Gene mapping used by US scientists to combat food poisoning

US disease detectives to decode DNA of potentially deadly bacteria

Chances are you've heard of mapping genes to diagnose rare diseases, predict your risk of cancer and tell your ancestry. But to uncover food poisonings?

US disease detectives are beginning a programme to try to outsmart outbreaks by routinely decoding the DNA of potentially deadly bacteria and viruses.

The initial target is listeria, the third-leading cause of death from food poisoning and bacteria that is especially dangerous to pregnant women. Already, the government credits the technology with helping to solve a listeria outbreak that killed one person in California and sickened seven others in Maryland.

"This really is a new way to find and fight infections," said Dr Tom Frieden of the US Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). "One way to think of it is: is it identifying a suspect by a line-up or by a fingerprint?"

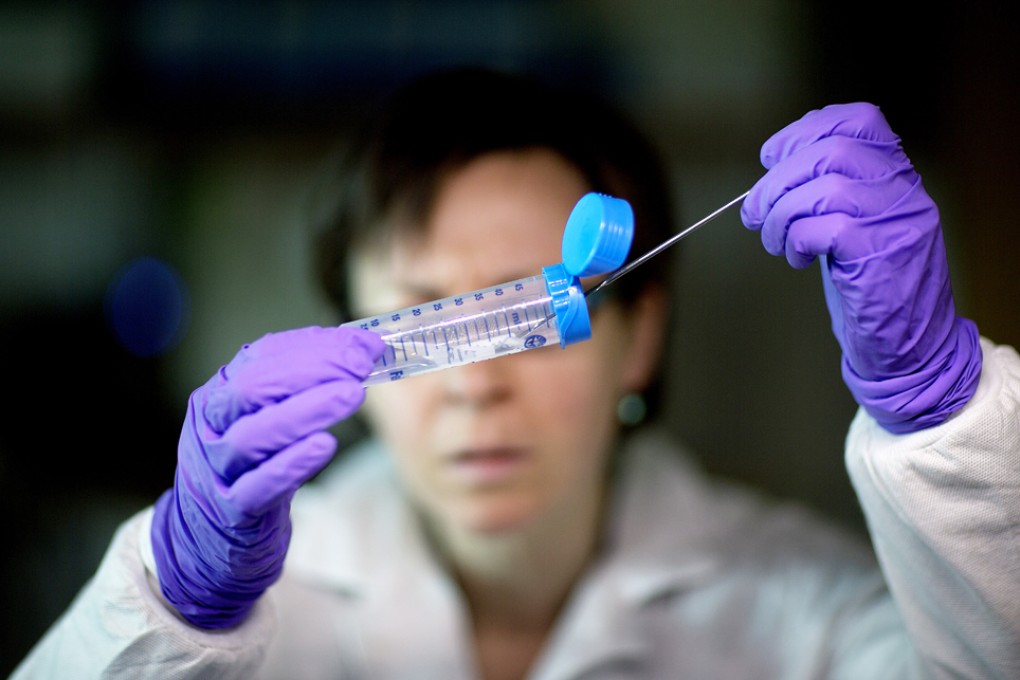

Whole genome sequencing, or mapping all of an organism's DNA, has become a staple of medical research. In public health, it has been used more selectively, to investigate particularly vexing outbreaks or emerging pathogens, such as a worrisome new strain of bird flu.

For day-to-day outbreak detection, officials rely instead on decades-old tests that use pieces of DNA and are not as precise. Now, with genome sequencing becoming faster and cheaper, the CDC is armed with US$30 million from Congress to broaden its use with a programme called advanced molecular detection. The hope is to solve outbreaks faster, foodborne and other types, and maybe prevent infections, too, by better understanding how they spread.

"Frankly, in public health, we have some catching up to do," said the CDC's Dr Christopher Braden, who is helping to lead the work.