Spain’s PM Pedro Sanchez angrily defends his thesis against plagiarism claims

The prime minister is the latest politician to have his educational history scrutinised

Spain’s prime minister, Pedro Sanchez, has published his doctoral thesis online in an effort to put an end to allegations of plagiarism and distance himself from the degree scandal that has dogged some of the country’s most high-profile politicians.

Sanchez, whose socialist party came to power in June after ousting the corruption-mired conservative government of Mariano Rajoy, has become the most senior political figure to find their educational history under intense scrutiny.

On Tuesday night, the health minister, Carmen Monton, resigned following a series of reports detailing irregularities in her master’s degree, which was awarded by the public King Juan Carlos University (URJC) in Madrid seven years ago.

Pablo Casado, who succeeded Rajoy as leader of the People’s Party (PP), is also facing questions over this postgraduate qualifications.

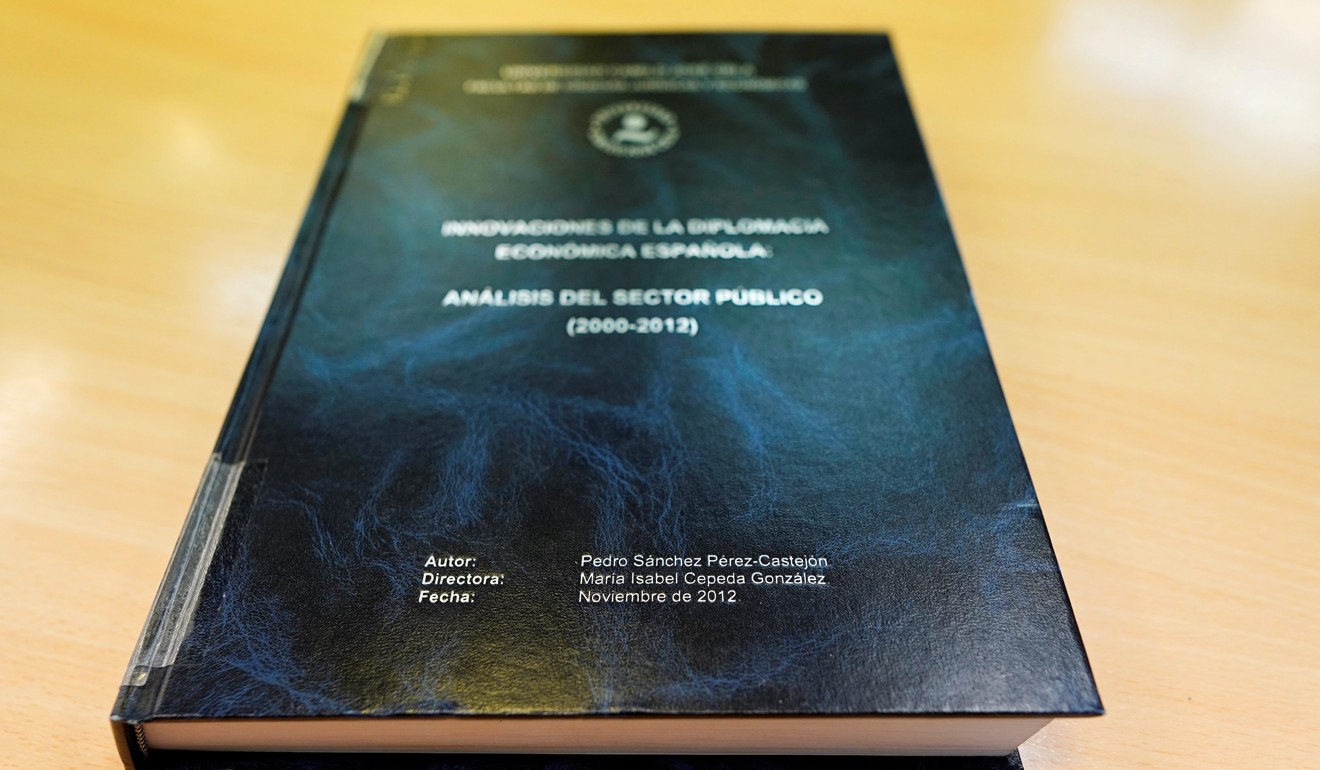

The prime minister’s thesis – submitted in 2012 and entitled Innovations in Spanish economic diplomacy: public sector analysis (2000-2012) – is the latest work to be pored over by opposition parties and the Spanish media.

In several articles this week, the conservative daily ABC accused Sanchez of plagiarising official reports, other authors, and his own co-written works.

Albert Rivera, leader of the centre-right Citizens party, urged the prime minister to make his thesis public, saying there were “reasonable doubts” over the work.

Sanchez reacted angrily to the accusations on Thursday, dismissing them as “completely false” and threatening legal action “to defend my honour and dignity” if the articles were not corrected.

He also announced that his thesis, written while he taught economics at the private Camilo Jose Cela University, would be available online for all to see.

“No matter how much they try to smear me, I am proud of my university thesis,” he wrote on Facebook.

“They will not tarnish something that cost me so much work.”

Before the thesis was posted electronically, the Spanish government issued a statement saying the text had been run through two plagiarism detection programmes – Turnitin and PlagScan – and had “comfortably passed” both.

Sanchez’s PSOE party may have been the focus of the latest round of the so-called “mastergate” scandal, but the issue could yet inflict further damage on the PP.

Earlier this year, it emerged the postgraduate degree Casado claims to hold from Harvard had in fact been earned by attending a four-day course in Madrid.

The conservative leader has also admitted he was awarded a master’s degree in public regional law by the URJC – the same university that awarded Monton her degree – despite not being required to attend classes or take exams.

Spain’s Supreme Court is currently looking into Casado’s master’s degree and is due to determine whether the investigation should continue.

The PP has stressed that the allegations that Casado faces are very different from those that brought down the health minister, pointing out that its leader has not been accused of falsification or plagiarism.

But the PSOE has tried to focus the spotlight on Casado, calling for his resignation and claiming “he’d have been charged by now” if he did not enjoy the judicial privileges of being an MP.

Nor is Casado the only senior PP member whose master’s from the URJC has been questioned.

Cristina Cifuentes, the PP head of Madrid’s regional government, had faced growing pressure to quit over allegations of irregularities in her master’s before she stepped down in April after video footage emerged of her apparently being caught stealing two tubs of face cream seven years ago.

Observers say the “mastergate” affair also speaks volumes about the ubiquity of titulitis – the drive to accumulate qualifications – in Spanish politics.

“There seems to be a need for certain politicians to prove that they have the merits to be in politics,” said Antonio Barroso, an analyst at the political risk advisory firm Teneo Intelligence.

“But you don’t need to be qualified to be a good politician; for example you don’t need to be a political scientist to be a politician.”

Pablo Simon, a political scientist at Carlos III University in Madrid, said the spread of titulitis was down to both economics and politics.

“Universities have been hit by a continuous series of cuts and funding reductions, and many departments depend on master’s courses to bring in additional resources,” he said.

“The income of lots of university teachers depends on the success of these courses and that can end up in blatant cases of cronyism or bringing standards right down.”

In the political sphere, said Simón, people tended to try use qualifications to justify their appointments to certain jobs.

“People get put in their roles because of their proximity to the leader, which makes them seek out additional legitimacy through qualifications.”

However, Barroso said the current series of scandals could serve to bring greater transparency to what had previously been an opaque area.

“We know that some years ago, after the [economic] crisis, some politicians were changing their CVs. It was mentioned but nobody cared. Now, the level of scrutiny by the media is so high that the threshold has gone up. And I think that’s extremely healthy for democracy. Holding politicians accountable isn’t only about their actions, but also about what they claim to be.”