China’s censors increasingly play the part of morality police with the conservative values of 1950s America, experts say

- LGBT people, gender fluidity, feminism and female sexuality are increasingly in the sights of China’s censors as much as political dissent

- Experts describe the moral preoccupations of authorities as similar to the moral panic of 1950s middle class American society

In its crackdown on popular culture and LGBT people, feminists and other groups, China’s approach has come to increasingly resemble the values of 1950s America, say its critics.

However, censorship of pop culture has been expanding in China for some time. The publication of China’s 14th five-year plan last year which included culture was a noticeable turning point, according to Professor Michel Hockx, the director of Liu Institute for Asia and Asian Studies at the University of Notre Dame in the US.

“If previously the emphasis in policy towards popular culture was mainly to allow it to develop as a market sector that generated economic revenue and created jobs, the emphasis now is on ‘putting social benefits first’,” Hockx told the South China Morning Post.

Back to the 1950s: ‘won't somebody think of the children’

In recent years Beijing has become increasingly concerned that popular entertainment on streaming platforms is spreading views and ideas that run counter to traditional ideals of masculinity and femininity and encouraging new gender identities and forms of sexual expression.

Hockx said this approach had parallels with the moral values of 1950s America. “The definition of what is ‘healthy’ is quite conservative, similar to US popular culture of the 1950s or so. No sex, clearly defined gender roles and strong patriotism,” he said.

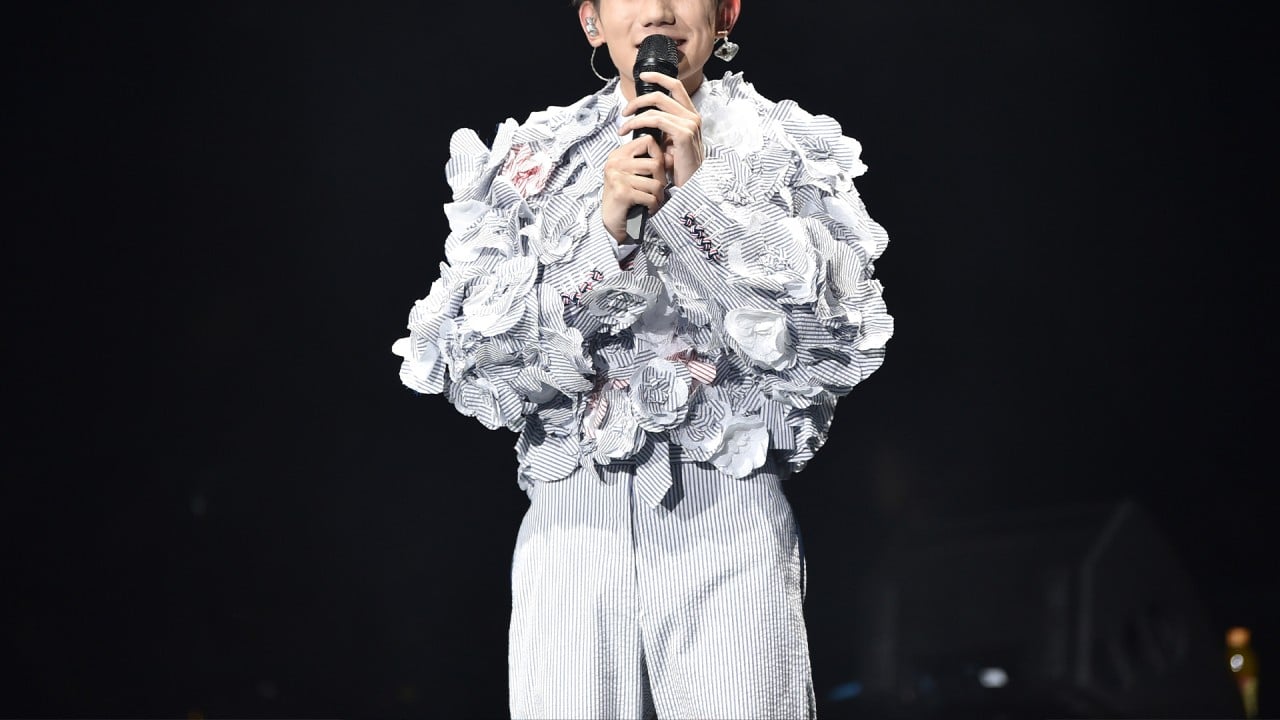

Has China’s push to ban ‘effeminate’ men claimed its first victim?

However, according to Chinese screenwriter Wang Hailin, gay love is sickening and promoting it is tantamount to committing a crime.

“While China still lacks sex education, influencing the young ones, whose sexual awareness has yet to be fully developed, with such culture is, to some extent, a crime,” he said.

Dr Hongwei Bao, Associate Professor in Media Studies at the University of Nottingham in the UK, said censorship was often justified in the name of protecting children from “harmful” influences in a country without a well-developed media classification system.

“The frequent reference to children and young people’s physical and mental health is symptomatic of the expansion of the middle-class population and value in Chinese society,” he told the Post.

China moves to kill romantic gay-themed ‘boys’ love’

Pop culture versus political censorship

Political censorship, such as the case of Oscar-winning director Chloe Zhao, has always been a given in China, but increasingly there is a widening of the censorship from concerns about graphic sex and violence to include a wide range of social behaviour.

The crackdown on pop culture has followed the same “top-down, heavy-handed” approach to political dissent, said Angeli Datt, senior research analyst for China with US-based human rights group Freedom House.

“The Chinese Communist Party increasingly views LGBT and feminist issues as ‘Western values’ and that individuals, who use rights-based language, as being ‘foreign forces’,” she told the Post.

“This approach is also seen through nationalistic, often state-backed, netizens who have trolled feminists and led to university LGBT society social media accounts being shut down last year.”

Senior researcher on China for Human Rights Watch Yaqiu Wang said the Chinese government’s interpretation of acceptable content had widened from politically sensitive content to anything that violates “moral codes”.

China’s LGBT community caught up in Xi Jinping’s widening crackdowns

“What is considered ‘good’ is becoming increasingly narrowly defined, it is no longer just about not challenging the Communist Party’s rule or criticising the government, it now has to promote the Party’s nationalistic, sexist and heteronormative values,” she told the Post.

Professor Lu Peng from the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences said beyond the content itself, authorities are also increasingly concerned by China’s zealous fandom culture.

“If the popularity of some shows has led to bad social behaviour, then it’s correct to seek a solution,” he said.

Power of tech platforms and fear over loss of control

As online streaming sites and social media platforms drastically changed the media landscape in China, tech companies which are often the producers and distributors of such content are increasingly playing the role of de facto censors.

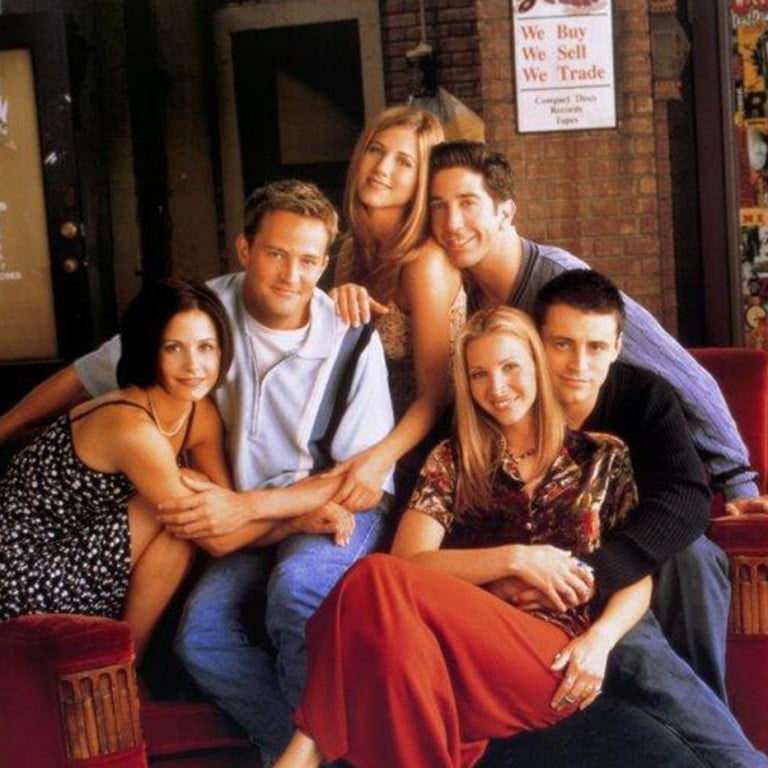

While the Fight Club case may appear on its surface to be a win for consumers against overzealous censorship by company Tencent, that is not necessarily the full picture, argues Bao.

“China’s video-streaming platforms must find a good balance among the political pressure from the Chinese government, the economic pressure from global media companies, demands from its consumers and users, these companies’ brand names and PR strategies, and so on,” he said.

Hockx said changes to the government’s approach in recent years have shown that consumer power in China is decreasing and that the government is more willing to intervene in popular culture.

“The Fight Club example shows that there is still wiggle room and that unprompted, overcautious, and clearly silly censorship decisions by certain companies can be effectively challenged by consumers.”

“However, the government is now actively seeking to exercise more control and willing to sacrifice economic benefit in doing so,” Hockx said.

A request for comment from China’s media regulator, the National Radio and Television Administration (NRTA), did not receive a response.