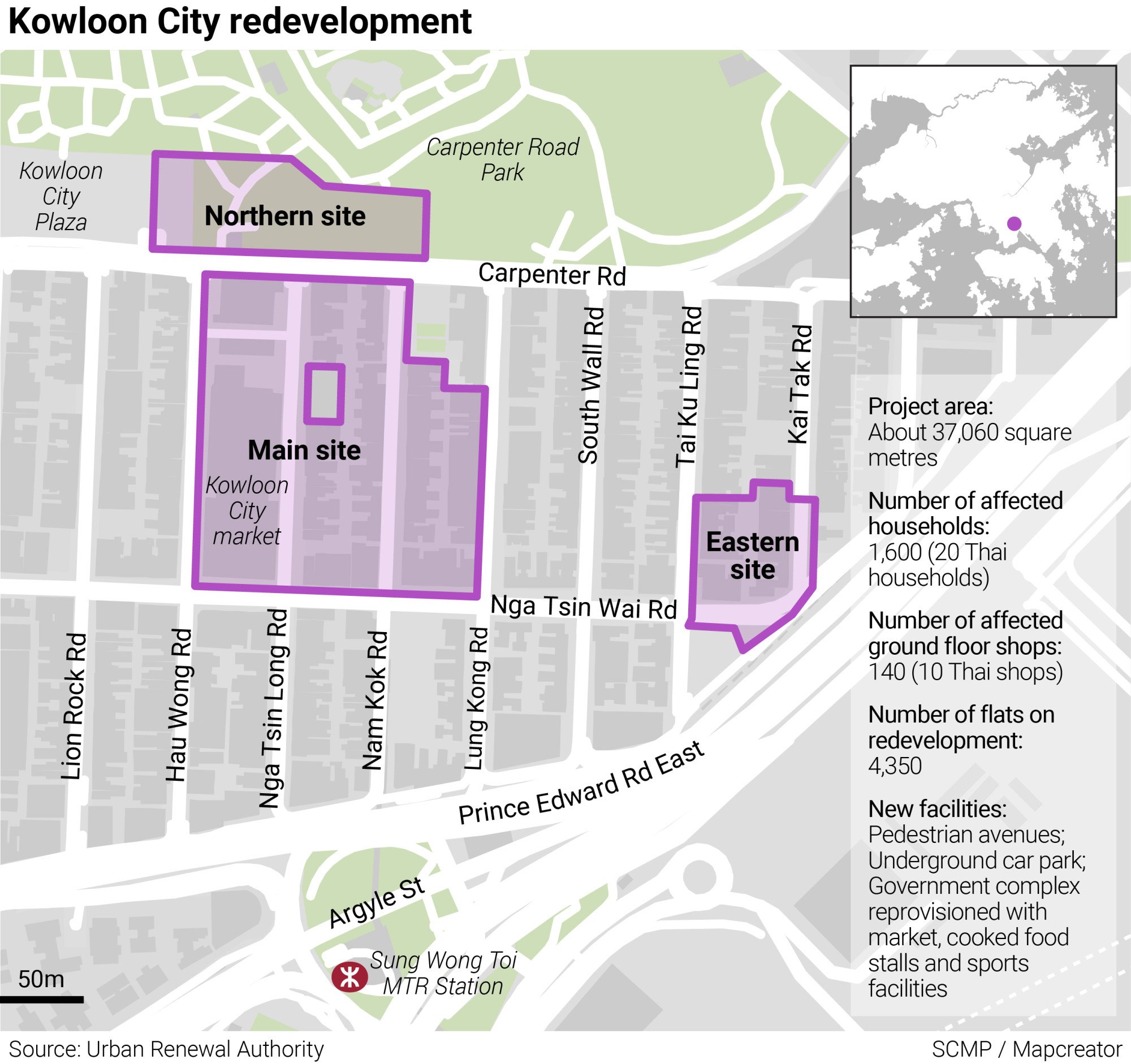

Sridadet’s shop is included under a latest project by the Urban Renewal Authority (URA) to give a facelift to the area between Carpenter Road and Nga Tsin Wai Road. The HK$15 billion (US$1.9 billion) redevelopment scheme, the second-largest project by the authority, will affect 1,600 households and 140 shops, yielding 4,350 flats by 2037, as well as repair old buildings around the site.

While the authority said it would try to work out ways to retain local character in the area, some Thais who spoke to the Post held mixed feelings.

Hong Kong renewal project to create more than 4,000 flats in Kowloon City

“We don’t even know if there will be a Thai community by then,” Sridadet said. “The rent may be over our budget and we are not sure if there will be a small-sized shop. A snack shop doesn’t need that much space.”

Kowloon City, nicknamed “Little Thailand”, is home to dozens of Thai restaurants and grocery stores frequented by Hongkongers seeking authentic cuisine. The community grew in the 1970s when Chiu Chow men and women they had married in Thailand came to settle in the area.

A version of Songkran, the country’s traditional water festival, was hosted by the community there to celebrate the Thai new year. According to a government census in 2016, more than 800 of Hong Kong’s 10,215 Thai residents live in the district.

Many Thais have moved in and out of Kowloon City over the years as the area underwent gradual transformation after the Kai Tak airport nearby was demolished in 1998, triggering patchy private redevelopments.

Sridadet’s parents, for example, lived there since 2000 and opened a shop for massage and haircuts nine years later. In 2013, they left for Sham Shui Po to run a Thai restaurant, and moved to public housing in Wong Tai Sin. Two years ago, they returned to Kowloon City to do business, selling mango sticky rice, Thai shrimp chips and traditional beverages such as grass jelly drinks.

The family might consider relocating the shop back to Sham Shui Po since the rent in Kowloon City has been rising with the opening of a railway station a year ago.

Others, like 64-year-old Malison Waewkrathok, feel both happy and sad about having to leave.

Before retirement, Waewkrathok was a waitress in well-known local Thai restaurant Wong Chun Chun after working as a domestic helper.

To her, the district was not just her workplace, but also where she found comfort in shopping for ingredients for home cooking such as Thai soy sauce, pepper, lemongrass and lime.

“I like Kowloon City a lot,” she said, “Even when my friend in Tuen Mun invited me for a sleepover, I missed my home so much. I didn’t even want to stay there for one more night.”

This is despite Waewkrathok facing constant leaks in her toilet and makeshift kitchen in a 200 sq ft subdivided flat she shares with her elder daughter and two granddaughters.

“We are happy to move to public housing [with a better living environment],” she said. “It’s still a pity to leave Kowloon City, but not a pity to leave our flat.”

Hong Kong’s Thai community look back at five decades in the city

Some of Waewkrathok’s Thai neighbours have already left under the URA’s first and previous project in Kowloon City two years ago. Next to the current project’s eastern site, buildings between Kai Tak Road and Sa Po Road will be redeveloped into 810 private flats with an underground plaza and a public car park.

Penpaka Lee, 49, a Thai pastor who worked in a local church for 15 years, moved out to To Kwa Wan under the previous project but continues to serve the community in Kowloon City as she wants to help fellow countrymen bridge the language gaps she had faced when she first arrived 30 years ago as a domestic helper.

“I didn’t know how to speak or listen to Chinese,” Lee said. “Now I know a little bit more, I want to help as much as I can.”

She noticed that the Thai community in Kowloon City had continued to grow as parents brought their children and relatives to Hong Kong after settling down. Those who left due to redevelopments still returned on weekends for food and to meet friends and send money home, she said.

Lee added that the core Thai community in Kowloon City were shop owners on South Wall Road, hosts of the water festival. That stretch is not covered by the two URA projects.

“If there is another redevelopment in future making [these core Thai shops] go, they may not organise the activities again,” she said.

According to the URA, a survey launched since the end of May has so far identified 20 Thai households and 10 Thai shop operators in the current project area.

Eligible residential tenants will be compensated with public housing or cash allowances.

The URA will also rebuild a municipal services building housing a wet market and cooked food centre, but part of Carpenter Road Park will be carved up for the new complex.

Sukulporn Paipha, 55, who has run a Thai restaurant for more than 20 years in the municipal services building, said she looked forward to relocation because the building was “too old and broken” with concrete spalling from the roof. On rainy days, water would leak from the ceiling onto her dining tables.

Yet, Paipha feared redevelopment would further break up the Thai community as residents would not be able to rent costly private flats.

She has seen staff members leaving the district for public housing in Sham Shui Po, Lai Chi Kwok and even Tung Chung without returning.

“We were very happy back then. We sang karaoke and went drinking after work,” Paipha said. “Now they have disappeared.”

‘Little Thailand’ renewal plan leaves Hongkongers torn over losing community ties

The URA has said that to retain cultural characteristics of the Thai and Chiu Chow communities, pedestrian avenues at Nga Tsin Long Road and Nam Kok Road would provide more space for street shops, and the new market square would allow for room to host the water festival.

In a reply to the Post on Friday, it added that it would consider providing arrangements to retain local speciality stores and giving rental priority to Thai restaurants, similar to those in the previous Kowloon City project. It will also come up with proposals to help shop tenants in interim operations and relocations.

It cited a “successful” precedent in the Graham Street project in Central, where it had helped some fresh food stalls return to the site by setting up a temporary market during construction.

Professor Ng Mee-kam, director of the urban studies programme at Chinese University, said discounted rents would help retain the outgoing Thai shops. She also suggested building rental housing with simpler designs and lower costs for residents to come back.

“The URA acknowledges that people in the district can cultivate some characteristics,” Ng said. “But based on the market mechanism, without any special policy, they can hardly go back there upon redevelopment.”

Ng said the statutory body could bear more social responsibility in coming redevelopment plans to sustain the community and allow residents in need to stay in the district.

“They are not parasites, they engage in economic activities, which bring characteristics to the area. It is a win-win situation,” the scholar noted.