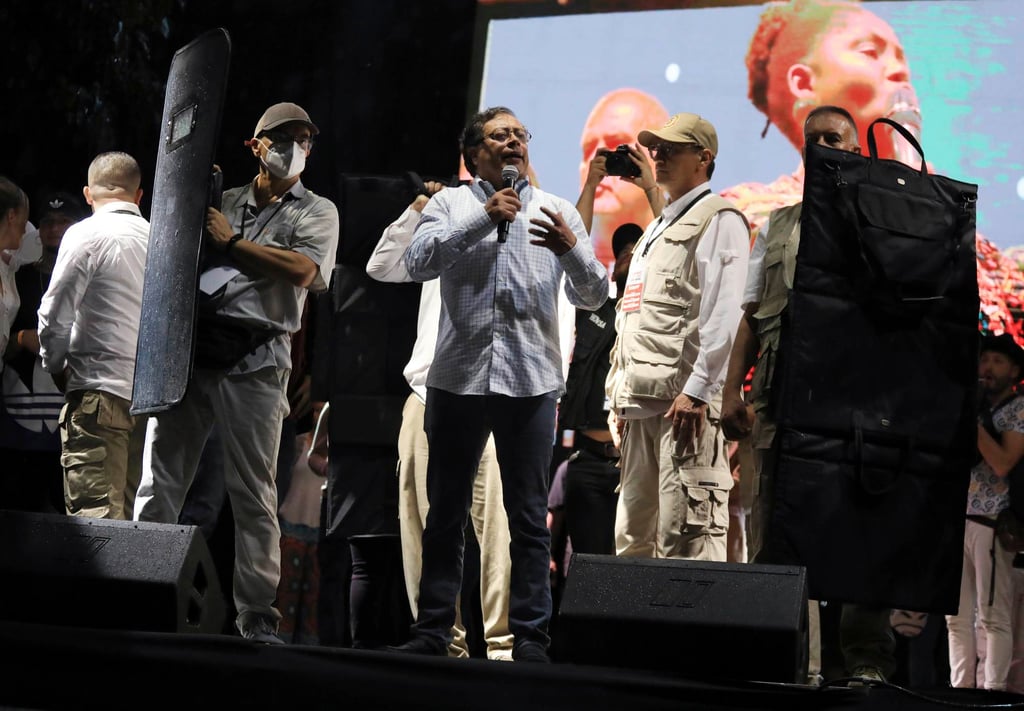

Gustavo Petro, the ex-rebel front runner in Colombian vote, could shake US ties

- If anti-establishment candidate becomes president, he will be the country’s first ever leftist head of state

- Petro aims to renegotiate US free-trade agreement to focus on local producers; he’s also criticised US drug policy and wants to help farmers find alternatives to growing coca, plant used to make cocaine

Fabian Espinel last year helped organise concerts in the streets of Bogotá, as young people protested against police violence and government plans to increase taxes on lower income Colombians.

Now, as his country heads into its presidential election on Sunday, he walks the streets of the capital’s working-class sectors handing out fliers and painting murals in support of Gustavo Petro, the front-runner candidate who could become Colombia’s first leftist head of state.

“Young people in this country are stuck. We hope Petro can change that.” said Espinel, who lost his job as an event planner during the pandemic and received no compensation from his company.

“We need an economic model that is different than the one that has been failing us for years.”

Colombians will pick from six candidates in a ballot being held amid a generalised feeling the country is heading in the wrong direction. The latest opinion polls suggest Petro, a former rebel, could get 40 per cent of the votes, with a 15-point lead over his closest rival. But the Senator needs 50 per cent to avoid a run-off election in June against the second-place finisher.

Should Petro win outright on Sunday or the possible run-off contest next month, the leftist anti-establishment candidate would usher in a new era of presidential politics in Colombia. The country has always been governed by conservatives or moderates while the left was sidelined due to its perceived association with the nation’s armed conflict.