China’s tattoo ban for minors criticised as circular logic and irrational fear of difference, but many welcome new rules

- The ban applies to all citizens under 18, and requires tattoo parlours to advertise the ban and actively discourage minors from seeking body art

- It follows other plans to reinforce ‘masculinity’, a ban on ‘sissy’ men in the entertainment industry and restrictions on gaming and live streaming

China’s move to ban tattoos for people aged under 18 years old has been met with mixed reactions as the government continues to expand state regulation of people’s lives, in particular younger generations.

It is the latest in a growing list of interventions targeting young people that are aimed at restricting and changing behaviour the state views as immoral or what it refers to as “spiritual pollution”.

These moves include plans to reinforce “masculinity” in schools with more male teachers and additional physical education, a ban on “sissy” and “effeminate” men in the entertainment industry and bans on gaming time and live streaming activities for minors.

The tattoo ban for minors under the age of 18 was announced earlier this month by a task force set up to police the behaviour of minors and: “Help them understand the risks of getting tattoos, and parents and guardians should dissuade them from doing so”.

Dr Jonathan Sullivan the Director of China Programs at the University of Nottingham’s Asia Research Institute said the focus on children in recent crackdowns within China was about ensuring future generations conformed to President Xi Jinping’s move to re-embrace “core socialist values” and nurture an “exemplary” society and individuals.

“Everyone in the public eye in China is expected to model exemplary behaviours, because of the influence they are believed to have with regular people, especially children and young people,” he told the South China Morning Post.

“Tattoos, with their long association with negative aspects of society, are not believed to be something that should be modelled for children.”

The move also reflects efforts to clamp down on China’s increasingly privatised cosmetic medical sector as cases of malpractice increase. In one case in June 2021, a tattoo parlour in Jiangsu, eastern China, was sued over the use of toxic colour pigments applied to more than 40 minors.

China’s censors increasingly play the part of morality police

Tattoos are bad because … they are bad?

Within China, many praised the move as necessary to protect young people from being “seduced” into mistakenly getting a tattoo.

Guo Xiamei, an associate professor specialising in family psychology and adolescent development at Xiamen University told the China Daily that young people are not mature enough to make an informed decision when getting a tattoo or understand the “consequences”.

“For example, some careers such as the civil service, policing and the military do not welcome applicants with big tattoos. Adolescents might regret their impulsive or rebellious decision for getting a tattoo when they grow up,” she said.

One online commenter applauding the ban said: “This will ensure younger people do not throw away their future with something that will ruin them in other people’s eyes.”

Hongwei Bao, a professor in Asian identity and media studies at the University of Nottingham in the United Kingdom said the ban reflects China’s older generations’ cultural anxieties about outside influences such as those of the West, against a backdrop of growing employment and social insecurity in Chinese society.

“At a time of heightened political control, unstable economic conditions and intensified global geopolitical tensions, the stakes for being — or simply looking — different are simply too high,” he told the South China Morning Post.

Many on mainland social media were also critical of the move, even as China’s censors worked quickly to remove negative comments.

“How can this improve a young person’s life when there is so much pressure on a good education, getting high-paying jobs and then pressure to marry, have children and own property – this is what they think will help us?,” wrote one commenter.

“Does having a tattoo hurt anyone else? It’s control over our lives for no real benefit. This is a decision made by old, out-of-touch people who come from another time and place,” wrote another.

A long history of judgment

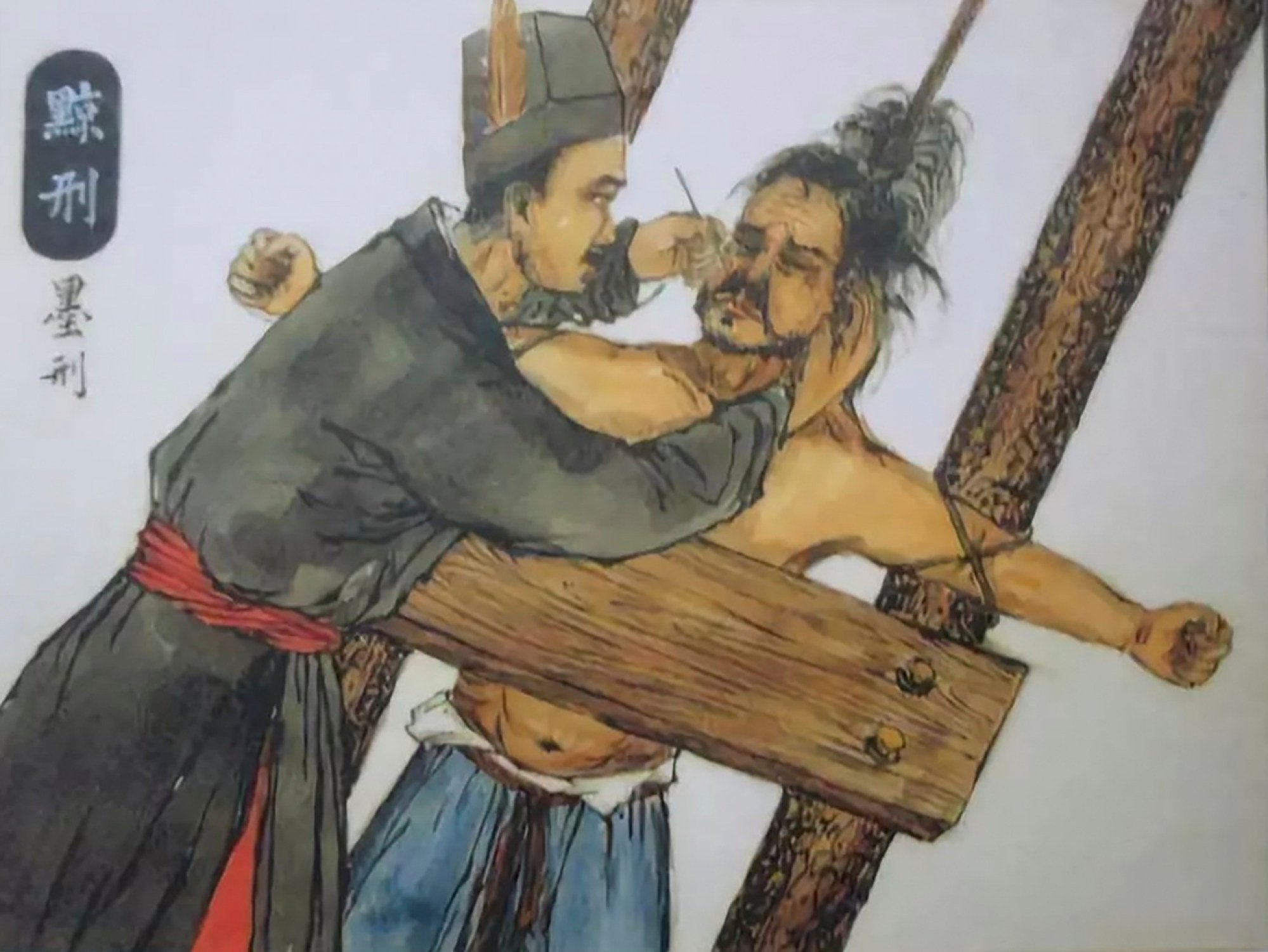

Chinese society’s distaste for tattooing dates back to the time of Confucius and traditional associations between body art and crime and sex work.

“In ancient China, criminals were usually inked as a form of punishment. As people with tattoos were easily recognisable, they usually formed gangs and became social misfits and rebels, and therefore are often associated with gang culture,” said Bao.

“With the changing times, the younger generation have been increasingly aware of international practices and have demanded the right to make decisions about their own bodies, but they are not decision-makers in today’s China,” said Bao.

By 2019 a backlash was building, which coincided with China reaching into the private lives of citizens in an effort to regulate behaviour.

These efforts are designed to remove what some in the government refer to as “spiritual pollution” which can mean anything deemed unworthy by older conservative members of the government but are often Western ideas and trends that have seeped into China in recent decades.

In 2018, elite athletes such as football players, among whom body art is a popular form of self-expression, were ordered to cover up tattoos by China’s General Administration of Sport (GAS).

In January 2019, musicians and actors with tattoos were banned from all mainland Chinese media platforms and shortly after Sina Weibo started removing content that featured tattoos.

Bao said there was a circular logic being applied that was based on other people’s perceptions rather than personal values.

“In a highly competitive Chinese society, there is too much to lose for not fitting into the mainstream. This explains why this policy is also endorsed by many young people. In other words, the tattoo ban can be seen as a majority decision.”