Advertisement

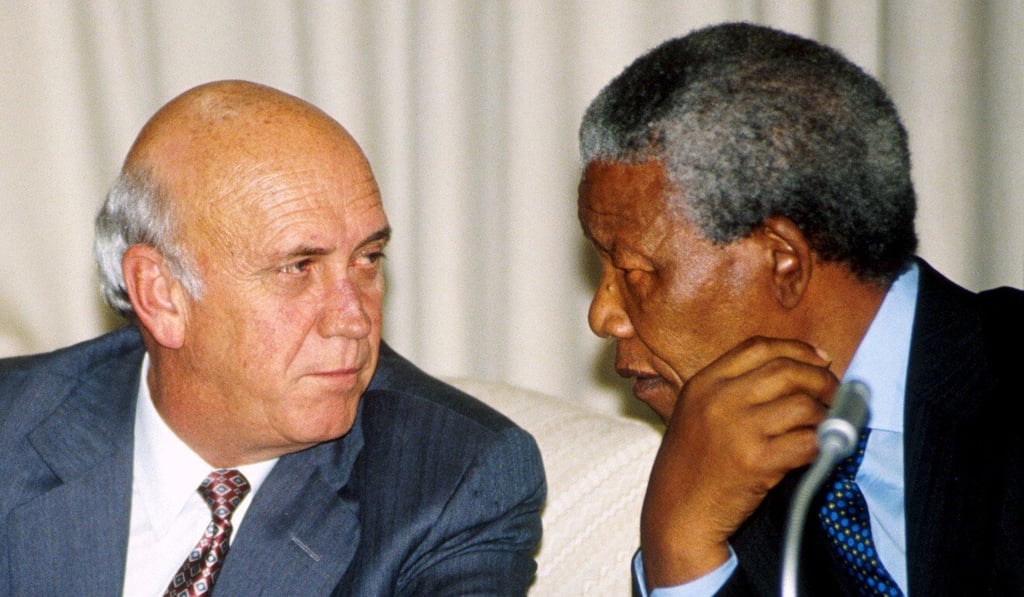

FW de Klerk, last president of apartheid South Africa and key actor in country’s transition to democracy, dies at 85

- In 1990 he announced Nelson Mandela would be released from prison after 27 years; the pair received Nobel Peace Prize in 1993

- In a video released hours after his death, de Klerk apologised for the crimes committed against people of colour in his country

Reading Time:4 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

FW de Klerk, who shared the Nobel Peace Prize with Nelson Mandela, and as South Africa’s last apartheid president oversaw the end of the country’s white minority rule, has died at the age of 85.

He passed away at his home in Cape Town after a battle against cancer, a spokesman for the FW de Klerk Foundation confirmed on Thursday.

In a video released by his foundation on its website hours after his death, de Klerk apologised for the crimes committed against people of colour.

Advertisement

In his message de Klerk also cautioned that the country was facing many serious challenges, saying: “I’m deeply concerned about the undermining of many aspects of the constitution, which we perceive almost day to day.”

Advertisement

“I, without qualification, apologise for the pain and the hurt and the indignity and the damage that apartheid has done to Black, Brown and Indians in South Africa,” de Klerk said.

It was not immediately clear when the recording was made.

Advertisement

Select Voice

Choose your listening speed

Get through articles 2x faster

1.25x

250 WPM

Slow

Average

Fast

1.25x