Scientists prove a centuries-old theory that a crucial feature in our ability to hear evolved from fish gills

- The team of scientists from China and Europe found concrete evidence of a fossilised ‘spirical gill’

- These spiricals have long been thought to have eventually evolved into the middle ear canal on most land animals

Over 150 years ago, a German anatomist named Carl Gegenbaur theorised that the best place to look for clues into evolutionary history would be by finding similarities in animals that are far different from one another.

According to Per Ahlberg, a professor from Uppsala University in Sweden and a study author, the crucial fact to understand is that all vertebrate embryos have a series of “gill pouches” that will eventually diverge during the animal’s development.

Ahlberg said that in some animals they develop into fully formed gills, but in sharks and rays, it turns into a “miniature gill called a spirical”, which appears like a hole near the eye and is used to intake water to breathe.

The Shuyu fossil exhibited a feature similar to the shark spirical.

In land animals, including humans, the gill pouches develop into our middle ear cavities, which transfer eardrum vibrations into the inner ear and are an essential part of the process for our ability to hear.

“That is how we knew that the middle ear must have evolved from the spiracle,” Ahlberg said.

While many scientists believed in the spirical evolution theory for much of the 20th and 21st centuries, finding definitive proof had been elusive.

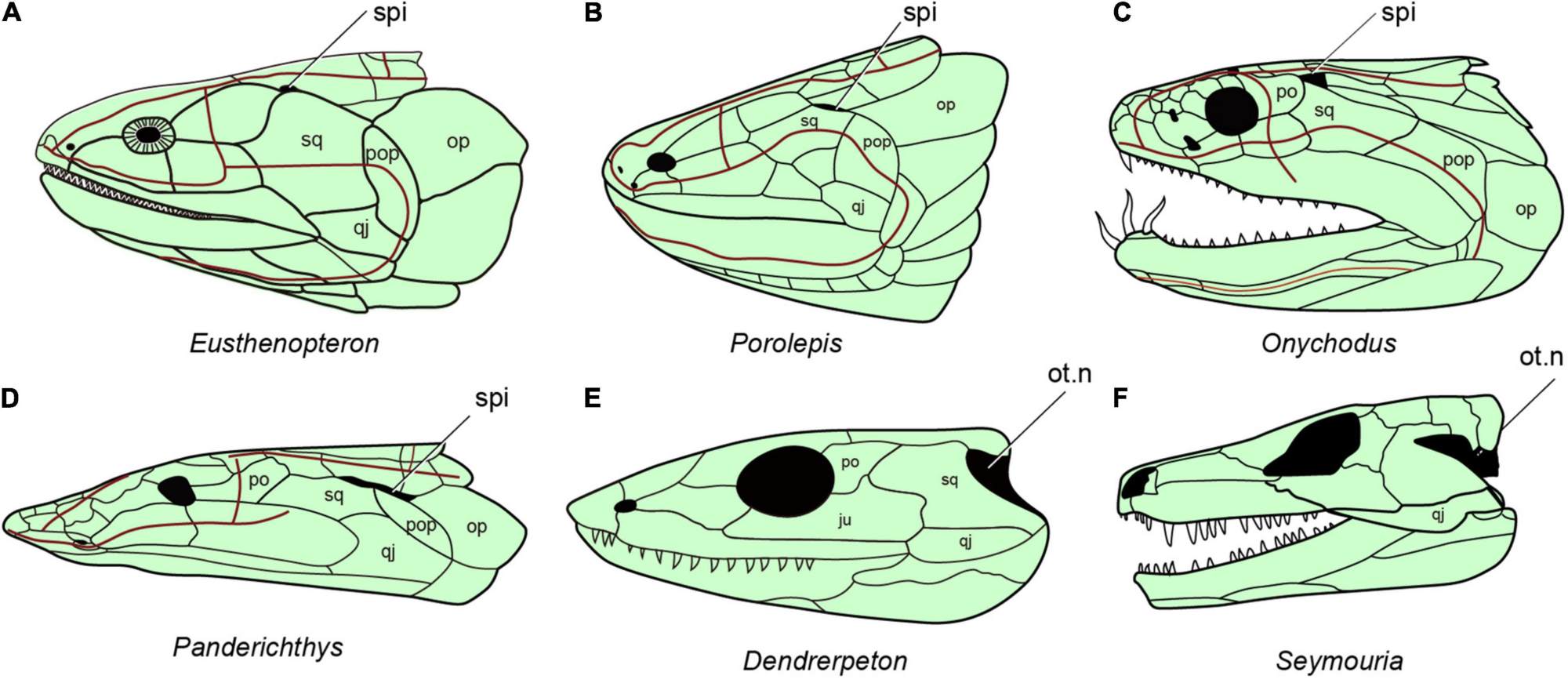

Ahlberg said the new discovery, complete with spirical gills, allows scientists to “bring together recent discoveries” and build a timeline from ancient jawless vertebrates to the middle ears found in the first land animals.

Gai Zhikun, a professor at the Institute of Vertebrate Palaeontology and Palaeoanthropology in Beijing and author of the study, said: “These fossils provided the first anatomical evidence for a vertebrate spirical originating from fish gills.”

Shuyu were jawless vertebrate fish that lived in the Silurian period millions of years ago and looked a bit like a horseshoe crab with thick muscular bodies.

The scientists used a technique called “X-ray tomography microscopy” to analyse the fossils, found in Zhejiang province in eastern China and Yunnan province in southwest China. The new technology allowed them to reconstruct seven fossils and spot the spirical gill pouch, the oldest such example of the feature.

“Many important structures of human beings can be traced back to our fish ancestors, such as our teeth, jaws, middle ears, etc. The main task of palaeontologists is to find the important missing links in the evolutionary chain from fish to humans,” said Zhu Min, a study author from the Chinese Academy of Sciences.