Was it an innie or an outie? Scientists find first known evidence of a dinosaur ‘belly button’

- The team found it by analysing a fossil that is famous for its well-preserved skin

- But ‘belly button’ may be an imprecise term to describe the scar

As dinosaurs once again hit the big screen with the recent release of Jurassic World Dominion, one random question that may come to mind is, “did dinosaurs have belly buttons?”

Psittacosaurus are a strange looking dinosaur species famous for grasslike spikes along the end of their tails.

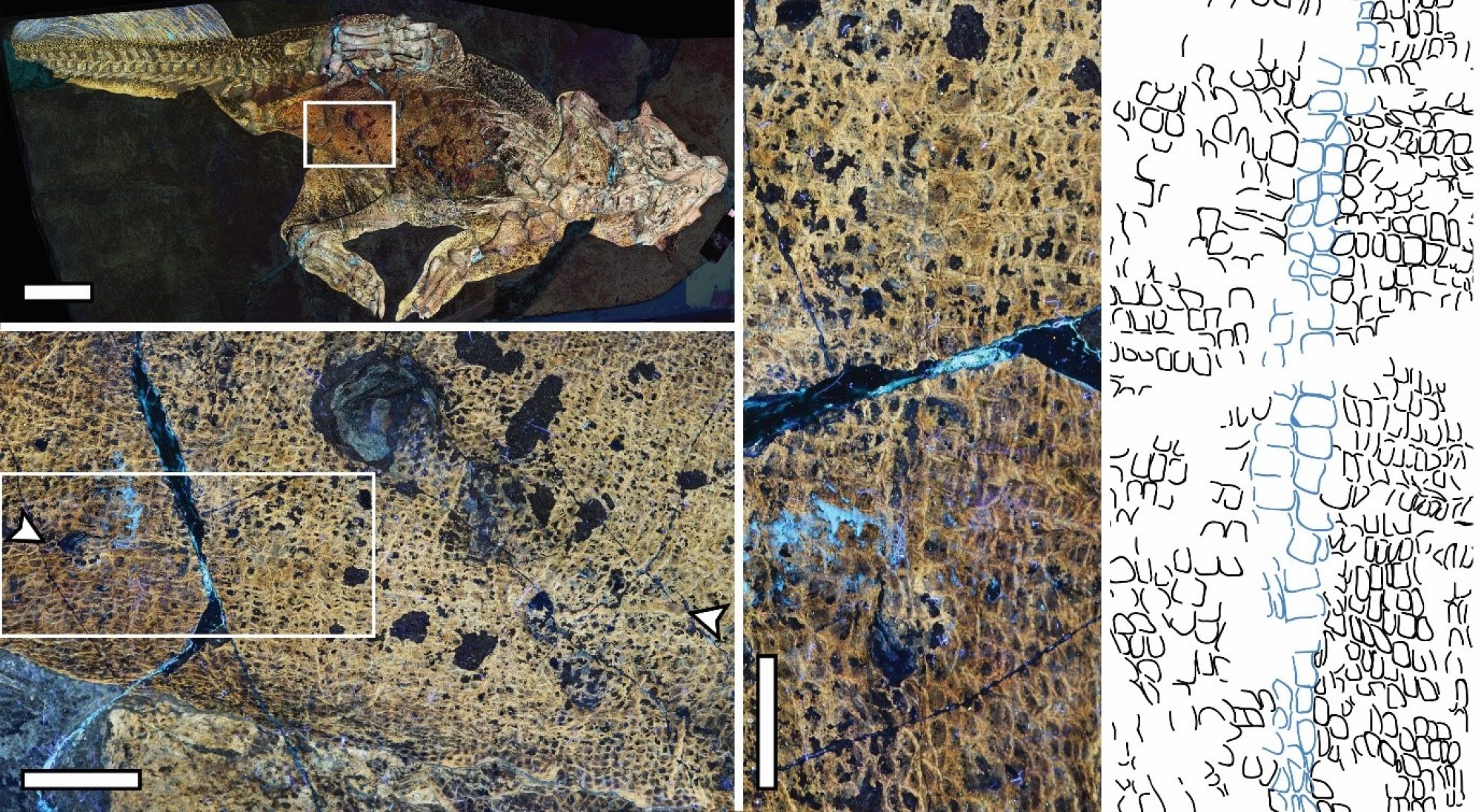

The team found the umbilical scar by analysing laser imaging photographs created in 2016 by Pittman and Thomas G. Kaye, another author of the study.

This particular Psittacosaurus specimen, which was first described in 2002 and was found in Liaoning province in northwest China, also features the best-preserved dinosaur skin of any dinosaur fossil ever discovered.

The team found a large, straight scar on its belly surrounded by a line of scales unique to the rest of the body. This phenomenon is similar to umbilical scars found in modern crocodiles and other reptiles, indicating that the fossil revealed a physiological trend similar to modern reptiles.

“It’s one of those things that, if you are not looking for it, it is kind of hard to find,” said Pittman.

Pittman also pointed out that “belly button” is an imprecise term to describe the umbilical scar because reptiles, birds and dinosaurs develop in eggs, so they do not have true umbilical cords.

Similarly, dinosaur embryos are believed to have been tethered to their eggs so that they could ingest nutrients and oxygen as well as expel waste through sources like egg yolks.

The result is that reptiles and birds do not have belly buttons resembling a human belly button, but the embryo development revealed by umbilical scars is similar to mammals.

One of the more interesting factoids from the discovery was that the Psittacosaurus was relatively old to feature an umbilical scar.

While scars disappear at different times for every animal, the Psittacosaurus was close to sexual maturity, meaning it was around six years old. In modern reptiles, umbilical scars often disappear far earlier.

“We are not saying all dinosaurs had a scar when they were sexually mature, but we are saying that this one had it when it was very old,” said Pittman.

Much like a recent discovery of a duck-billed dinosaur embryo, these findings provide valuable data points for the development of dinosaurs and help us learn how modern animals evolved in the manner they did.

“With technology, we have a chance to nail down the finer details of characteristics we might have expected. And when we do that, we might find things that we did not expect; some nuances,” said Pittman.