Newspaper backlash signals unpopularity of China’s divorce cooling-off period rule

- The newspaper pointed to data that 38 per cent of divorce applications do not follow through with the divorce after 30 days

- But people online said the new law is an infringement on personal freedoms

Over three months after it went into effect, China’s newly instated cooling-off period for divorces remains unpopular among large swathes of society, as proven by the fierce backlash a local newspaper received for trying to defend the measure.

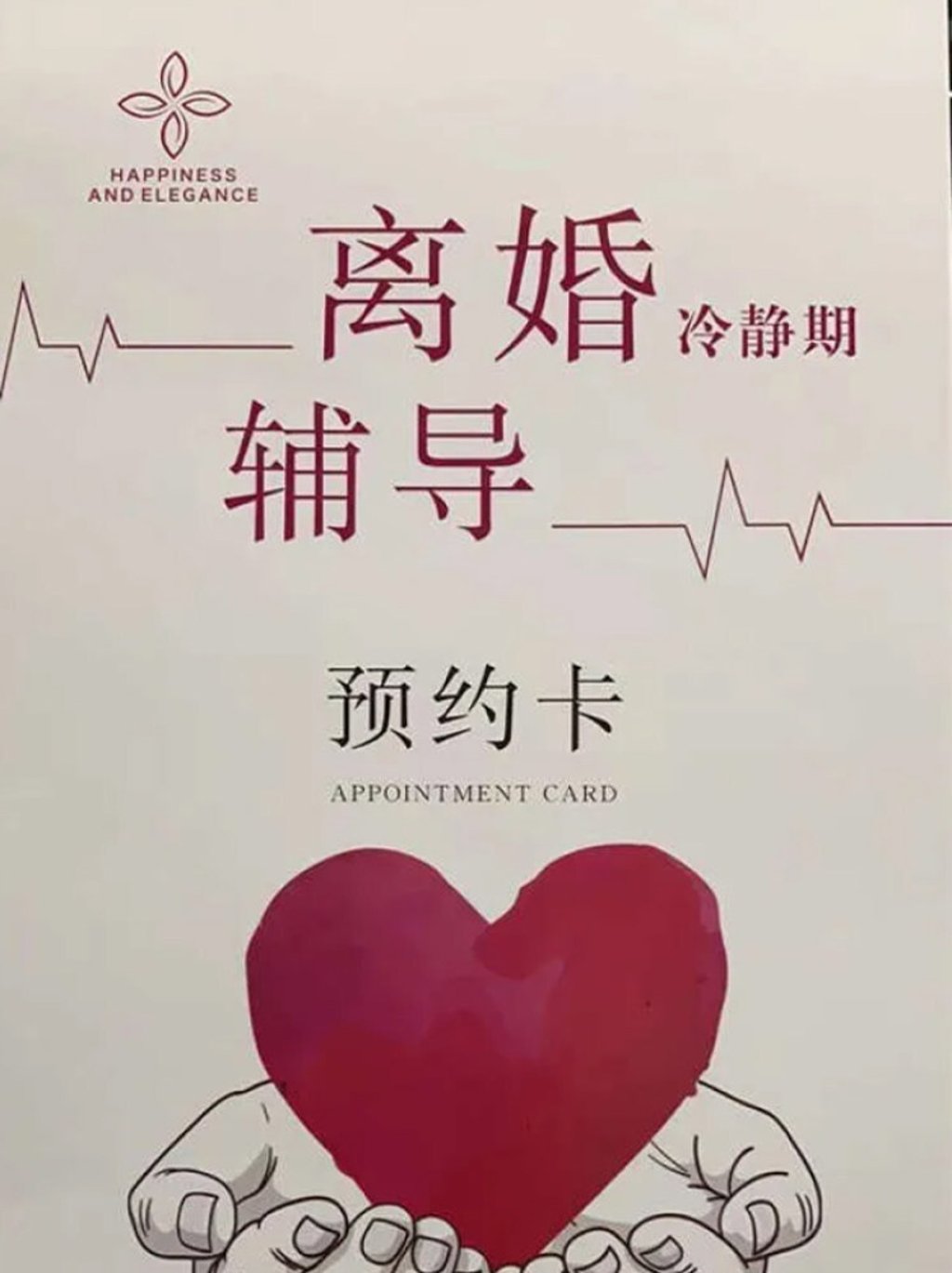

In an article on Tuesday, the Hangzhou Daily, which covers the city of Hangzhou in eastern China’s Zhejiang province, tried to prove that the cooling-off period effectively prevented impulsive divorces. The law, which went into effect on January 1, 2021, requires couples to wait 30 days after filing for a divorce to “rethink” their decision. After that period, they must return to the civil affairs department to finalise the divorce.

The report claims that data from Hangzhou showed 832 out of 2,186 couples, or 38 per cent, who initially applied for divorce either retracted their applications or did not show up for the final approval.

The article was met with fierce backlash online, with many people saying the new law infringes on individual freedom.

“2,186 cancer patients walked into the hospital, after being briefed on treatment cost, 832 patients never showed up again. Apparently, a high medical fee can help cure cancer,” said a comment receiving the most “likes” on Weibo, China’s Twitter-like service.

“What we really need is a ‘cooling-off period’ before marriage, instead of before divorce, so people can avoid getting married impulsively,” another said.