Wealth gap between Hong Kong’s crazy rich, miserably poor widens since handover

- Top 10 per cent earn 40 times more than bottom 10 per cent who are struggling to make ends meet as gap widens because of mix of reasons

- Experts call for more government intervention to help poor ‘who face hardship on all fronts’

Looking around his cramped home, with his family’s possessions piled up to save space, Chan Chuen-bui, 71, recalled that life was not this hard in his younger days.

The Hongkonger, who worked in interior furnishing, said he used to earn between HK$20,000 and HK$30,000 a month in 1997, and lived in a 300 sq ft low-cost public housing flat in Kwai Chung, paying about HK$1,000 a month.

“Jobs were not difficult to come by and as long as you worked hard, you could feed yourself well,” he said. “But that is not the case any more.”

Given a potent mix of reasons, from globalisation to government policy to high housing prices, Hong Kong’s wealth disparity has widened since the city returned to Chinese rule in 1997. The end outcome has been that poor people such as Chan find it tougher to get by despite working hard.

At the other end of the social spectrum, the city’s wealthy have grown richer, with incomes dozens of times more than what the poorest earn.

Chan said there was less furnishing work to do after 1997, especially since soaring home prices put an end to average income earners’ plans to buy flats.

Chan, who moved out of his public housing flat when he and his ex-wife divorced, saw his income drop from HK$1,200 a day to less than HK$900, until he stopped working because of glaucoma.

His current 50-year-old wife earns HK$15,000 a month working six days a week in a dried seafood shop. The couple and their 12-year-old daughter squeeze into a 100 sq ft subdivided flat in Sham Shui Po, one of the city’s poorest districts, paying a monthly rent of HK$4,000.

Chan said he sometimes skipped meals to save money for their daughter’s tutorial classes. Their only hope is that the girl will have a better life.

“Hong Kong has become a place where poor people like me find it increasingly difficult to get by,” he said.

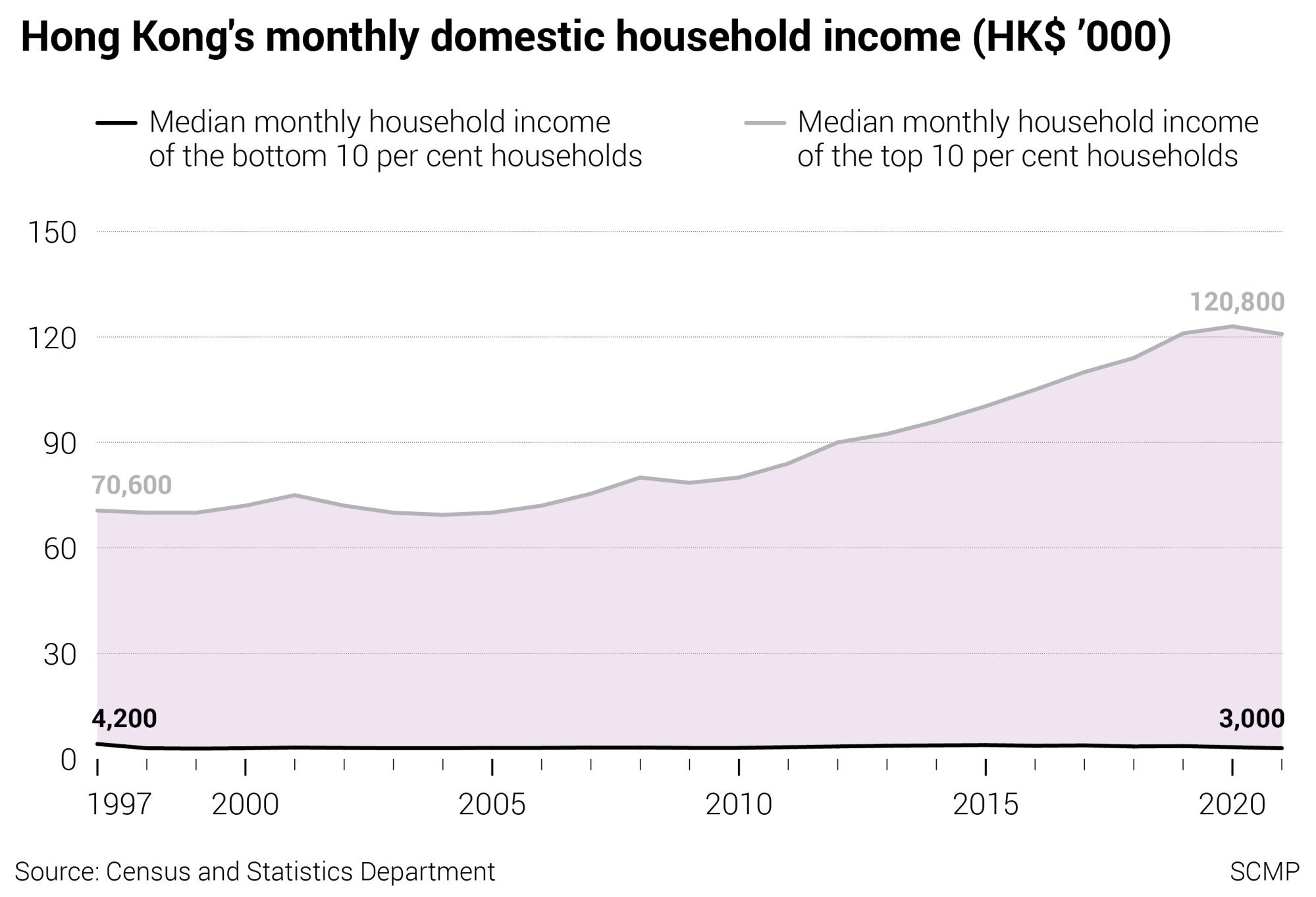

Official statistics show that in 1997, the median monthly household income of the top 10 per cent of households stood at HK$70,600, about 17 times that of the bottom 10 per cent, at HK$4,200.

Last year, the top 10 per cent earned 40 times more than the bottom 10 per cent. The income of the top 10 per cent jumped by 71 per cent to HK$120,800, while the bottom 10 per cent saw their income shrink by 29 per cent to HK$3,000.

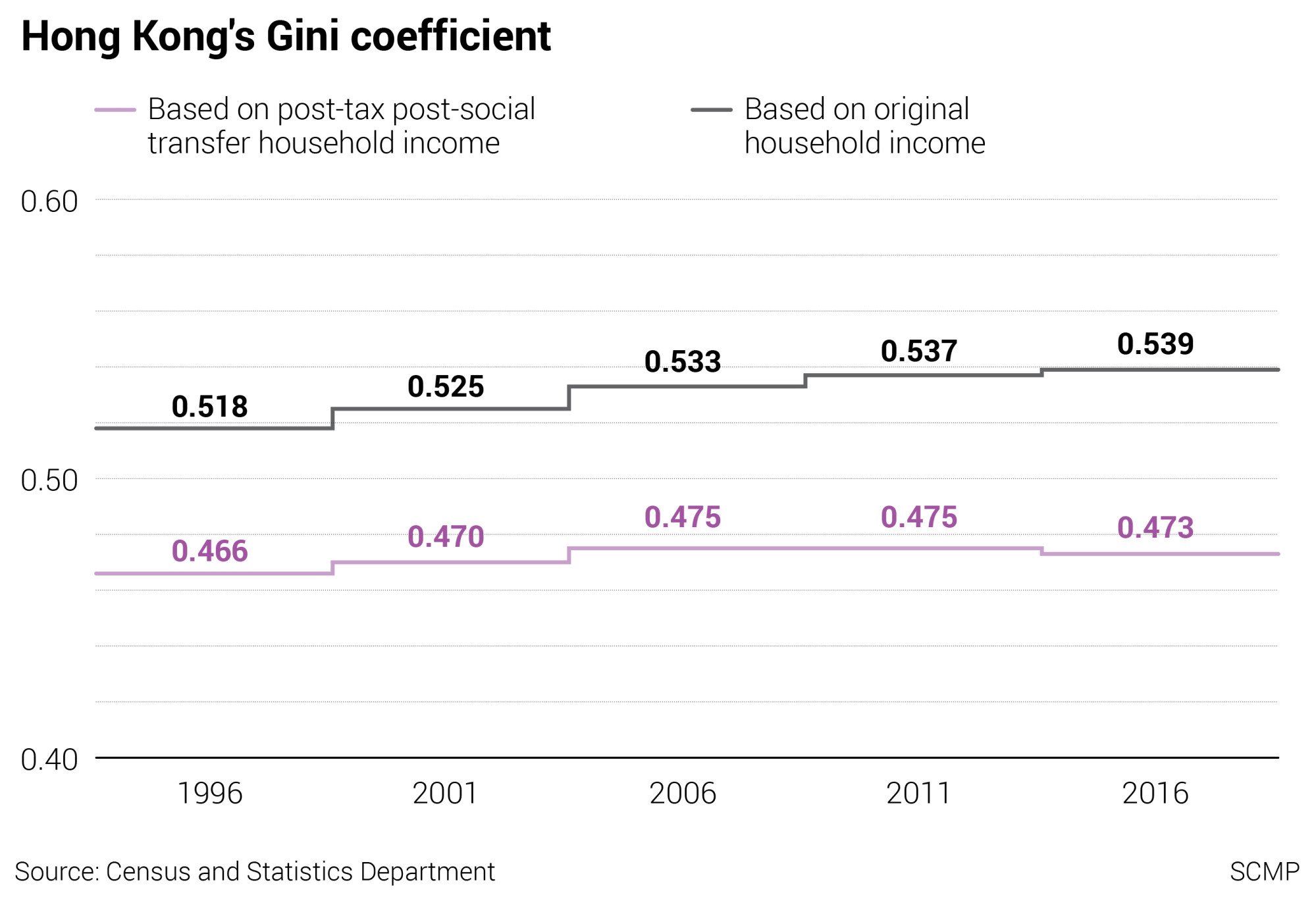

Based on original monthly household income, Hong Kong’s Gini coefficient, an index on how evenly income is distributed, rose from 0.518 in 1996 to 0.539 in 2016, the latest data available. Measured on a scale of zero to one, zero indicates equality and a coefficient above 0.5 indicates considerable disparity.

Economists and sociologists said the widening income inequality started before the 1997 handover, and it had since plateaued with a stable increase.

Aside from the income gap, they blamed multiple factors for the continuously widening wealth disparity. These included skyrocketing home prices, the government’s limited intervention, the huge influx of money into the city’s property and stock markets and economic disruptions from crises such as the ongoing coronavirus pandemic.

“Internal and external factors have all, together, led to the widening wealth gap,” said Dr Xu Duoduo, an assistant professor of sociology at the University of Hong Kong (HKU).

“Hong Kong has become the rich people’s Hong Kong. If the government maintains the status quo and makes no changes, the wealth inequality will only become worse, until it reaches a breaking point and leads to crisis.”

Hong Kong poverty rate hits 12-year high in 2020, government figures show

Multiple factors contribute to widening wealth gap

Xu said a turning point occurred in the 1980s, when the city transformed its economic structure from one focused on manufacturing to non-manufacturing activities.

From those years onwards, globalisation became an important driver of income inequality and Hong Kong was not immune from its effects, with jobs lost along the way.

Wealth started accumulating in the finance, property and insurance sectors, while manufacturing workers lost their jobs or flowed to low-income employment such as catering and cleaning.

“The income of truck drivers used to be very decent in the past,” she said. “But the transformation of the industrial structure led to the polarisation of jobs, and the widening of income inequality.”

In Hong Kong, the world’s least affordable housing market, skyrocketing home prices also played a significant role in widening the wealth disparity, experts said.

Call to help poor Hongkongers cut off from families on mainland China

Professor Terence Chong Tai-leung, of Chinese University’s department of economics, said home prices soared in the years after the severe acute respiratory syndrome (Sars) epidemic of 2003, when an influx of mainland Chinese pushed up property prices.

Those who owned property saw their wealth surge, whereas those who could not afford their own home not only did not benefit from rising property prices, but also faced higher rents and consumer prices.

Chong said quantitative easing – buying financial assets to inject money into an economy – in the United States since the 2008 global financial crisis had widened the city’s wealth gap further, with large amounts of money entering the Hong Kong market, pushing up home and stock prices.

The US had repeatedly resorted to this monetary policy, including during the pandemic, he said.

On the other hand, low-income workers faced a higher unemployment rate during the pandemic, especially those in construction, retail and catering, while high-paid jobs such as those in finance remained stable.

Chong said wealth inequality was not unique to Hong Kong and also existed elsewhere, including on the mainland, as a result of rapid economic development.

“The wealth gap will remain, but whether it will continue widening depends on what the government will do,” he said.

‘Too little government intervention’

Over the years, different city leaders had pledged to do more to tackle poverty but the results have not impressed many. Last August, Secretary for Labour and Welfare Law Chi-kwong said in a blog that Hong Kong’s wealth disparity was “an indisputable fact” and among the world’s worst.

He said the government had tried to narrow it through income distribution – by introducing a minimum wage of HK$28 per hour in 2011, which was raised to HK$37.50 in 2019 – and redistribution through taxation and social transfers.

He added the social transfers achieved more, with public housing the most effective, followed by the Comprehensive Social Security Assistance for those in financial need, Old Age Living Allowance for the elderly, and Working Family Allowance for low-income working households.

But HKU’s Xu said the intervention was too little, given the city’s post-intervention Gini coefficient remained at a high level of 0.473 in 2016.

She said many did not know the help was available, or were put off by complicated application procedures.

She said the government’s low social welfare expenditure and Hong Kong’s low income tax, with a standard rate of 15 per cent for the highly paid, had limited the government’s ability to redistribute wealth.

“The Hong Kong government has long stuck to ‘small government, big market’ and simply maintained very basic welfare,” she said.

Wealth disparity leads to intergenerational poverty

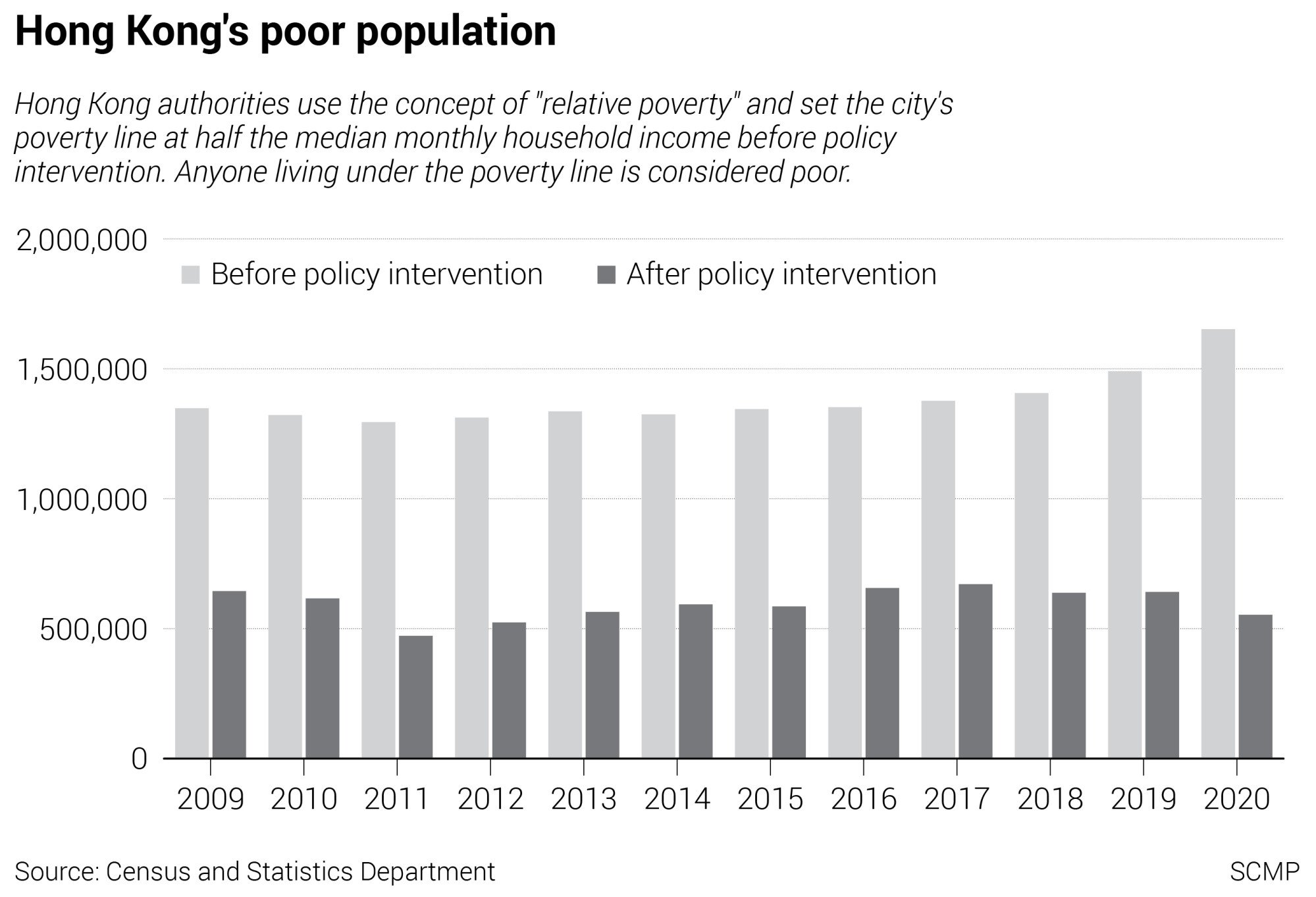

According to the Hong Kong Poverty Situation Report 2020 released last November, 1.65 million people, or 23.6 per cent of the city’s total population, lived below the poverty line, set at half the median monthly household income. That means nearly one in four Hongkongers was poor.

The poor population grew by 22 per cent from 1.35 million in 2009. Poverty statistics before 2009 are not available.

Sze Lai-shan, deputy director of local NGO the Society for Community Organisation, said the life of low-income residents had become more difficult since the handover.

Those struggling hardest included the elderly, low-income working families, and new migrants from the mainland.

Sze, a social worker of 27 years, said they faced hardship on all fronts, from unstable jobs and low wages, to surging home prices and rents, and having to live in the city’s worst housing – tiny subdivided flats that were home to more than 220,000 residents.

Unlike the wealthy, the impoverished could not afford computers, internet access, tutorial and interest classes or overseas trips for their children’s education. They had to wait for a long time for treatment in public hospitals.

Wong Shek-hung, director of the Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan programme of Oxfam Hong Kong, a local NGO dedicated to fighting poverty, said the widening wealth gap led to intergenerational poverty.

“When a city’s wealth disparity keeps widening, the poorest, despite how hard they work, do not have enough resources to improve their lives and move up the social ladder,” she said. “One thing leads to another. The poor may never break out of poverty.”

Hong Kong may use luxury Fanling golf site to build 12,000 public housing flats

Big changes needed to reverse trend

Wong said the ideal was for the low-income majority to enjoy the fruits of the city’s economic development like the well-off to “improve and prosper together”.

While the minimum wage helped eradicate extremely low pay for some workers – toilet cleaners, for example, used to receive only HK$7 an hour – she called for it to be raised, to catch up with rising inflation and help poor workers meet their basic living needs.

She also urged the government to set up an unemployment insurance scheme, lower the threshold for financial help so that more would benefit, and speed up building more public rental housing and transitional housing for the poor.

HKU’s Xu said the government should abolish its “small government, big market” mindset and intervene more, including by raising taxes for the richest, and establishing long-term social security and welfare policies, including a universal retirement protection system.

Incoming city leader John Lee Ka-chiu has pledged a “result-oriented” approach to governance, promising to tackle “pressing livelihood issues” and the welfare sector is watching anxiously.

Anthony Wong Kin-wai, business director of the Hong Kong Council of Social Service, said the city needed a clear plan to reduce poverty and to mobilise the resources needed to achieve it.

On a broader level, he said as the city’s industrial structure was partly responsible for the widening wealth gap, Hong Kong should not rely too much on industries such as tourism, finance and logistics, but drive the development of other sectors to create more high-income jobs.

He conceded that making these changes could affect the city’s position as a financial hub, but said: “If they can succeed in reversing the wealth gap trend, it will be worth it.”