Cuba crisis pitted Kennedy against Khrushchev, Castro

The Cuban missile crisis unfolded like a life-and-death poker game pitting a young American president, John F Kennedy, against the veteran Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev and Cuba’s fiery revolutionary leader, Fidel Castro.

The 45-year-old Kennedy, born to privilege and power, had been in office less than two years when he was faced with the worst crisis of the cold war.

His handling of the failed invasion of Cuba in April 1961 – in which he refused additional American military support for anti-Castro forces – convinced his Soviet counterpart that the US president was weak and indecisive, a view reinforced at a summit between the two leaders in Vienna.

Under intense stress, Kennedy was on numerous medications at the time, including steroids for his colitis, procaine for his back pain, testosterone to increase his weight and antibiotics to prevent the return of an old venereal infection.

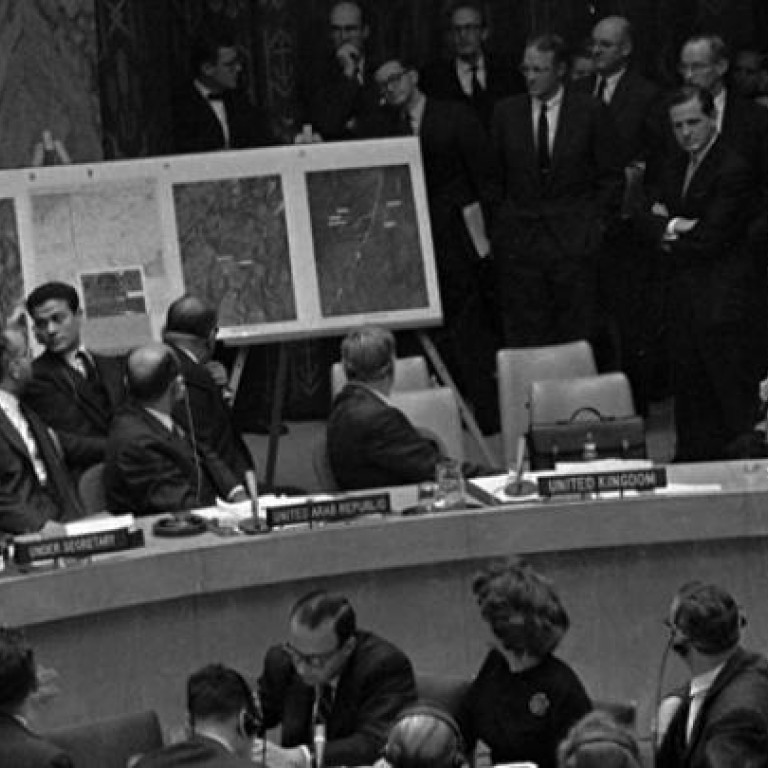

When the missile crisis erupted, Kennedy had to navigate conflicting advice from his divided cabinet, with hawks pushing for an invasion of Cuba and more cautious aides advocating negotiation.

His generals recommended a massive bombing campaign and Air Force chief General Curtis LeMay told the president the decision to impose a naval blockade was akin to appeasing Hitler.

But Kennedy had grown sceptical of the military’s advice after the Bay of Pigs fiasco, and despite pressure from lawmakers and a series of alarming incidents, he finally reached a compromise with Moscow.

Khrushchev’s contempt turned to respect for his American rival. He later wrote in his memoirs that Kennedy had not “overestimated America’s might” and had “left himself a way out of the crisis.”

Kennedy’s hagiographers would later mythologise his role, describing him as facing down the Soviets “eyeball to eyeball”.

But the accounts glossed over the often confused atmosphere inside the US government and how plots Kennedy had authorised to sabotage and overthrow Castro’s regime helped pave the way for Moscow’s actions.

A relieved Kennedy displayed his characteristic black humour after the crisis. Referring to President Abraham Lincoln, who went to the theatre to celebrate the triumphant end to the civil war only to be assassinated, he told his brother: “This is the night I should go to the theatre.”

Kennedy was murdered a little more than a year later, by an assassin who had belonged to a protest group called “Fair Play to Cuba”.

An uneducated peasant who clawed his way to the top of the Soviet leadership, Khrushchev was given to bold strokes and erratic moods.

His decision to station nuclear missiles in Cuba came out of anger over US warheads near his country’s borders and an urge to punch back at the Americans.

But he made the gamble without a plan if the United States discovered the weapons before they were armed and operational.

As a result, he faced a stark choice – pulling back the missiles or fighting a nuclear war.

The bald, rotund Khrushchev was known for his shoe-pounding antics and his threat to “bury” the capitalist system, but he was a far more multi-faceted character than his cartoonish image in the West.

The gentler side of the man known at home as Nikita Sergeyevich revealed a peasant who risked his life to denounce Stalin and who softened the edges of the Soviet system, opening the door to some Western-style products and freedoms.

His 11-year rule over the Warsaw Pact camp is remembered for his 1956 Party Congress speech condemning the cult around Stalin and a period known across Russia as “the thaw”.

Hitherto unseen books were published and jazz records filled store shelves. But – far more importantly to Russians – so did toilet paper and sausages.

The one-time miner was ousted in a well-coordinated conservative pushback in 1964, replaced by the no-nonsense Leonid Breshnev, and he lived out his days in obscurity at a Moscow dacha.

His handling of the Cuban missile crisis was cited by party leaders as one of the reasons for his removal from power. He died from heart failure at the age of 77 in 1971.

Castro came to power only three years before the missile crisis erupted, stunning the world by sweeping aside dictator Fulgencio Batista.

Khrushchev and the elderly men running the Soviet Union were enamoured of the bearded revolutionary, who had defied the mighty United States and repulsed a botched invasion by Cuban emigres bankrolled by the CIA in April 1961.

Born on August 13, 1926 to a prosperous Spanish immigrant landowner, Castro became a communist icon, an unrepentant anti-American leader who managed to hold on to power even after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991.

He led a revolt in 1953 against the Batista regime but his attack on the Moncada barracks in Santiago de Cuba failed, landing him and his brother Raul in prison.

After two years, he was exiled to Mexico, where he built up a guerrilla force and rallied popular support in Cuba against Batista’s corrupt rule.

One he toppled Batista, his sweeping Marxist land and economic reforms failed miserably. He turned to the Soviet Union for help and by buying up Cuba’s sugar and other subsidies Moscow helped keep Castro’s regime afloat despite a strict US embargo that is still in place to this day.

A survivor of numerous CIA plots and assassination attempts, the long-winded Castro tightly orchestrated public life from January 1959 until he suffered a health crisis in 2006 and delegated his duties to his brother Raul Castro.

“El Comandante”, who now lives mostly out of public view due to his bad health, has never expressed regret for his hardline stance during the missile crisis.

In a letter to Khrushchev, he advised Moscow to launch a nuclear attack on the United States before what he believed was an imminent invasion of Cuba.

When he learned of the compromise deal between Khrushchev and Kennedy that required Moscow to withdraw its nuclear missiles from the island, Castro was enraged.

Feeling betrayed and humiliated by his Soviet comrades, who did not consult him about the agreement beforehand, Castro unleashed a torrent of curses on hearing the news, kicking a wall and breaking a mirror, according to historical accounts.

Castro celebrated his 86th birthday in August, with official newspapers publishing congratulatory messages and youth concerts organised in his honour.