Caught in the ‘Playpen’: How computer malware is being used to snare child porn users

The user’s online handle was Pewter, and while logged onto a website called “Playpen”, he allegedly downloaded images of young girls being sexually molested.

Pewter had carefully covered his tracks. To reach the site, he first had to install free software called Tor, the world’s most widely-used tool for giving users anonymity online.

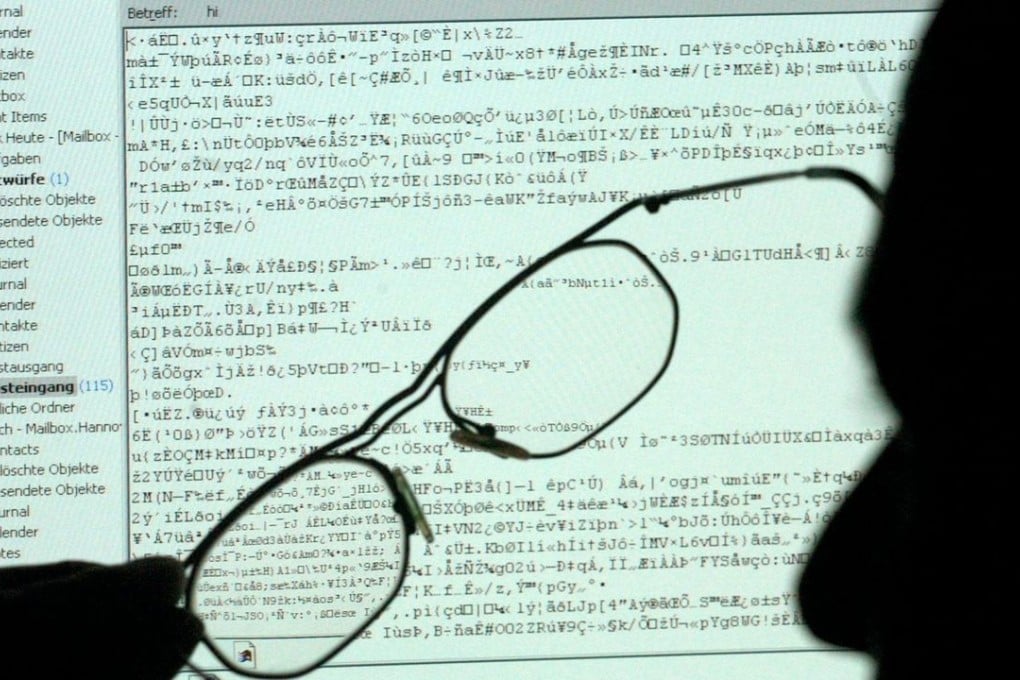

In order to uncover Pewter’s true identity and location, the FBI quietly turned to a technique more typically used by hackers. The agency, with a warrant, surreptitiously placed computer code, or malware, on all computers that logged into the Playpen site. When Pewter connected, the malware exploited a flaw in his browser, forcing his computer to reveal its true Internet protocol address. From there, a subpoena to Comcast yielded his real name and address.

Pewter was unmasked last year as Jay Michaud, a 62-year-old administrator in the Vancouver, Washington, public schools. With a second warrant, agents searched the suspect’s home and found a thumb drive that allegedly contained multiple images of children engaged in sex acts. Last July, Michaud was arrested and charged with possession of child pornography.

Michaud’s is the lead case in a sweeping national investigation into child porn on the so-called dark Web, the universe of sites that are off Google’s radar and where users can operate with anonymity.

As criminals become savvier about using technology such as Tor to hide their tracks, investigators are turning to hacking tools to thwart them. In some cases, US law enforcement is placing malware on sites that might have thousands of users. Some privacy advocates and analysts worry that in doing so, investigators may also wind up hacking and identifying the computers of law-abiding people who are seeking to remain anonymous, people who can also include political dissidents and journalists.