Where light pollution impacts marine life most – new global atlas highlights areas of concern

- Scientists have mapped coastal cities and their contributions to light pollution affecting the oceans, to pinpoint hotspots for research into its impacts

- LED lights are a major factor behind the increase in light pollution in cities such as Hong Kong, but it’s a fixable problem, they and other experts say

People who spend a lifetime in cities like Hong Kong, Shanghai or Beijing might not be able to see the Milky Way with the naked eye during the course of their lives.

For example, the American city of Philadelphia had a wake-up call in October 2020 when a major “collision event” resulted in the deaths of hundreds of birds because they were disoriented by poor weather and drawn to the city by the night lights, where they then flew into buildings, killing themselves.

While scientists continue to study the impact of light pollution on the skies, we know remarkably little about how artificial lights impact marine wildlife, which is a problematic gap in our knowledge because today’s cities are very likely to be built near large bodies of water.

The one notable exception is sea turtles, where scientists have shown light pollution disrupts their nesting habits.

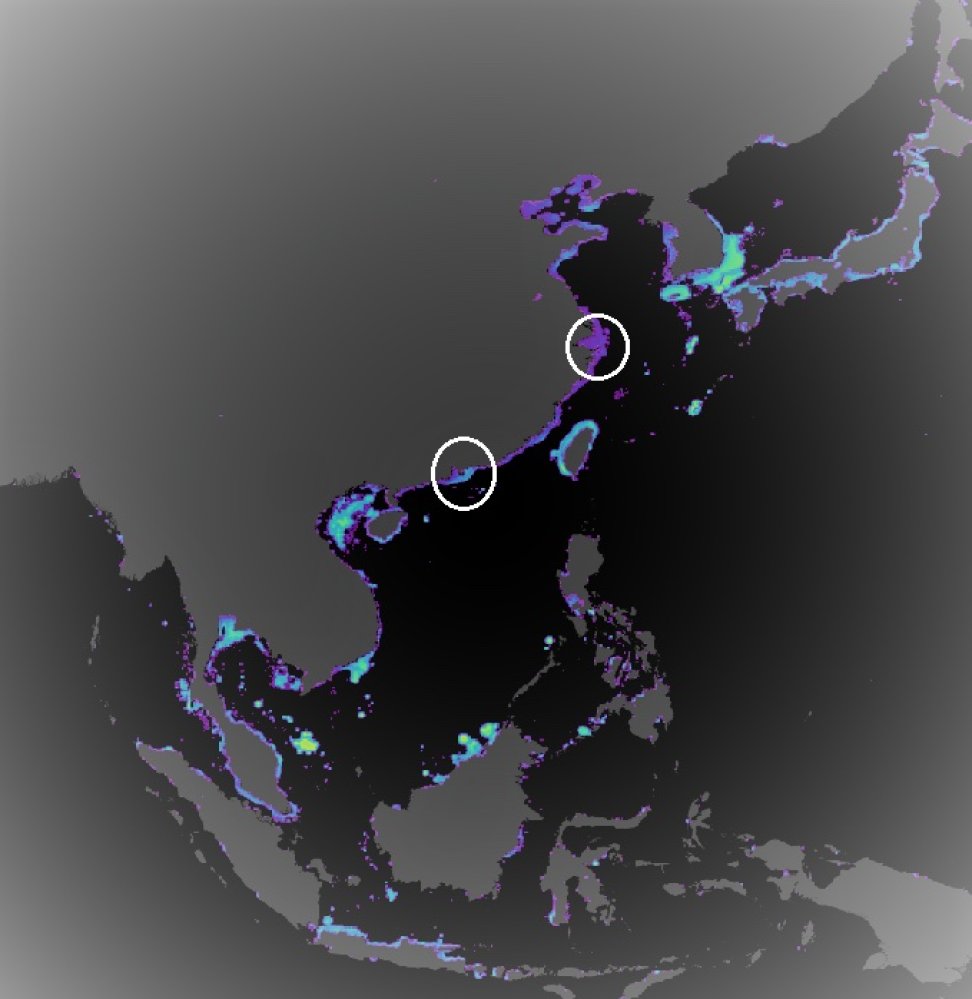

In mid-December last year, a team of scientists from the UK and Israel took early remedial steps by publishing a “global atlas of light pollution” in the University of California Press that shows where our lights penetrate the oceans.

Call for action as rising temperatures hit poorest Hongkongers hard

“Eight of the top 10 megacities, globally, are coastal, and they are rapidly expanding. There is a ribbon development along the coastline that is critical for [the impact of light pollution] because you distribute your light across a great expanse,” said Tim Smyth, the head of science for marine biogeochemistry and observations at the Plymouth Marine Laboratory and co-author of the map.

By building a model around zooplankton, which are simultaneously sensitive to light and essential to marine ecosystems, they created a map allowing them and other scientists to pinpoint hotspots where marine life might be particularly vulnerable.

David McKee, another author of the study and a physicist from the University of Strathclyde in Scotland, said: “What you are seeing is a growing realisation that the light we are emitting is eating into the environment and the potential impact is unknown at the moment.

“What we are hoping is this atlas is a way to identify where the impact is most likely to be significant.”

The study found that many of the top emitters of artificial light are in East Asia and Southeast Asia.

As those regions continue to urbanise, one problem has emerged as a significant contributor to light pollution: LED lights.

Jason Pun, a principal lecturer at the Department of Physics at the University of Hong Kong, whose work includes monitoring light pollution, explained the reason for this.

“[The proliferation of LED lights] is an issue that has been lost in the conversation because this is a once-in-a-generation global shift. It’s growing extremely fast, and almost all of the newly installed lights are LED.”

LED lights emit a pronounced blue colour, and blue light scatters more easily in the atmosphere, which is why our daytime skies are blue.

Pun said this is considered bad for two reasons. First, it spreads in all directions, so people and animals outside the direct light cannot escape and are still negatively affected.

Second, evidence suggests that blue light is more harmful to animals, including humans, than other colours on the spectrum. A University of Harvard study found blue light threw off participants’ circadian rhythm, raising their blood sugar levels.

LED lights do not, however, need to be demonised. The experts said the carbon-saving benefits of LED lights certainly outweigh the drawbacks, and with thoughtful implementation, LED lights can be installed in a way that reduces light pollution.

Two US-based non-profits focused on lighting, the International Dark-Sky Association (IDA) and the Illuminating Engineering Society, promote five lighting principles to help combat light pollution.

Ashley Wilson, the director of conservation at IDA, said companies and individuals need to consider the following:

-

The usefulness of the light and whether it would be necessary.

-

Could the light be better targeted to avoid spread?

-

Use low light levels, and be mindful of reflections.

-

Can controls be installed such as timers, dimmers or motion sensors?

-

Limit the colour, specifically blue, that the light emits.

With this kind of forethought, along with government or private business incentives, light pollution does not need to become a form of uncontrollable human impact on the environment.

We just need to be smarter about how much light we use and where we direct it

Pun said: “It’s not that hard to fix. The technology is already there; it has been adopted in some places but not everywhere. The reason [it is not widely adopted] is there are some extra costs incurred, but compared to measures you’d have to do afterwards, the costs are very manageable.”

In America, the city of Asheville in North Carolina passed an ordinance in 2018 requiring restaurants to turn off their outdoor lights. A beach town north of Miami, Florida, said in 2019 that beachfront businesses that do not dim their lights at night could be fined US$1,000.

In Hong Kong, one of the world’s worst light polluters, the Environmental Protection Department launched a Charter on External Lighting that encourages businesses to restrict light usage between the hours of 11pm and 7am. Participating companies are rewarded with public recognition from the government for their efforts.

Germany took steps in 2020 to reduce its own light pollution over concerns that it was affecting the insect population.

Study authors McKee and Smyth suggest being wiser about how we light our night and being cognisant of overlighting.

“We just need to be smarter about how much light we use and where we direct it,” said McKee.