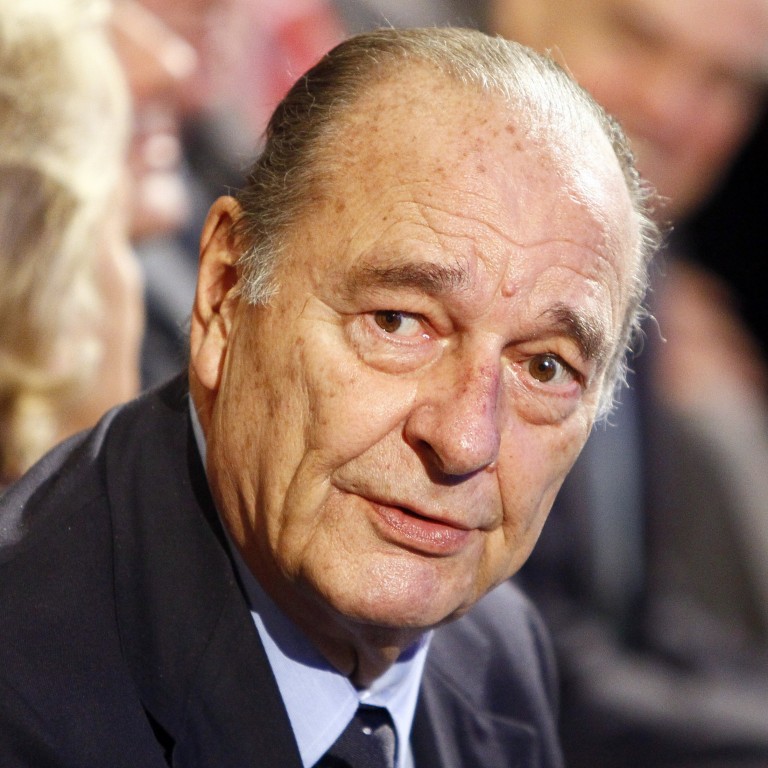

Former French president Jacques Chirac dies, aged 86

- Chirac led France from 1995 to 2007, making him the country’s second-longest serving leader

- He was convicted for misuse of public funds, but also stirred national pride by opposing the US-led invasion of Iraq in 2003

Former French president Jacques Chirac, who led France from 1995 to 2007, died on Thursday morning at the age of 86, his family confirmed.

“He passed away peacefully this morning surrounded by his loved ones,” his son-in-law Frederic Salat-Baroux said.

The head of the lower house of the French parliament interrupted a sitting of the chamber to hold a minute’s silence.

Chirac, France’s second-longest serving president dominated French politics for decades.

After leaving public office, he suffered from neurological problems, and was rarely seen in public at the end of his life.

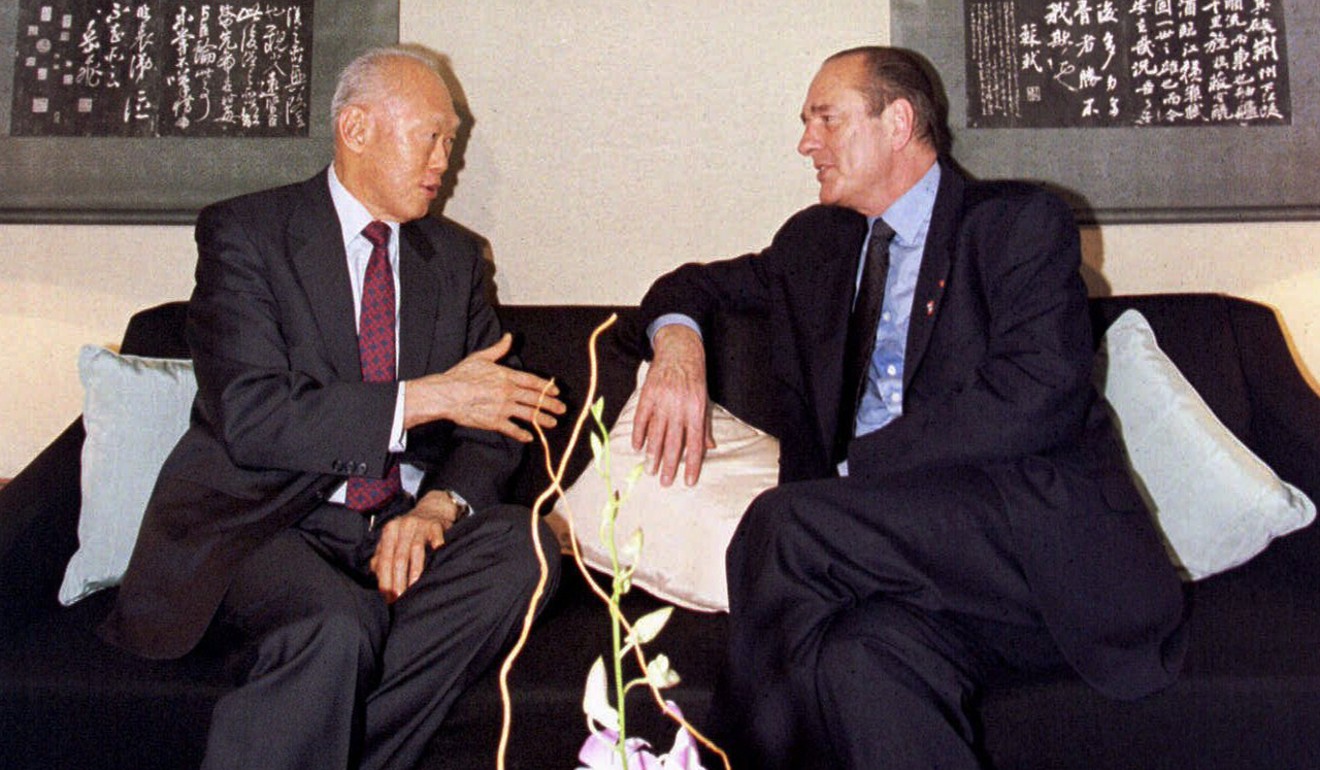

For many, Chirac’s statesmanlike but jocular air encapsulated both France’s rural roots and its central role in diplomatic affairs.

The frenetic energy and brashness of his successor Nicolas Sarkozy left many pining for the quieter days of Chirac’s 12-year presidency and the slower pace he set for public life.

Chirac was often recalled through his persona as a puppet on a popular TV show and for quirks like his taste for the Mexican beer Corona, his poor English and a seeming aloofness.

He was also a puzzle: he enjoyed Asian art and Japanese poetry but liked to play down his intellectual side. A commentator once described him as the kind of man who would read a book of poetry behind a copy of Playboy.

His changing political views earned him nicknames like Chameleon Bonaparte and the Weathervane.

He was also nicknamed Houdini because of his knack for wriggling out of tight spots.

His reputation survived a conviction for misuse of public funds in December 2012, which made him the first head of state convicted since Nazi collaborator Marshal Philippe Petain in 1945.

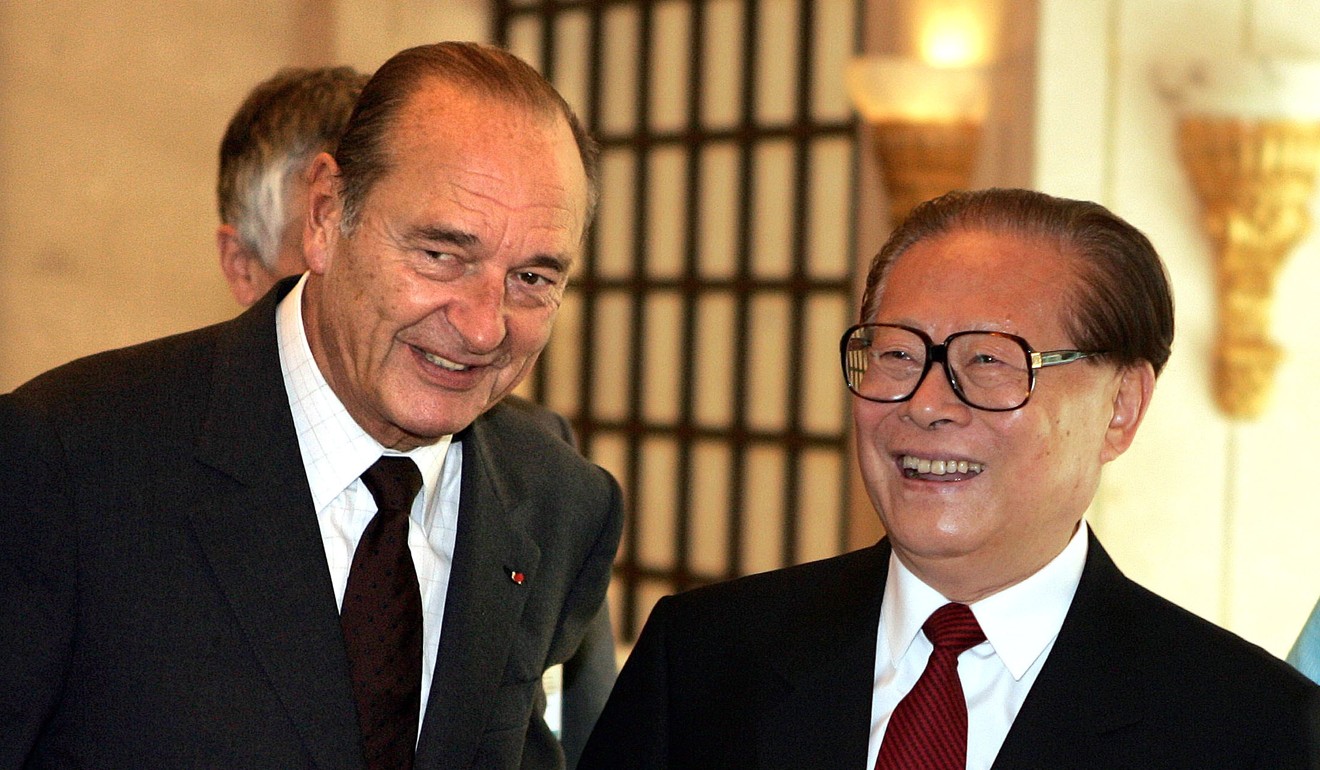

Following in the footsteps of de Gaulle, Chirac devoted much of his presidency to defending France as a great nation on the world stage – a reputation he bolstered when he threatened to use his UN Security Council veto against a resolution that would authorise military force to find and eliminate weapons of mass destruction in Iraq in 2003.

“We are not refusing or rejecting war outright. If we have to wage war … we are not pacifists. We are not anti-American either,” Chirac told CNN on March 17, 2003.

France’s Sarkozy to go on trial after final appeal fails

Three days later, the United States and Britain invaded Iraq without UN approval. No weapons of mass destruction were ever found.

After retiring from public office, Chirac drew crowds of journalists and admirers in one of his last public appearances which was, characteristically, a visit to the 2011 annual Farm Show.

Born in 1932 in Paris to a middle-class family from the central rural region of Correze, Chirac began his political career in the late 1950s after studying at the elite Sciences Po university and ENA civil service academy.

As a teenager, he briefly sold the communist newspaper L’Humanite on Paris street corners. He also developed an enduring love of the United States, crossing the country doing odd jobs – including a spell washing dishes.

Yet his early leanings seemed forgotten when he became an army officer and linked up with the ultranationalist Algerie Francaise party – only to change tack again to become a moderate Gaullist and, by 1967, an ambitious junior minister.

He rose fast but also made enemies quickly. He ripped apart the old Gaullist movement in 1974, backing non-Gaullist moderniser Valéry Giscard d’Estaing for president.

Chirac was just 41 when Giscard made him prime minister on May 28, 1974, after winning power, but he quit two years later after falling out with Giscard over the extent of his powers.

He turned his back on Giscard by forming a new Gaullist party of his own, the Rally for the Republic (RPR) in 1976, which then become the Union for a Popular Majority (UMP), and changed name again to the current Les Republicains.

The following year he was elected as Paris’ first mayor – starting an 18-year career at City Hall that would come back to haunt him.

After nearly two decades of investigations, he was handed a two-year suspended prison sentence in 2011 for channelling public money into phantom jobs for political cronies as mayor from 1977 to 1995. Although eventually convicted, Chirac was excused from attending the trial due to his failing memory.

Supporters would prefer that he be remembered for electoral victories in 1995 and 2002, when was re-elected after a fraught battle with far-right candidate Jean-Marie Le Pen.

He secured a landslide victory in that election but that was more a vote against Le Pen than a resounding vote of confidence.

Though President Georges Pompidou once referred to him as a “bulldozer” for his ability to get things done, Chirac’s presidency is remembered mostly as a time of stasis.

He ended compulsory military service and started moves that reintegrated France into the Nato defence alliance, reversing a policy set in the 1960s.

He sought as president to reduce unemployment and cut public debt, and steered France into Europe’s monetary union, but did little to modernise the economy or the state.

He became one of Europe’s main standard bearers. He forged an alliance with German Chancellor Gerhard Schroeder which brought Europe’s two traditional powers closer together but upset some of their European Union partners.

He is, however, acknowledged as the first French head of state to recognise the role of the Vichy regime in the Holocaust and the first to apologise formally to the Jewish people.

After leaving the Elysee in 2007, he lived a quiet life with his wife Bernadette on Paris’ Quai Voltaire in a flat loaned by Lebanon’s Hariri family, and worked on his memoirs.

His wife frequently appeared at social events, however, and commented in an interview that her husband preferred to stay at home watching television.

During one of his last notable public sorties in mid-2011, Chirac sparked a furore when he said he would vote in the next year’s presidential election for Socialist Francois Hollande rather than a second term for Sarkozy, his dislike for whom was well-known.

Hollande won the contest, but it was never established that Chirac carried out his threat because the ailing former president’s vote was cast by Bernadette.