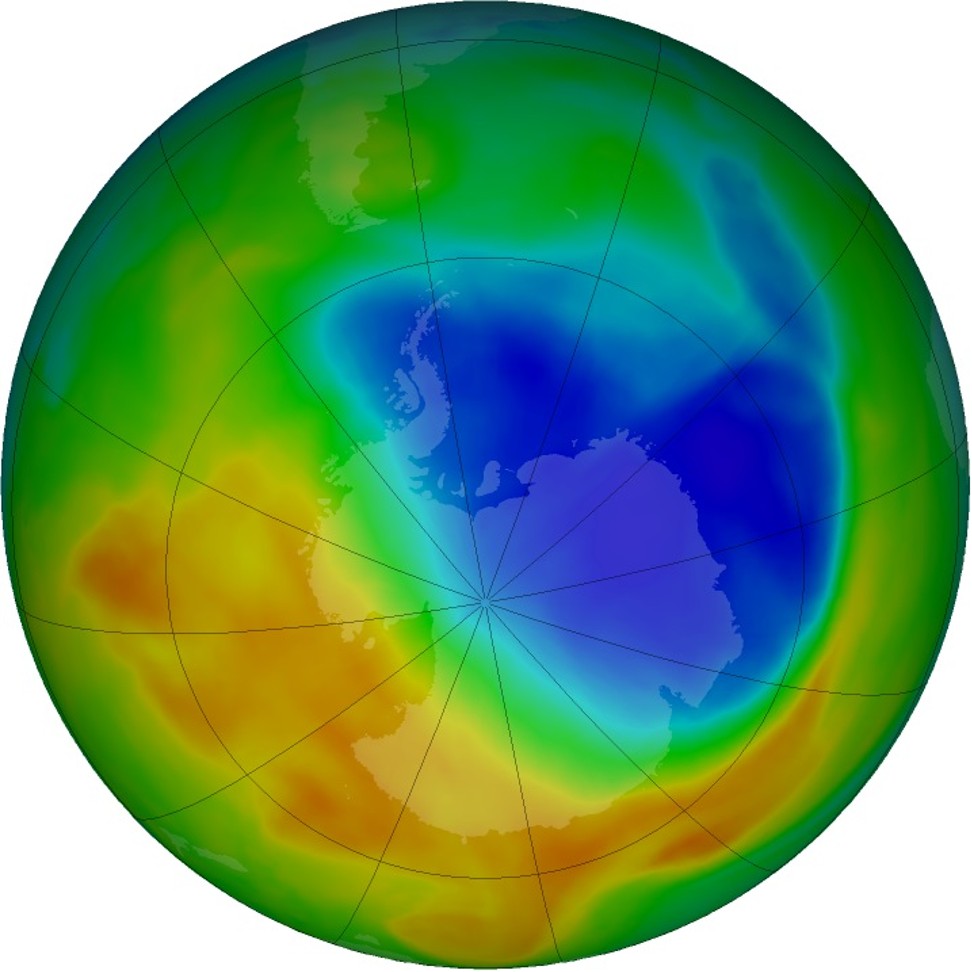

High-flying whodunit: Someone in East Asia is cheating on 1987 Montreal ozone treaty, pumping out huge amounts of banned CFC gas

Production of ozone-eating CFCs have been banned for decades, but somehow 13,000 tonnes are being added to the atmosphere every year from a location in East Asia

Scientists have stumbled on to an atmospheric detective story: someone in East Asia appears to be cheating on a three-decade-old global environmental treaty that banned ozone-eating chemicals.

Researchers from the US, UK and the Netherlands discovered new emissions of a refrigerant that is responsible for about a quarter of chlorine reaching the radiation-blocking ozone layer, according to a paper published Wednesday in Nature.

Chlorofluorocarbon (CFC) levels have declined steadily since being phased out by the 1987 Montreal Protocol – which former United Nations Secretary General Kofi Annan has called “perhaps the single most successful international environmental agreement to date.”

No explanation fits the data better than new production, the scientists report. They detected a spike in the difference between atmospheric levels in the Northern and Southern Hemispheres, suggesting facilities in the highly industrialised north.

They then used air-pollution modelling to backtrack possible origins of the air they sampled, to East Asia. As much as 13,000 tonnes of CFC-11 is joining the atmosphere every year.

[If] 13,000 tonnes escape to the atmosphere, how much is being made? That’s some leak

If “13,000 tonnes escape to the atmosphere, how much is being made? That’s some leak,” said Johannes Laube, a University of East Anglia research fellow who reviewed the paper for the journal.

Stephen Montzka, lead author and an atmospheric chemist with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, said the paper delivers “hard-evidence” of renewed production, despite potential complicating factors, such as the variable movements of high-flying air masses and the residual emission of CFC-11 from materials that were common in building construction.

The study is rare in that it may have both profound ecological and political implications. It’s difficult to say which are more pronounced.

Calculations suggest that a couple of decades of CFC-11 production at the new observed levels might delay the return of the ozone hole to its 1980-scale by only a decade – around the middle of the century.

“The sky isn’t falling,” Montzka said.

But diplomats may not feel the same way.

“Such a careful analysis is crucial, because any claim of renewed – and therefore illegal – emissions will have political implications,” wrote Michaela Hegglin, a University of Reading atmospheric chemist, in a companion Nature essay.

Laube similarly emphasised the possible violation of international regulation.

“This is quite convincing. There’s quite strong evidence that points to illegal emissions of these CFCs,” he said.

Potential cheating comes to light just as the international community is amending the Montreal Protocol to accommodate new threats.

Nations moved very quickly in the mid-1980s to sign the treaty, in part because industry had found replacement refrigeration chemicals that do not destroy stratospheric ozone.

However, these chemicals, the hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), turned out to be virulent greenhouse gases, many hundreds or thousands of times more potent than CO2, even if their low abundance make them a lesser contributor overall to global warming.

Montreal Protocol signatories gathered in Kigali, Rwanda in 2016 to observe the treaty’s 30th anniversary and to sign off on an amendment that would ban HFCs. It will go into force on January 1, 2019.

The Trump administration has not said whether it will support the so-called Kigali Amendment.

Montzka and some of the other authors are members of the Montreal Protocol’s Scientific Assessment Panel, one of three advisories that keep signatory nations up-to-date on relevant issues. Montzka shared the results of their study with the UN before publication.

“Issues of concern, including the findings discussed in the scientific article” will be presented to member nations, said Dan Teng’o, spokesman for the UN’s Ozone Secretariat, which administers the agreement. The panel is compiling its quadrennial report, expected to be released later this year.

The treaty process “assists non-compliant parties to return to compliance through a cooperative, non-confrontational process that focuses on amicable solutions,” he said. “This is one of the factors behind the success of the Protocol.”

Montzka said the team’s next step will be to try and focus in on the source of the emissions, drawing on measurements in East Asian nations, an effort lauded by environmentalists.

“We know the Montreal Protocol is working because, in general, the amounts in the atmosphere correspond with the inventory of emissions,” said David Doniger, senior strategic director of the Natural Resources Defence Council’s Climate and Clean Energy Program. “When the two are out of whack, as here, the detectives go to work to find out why.”