German scientists help paralysed mice walk again

- Researchers injected the animals’ brains with a designer protein that re-established a neural link previously thought to be irreparable in mammals

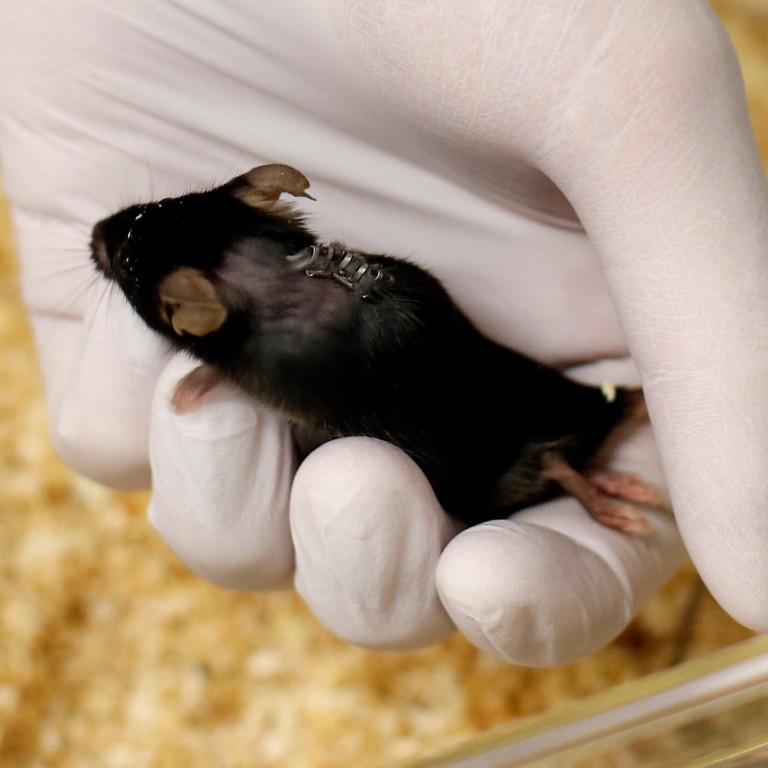

- The rodents, which had spinal cord injuries, were able to walk again two or three weeks after treatment

German researchers have enabled mice paralysed after spinal cord injuries to walk again, re-establishing a neural link hitherto considered irreparable in mammals by using a designer protein injected into the brain.

Spinal cord injuries in humans, often caused by sports or traffic accidents, leave them paralysed because not all of the nerve fibres that carry information between muscles and the brain are able to grow back.

But the researchers from Ruhr University Bochum managed to stimulate the paralysed mice’s nerve cells to regenerate using a designer protein.

“The special thing about our study is that the protein is not only used to stimulate those nerve cells that produce it themselves, but that it is also carried further [through the brain],” the team’s head Dietmar Fischer said in an interview.

“In this way, with a relatively small intervention, we stimulate a very large number of nerves to regenerate, and that is ultimately the reason why the mice can walk again.”

The paralysed rodents that received the treatment started walking after two to three weeks, he said.

The treatment involves injecting carriers of genetic information into the brain to produce the protein, called hyper-interleukin-6, according to the university’s website.

Gene editing breakthrough in mice offers Parkinson’s hope

The team is investigating if the treatment can be improved.

“We also have to see if our method works on larger mammals. We would think of pigs, dogs or primates, for example,” Fischer said.

“Then, if it works there, we would have to make sure that the therapy is safe for humans too. But that will certainly take many, many years.”