Malaria mosquito from Asia spreading in Africa, researchers warn

- Scientists alarmed as invasive mosquito species seen as likely responsible for a large malaria outbreak in Ethiopia

- The mosquito species, a main malaria spreader in Indian and Iranian cities, has also been found in Nigeria and Somalia

New evidence has emerged that an invasive species of malaria-carrying mosquito from Asia is spreading in Africa, where it could pose a “unique” threat to tens of millions of city dwellers, researchers warned.

In Africa, home to more than 95 per cent of the world’s 627,000 malaria deaths in 2020, the parasite is mostly spread in rural areas preferred by the dominant Anopheles gambiae group of mosquitoes.

However the Anopheles stephensi mosquito, which has long been a main malaria spreader in Indian and Iranian cities, can breed in urban water supplies, meaning it can thrive during the dry season. It is also to resistant to commonly used insecticides.

Modelling research in 2020 found that if Anopheles stephensi spread widely in Africa it would put more than 126 million people in 44 cities at risk of malaria.

Djibouti became the first African nation to detect Anopheles stephensi in 2012. It had been close to eradicating malaria with just 27 reported cases that year.

However the number has skyrocketed since Anopheles stephensi’s arrival, hitting 73,000 cases in 2020, according to the World Health Organization.

How malaria got its name, and why it was a misnomer

On Tuesday, researchers revealed the first evidence that a malaria outbreak in neighbouring Ethiopia earlier this year was caused by Anopheles stephensi.

In the eastern Ethiopian city of Dire Dawa, a transport hub between the capital Addis Ababa and Djibouti, 205 malaria cases were reported in all of 2019.

However this year more than 2,400 cases were reported between January and May. The outbreak was unprecedented because it took place during the country’s dry season, when malaria has usually been rare.

As the numbers were rising, Fitsum Girma Tadesse, a molecular biologist at Ethiopia’s Armauer Hansen Research Institute, and other researchers “jumped in to investigate,” he said.

They quickly determined that “Anopheles stephensi mosquitoes are responsible for the increase in cases,” Tadesse said.

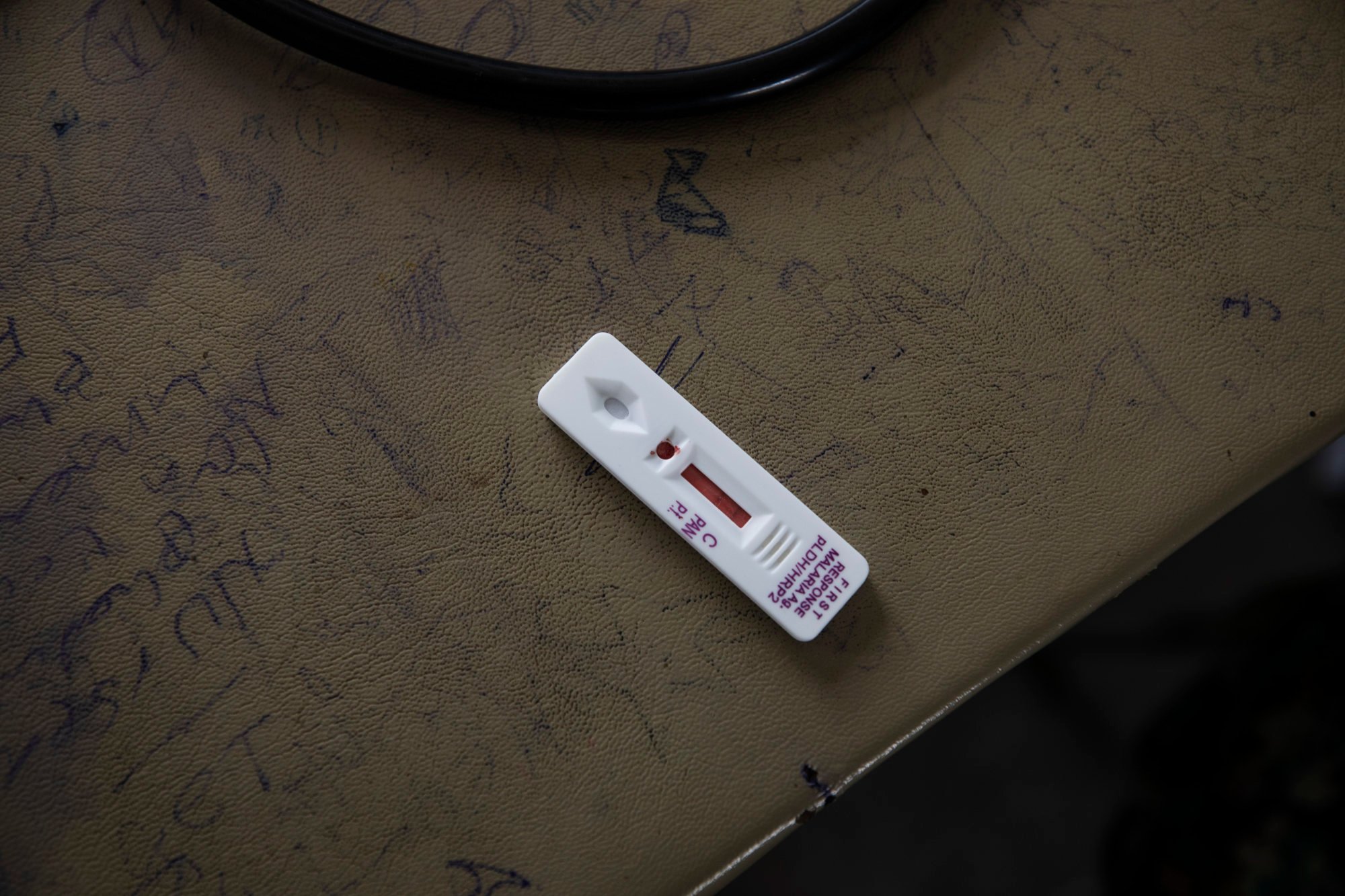

They linked Anopheles stephensi to the infections of the patients, and also found the mosquitoes – carrying malaria – in nearby water containers.

Tadesse warned that the mosquito’s preference for open water tanks, common across many African cities, “makes it unique”.

The research, which has not been peer reviewed, was presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene being held this week in Seattle, US.

Also presented at the conference were early findings that identified Anopheles stephensi at 64 per cent of 60 test sites in nine states of neighbouring Sudan.

The findings come after the Nigerian Institute of Medical Research confirmed in July it had detected Anopheles stephensi in West Africa for the first time.

Malaria made a comeback amid pandemic disruption, WHO says

Sarah Zohdy, an Anopheles stephensi specialist at the US Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, said it was “surprising” that the mosquito was detected so far west, as the focus had been on the Horn of Africa.

In the last couple of months it has been shown that Anopheles stephensi “is no longer a potential threat” in Africa, Zohdy said.

“In the Ethiopian context, this is a threat – we now have data to show that,” said Zohdy, who also works with the US President’s Malaria Initiative, a partner of the Dire Dawa study.

“The evidence now exists to suggest that this is something that the world needs to act on,” she added.

Anopheles stephensi has also been reportedly detected in Somalia, according to the WHO, which in September launched an initiative aimed at stopping the spread of the mosquito in Africa.

Deaths from malaria had more than halved from the start of the century to 2017 – largely due to insecticide-treated mosquito nets, testing and drugs – before progress stalled during the Covid-19 pandemic.

.png?itok=arIb17P0)