Analysis: with drone attacks, the era of joystick terrorism appears to have arrived

Attacks in Venezuela and Abu Dhabi demonstrate the threats posed by drones to heads of state and air passengers alike

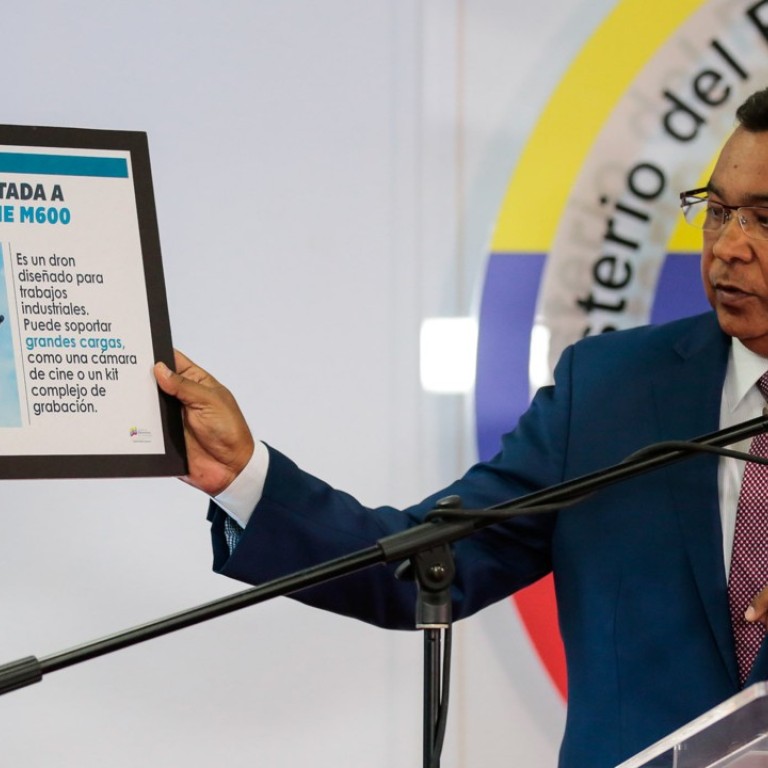

A failed assassination attempt against Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro on Saturday was mounted with explosive-armed drones, according to news reports.

Nine days earlier, and on the other side of the world, a group claimed to have sent an armed drone to attack the international airport in Abu Dhabi.

Venezuela arrests six over drone attack on President Maduro

No one was killed in either case, and the circumstances of both remain murky. But a new and dangerous era in non-state-sponsored terrorism appears to have begun, and it is unclear whether authorities are equipped to counter it.

In Abu Dhabi, Houthi rebels from Yemen said they launched a drone attack at the airport. UAE authorities deny the incident occurred, but it is technically possible for the rebels to have done so.

But these episodes may encourage other technologically savvy groups and disgruntled individuals to use drones to commit political violence.

Militant groups such as Islamic State have already used drones to carry out attacks by dropping grenades or crashing into infrastructure.

Venezuela’s President Maduro escapes ‘drone assassination’ attempt

There have also been incidents that raised the possibility of attacks on heads of state. In January 2015, a drone crashed onto the White House lawn after its operator lost control, prompting concerns that the US president’s home could be vulnerable.

A few months later, a man protesting against Japan’s nuclear policy dropped a drone carrying radioactive sand from the Fukushima nuclear disaster onto the prime minister’s office, though the amount of radiation was minimal.

Earlier this year, Saudi Arabian security forces shot down a recreational drone near a royal palace, briefly prompting speculation of a coup attempt.

Some activist groups have also used drones to spread their message.

In July, Greenpeace crashed a Superman-shaped drone into a French nuclear plant to demonstrate its vulnerability to attacks.

Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs, or drones) represent a fresh threat to the travelling public.

Weaponised drones start with a tactical advantage: most can fly lower than current technology is capable of readily detecting. Even if they were carrying only a small quantity of explosives, they could bring down a civilian aircraft in flight, some experts say.

Commercial airliners are vulnerable during take-off and landing when there is limited time for aircrews to react to unforeseen and potentially hostile events.

A simple hobbyist’s drone can down an aeroplane when joysticked into the airliner’s path.

Militarised drones, the kind probably available to groups such as the Houthis, are heavier and can carry several pounds of explosives at speeds up to 160km/h with a range of 650km.

Airport security, as currently designed, is focused on ways to mitigate threats from people who have access to the facility, such as passengers and staff, and from cargo transiting the grounds. Airports are not designed to guard against attacks from the sky.

Many counter-drone systems, such as “jammers” intended to sever the link between an operator and a vehicle, may be difficult to deploy in non-combat zones because of the risk that they could interfere with crucial communications like commercial aircraft or law enforcement channels, according to Dan Gettinger, co-director of the Centre for the Study of the Drone at Bard College (CSD).

“There are a number of challenges to deploying these measures in the domestic space,” Gettinger said. A report by the centre recently identified more than 200 anti-drone systems on the market, aimed at either detection or interdiction.

The US Department of Defence sought US$1 billion for counter-drone measures in its proposed 2019 budget, according to the CSD.

There are limits to the likely impact of any drone attack launched by non-state actors. In a recent post, Scott Stewart, an analyst with the global security consulting firm Stratfor, wrote that military ordnance or military-calibre drones are extremely difficult to obtain, while homemade explosives are typically far less lethal.

But experts say the psychological effects of a small but successful attack could far outstrip the actual physical damage.

“With a Twitter account and a toy drone, you can really cause a lot of panic these days,” said Colin Clarke, an analyst with policy think tank the RAND Corporation. “That’s a big part of terrorism – the psychological aspect. Even if you can’t kill large numbers of people, you can still cause fear.”

Additional reporting by Reuters