Richmond, Canada, residents challenge Chinese-only signage

Residents of North America's most Chinese city grapple with change

Kerry Starchuk has lived in Richmond, British Columbia, her entire life, but lately she feels like a stranger in parts of her hometown.

"Three years ago I started to see the signs," said Starchuk, 55. "I went to Dairy Queen and outside there was a parking sign that had absolutely no English on it. I had no idea what it was trying to tell me."

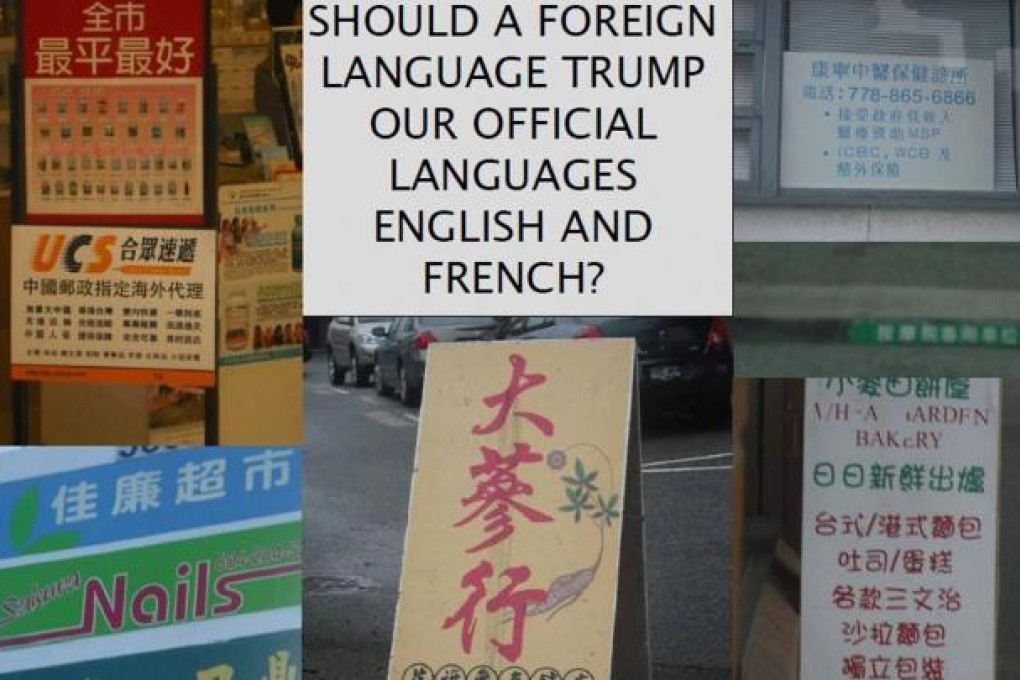

She concluded that English-language street signage was becoming increasingly marginalised in Richmond. Many businesses in the city's most populous districts now favour Chinese signage, sometimes at the total exclusion of English.

Starchuk and fellow Richmond residents failed this week in a bid to get the city council to back a policy requiring business owners to post a certain amount of signage in English or French, Canada's official languages.

She presented a 1,000-signature petition on Monday, but councillors in the Vancouver satellite city of 190,000 voted against even investigating the issue.

"I would have liked for them to agree that this was an issue to be discussed. But they just closed it down," she said on Tuesday. "But it's got people talking and that is probably more important than the petition."