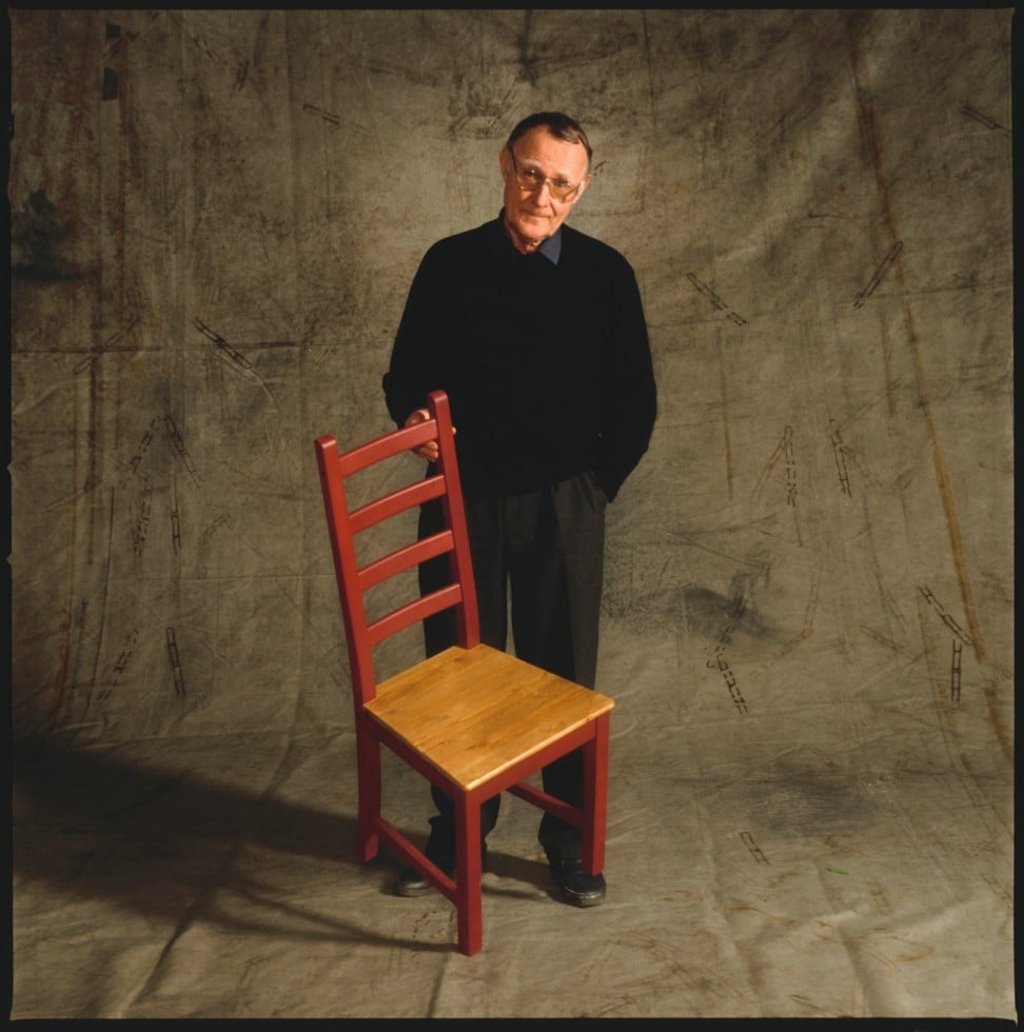

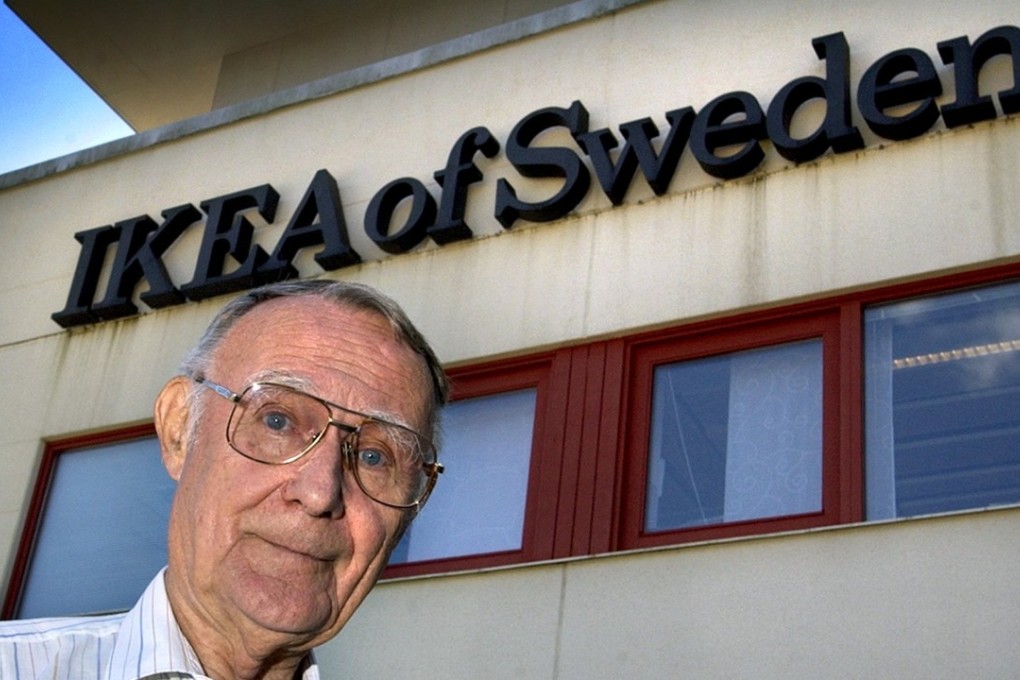

Analysis | How Ikea’s Ingvar Kamprad changed the way we think about furniture (and Swedish meatballs)

Analysts say Ikea has been successful in not only getting shoppers to linger for hours, but also getting them to come back, over and over, whether for mattresses or meatballs

There’s the Billy bookcase, the Malm dresser and, who could forget, the no-nonsense Lack coffee table.

Since its founding in 1943, the company has transformed the way we think about how we shop for furniture (out: catalogues, in: mazelike warehouses), how we put it together (ourselves) and how it looks (sleek, not stodgy.)

With its clean lines and practical pieces, Ikea has outfitted millions of college flats and brought a Scandinavian aesthetic into everyday homes.

“Few people can claim to have genuinely revolutionised retail,” said Neil Saunders, managing director of the research firm GlobalData Retail.

“Ingvar Kamprad did.”