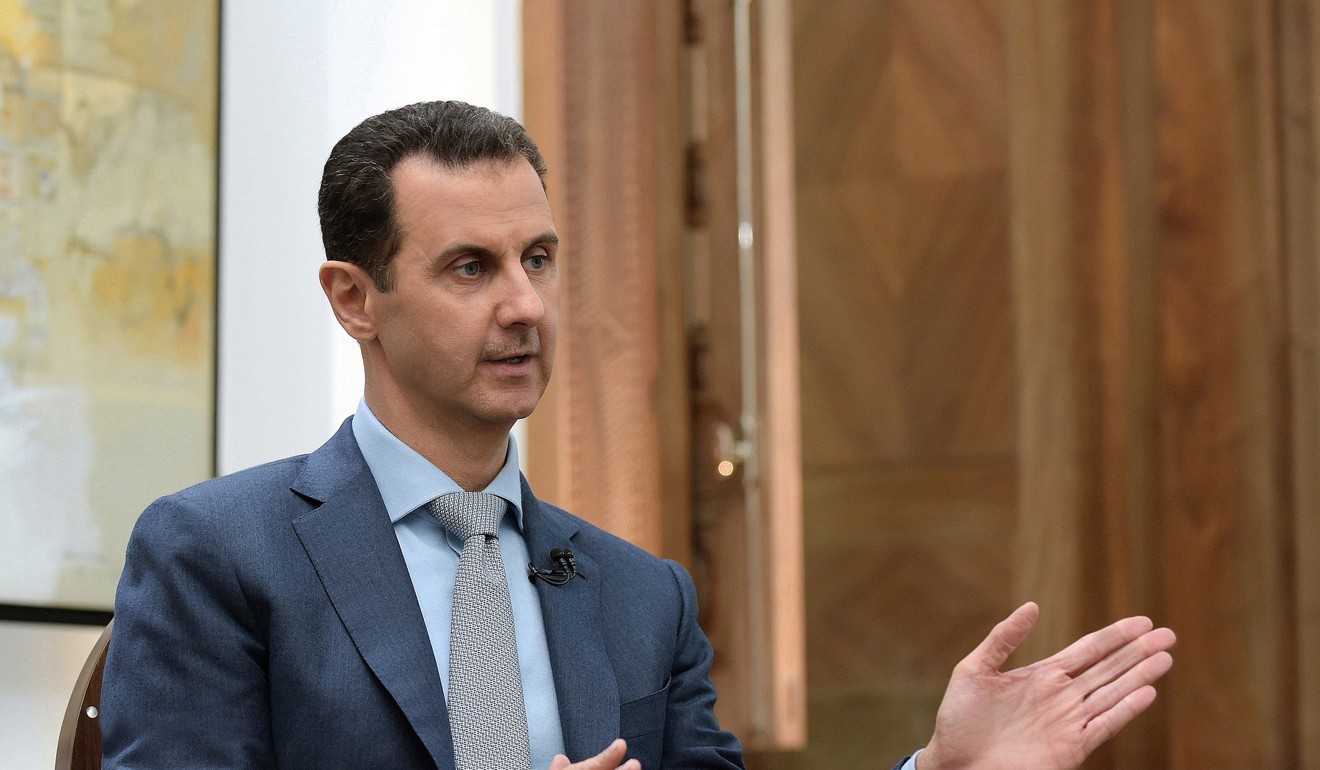

Analysis | Reality dawns in Syria: Bashar al-Assad has won the country’s brutal civil war and his foes have few options left

The key to the Syrian leader’s survival has been his battlefield allies Moscow and Tehran; both have been laser-focused on keeping him in power

In southern Syria’s chilly late winter of 2011, a scrap of schoolboy graffiti reading “Your turn, Doctor” – a mocking call for the overthrow of President Bashar al-Assad – helped spark a ferocious civil war that has left hundreds of thousands dead and millions displaced.

Now, there is a growing diplomatic consensus that Assad, the 51-year-old ophthalmologist who inherited Syria’s leadership 17 years ago from his dictator father, has almost certainly prevailed against efforts to dislodge him militarily – and that his opponents need to come to terms with his political survival as they plot a new course.

The multisided war, midway through a seventh brutal year, is far from over. But Assad’s consolidation of control in key parts of the country, and continued crucial aid from allies Russia and Iran, have contrived to make it virtually impossible for the rebels who once enjoyed US support to drive him from power, long-time observers of the conflict claim.

Bashar al-Assad’s government has won the war militarily. And I can’t see any prospect of the Syrian opposition being able to compel him to make dramatic concessions

“Bashar al-Assad’s government has won the war militarily,” said Robert Ford, a former US ambassador to Damascus who witnessed the uprising’s earliest days. “And I can’t see any prospect of the Syrian opposition being able to compel him to make dramatic concessions in a peace negotiation.”

The government has yet to fully secure areas around the capital, and fighting continues in various pockets of Syria’s east as well as the northwestern province of Idlib. Yet even Assad’s staunchest international adversaries see the continuation of his rule as a fait accompli and have urged the rebels arrayed against him to do the same.

“The nations who supported us the most ... they’re all shifting their position,” said Osama Abu Zaid, an opposition spokesman contacted by phone. “We’re being pressured from all sides to draw up a more realistic vision, to accept Assad staying.”

The key to the Syrian leader’s survival has been his battlefield allies Moscow and Tehran; both have been laser-focused on keeping him in power.

Russia dispatched warplanes and elite Spetsnaz units in 2015 to stop the opposition’s advance, just as a coalition of hardline Islamist rebels was on the cusp of overrunning key government bastions. Iran poured in materiel as well as manpower, including proxies from as far afield as Afghanistan, to bolster Assad’s exhausted troops.

Diplomatically, Russia has repeatedly wielded its veto power on the UN Security Council to shield Damascus from punishment, and has worked to forge de-confliction zones that have given the army the breathing space it needs to mount offensives in the eastern province of Deir-ez-Zor.

Meanwhile, the opposition has found itself with international backers bereft of the political will to remove Assad, with each government pursuing its own strategic priorities in Syria.

Turkey, long the primary conduit for the opposition – its border towns became rearguard rebel bases early in the crisis – is now fixated on stopping the advance of the People’s Protection Units, or YPG, a Syrian Kurdish faction that has been one of the most effective fighting forces against Assad. Ankara views it as a proxy for a domestic Kurdish separatist group it has fought for decades.

That has put Turkey on a collision course with the US, which has built up the YPG as the nucleus of an anti-Islamic State (IS) force that it also hopes will block Iranian aspirations in the country.

The opposition’s Persian Gulf patrons are also at one another’s throats, with Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates squabbling with Qatar even as they face a quagmire in Yemen, where a 29-month Saudi-led air campaign has led to more than 10,000 deaths and sparked an epic humanitarian crisis, including one of the world’s worst cholera epidemics.

Meanwhile, Assad’s government is signalling its confidence in ways large and small. Last month, the Damascus International Fair – once a showpiece of economic and technological prowess, attracting investors from across the Arab world and beyond – was held for the first time since being shuttered early in the war.

“The fair is the gateway for the declaration of victory in Syria,” its director, Fares Kartali, said by telephone from Damascus.

Meanwhile, those who had hoped to drive out Assad see a bleak realpolitik playing out among countries that the opposition counted as backers. Abu Zaid, the opposition spokesman, said France and other European powers are more interested in stanching the flow of Syrian refugees and stabilising the country enough to send many of those already in Europe back.

He and other opposition figures chastised the Obama and Trump administrations, saying the US had all but abdicated the wider battle to Russia while it focused on countering IS and al-Qaeda. Although President Donald Trump ordered an air strike on Syria after its forces were reported to have carried out a chemical weapons attack in April, he also has steered clear of calls for Assad’s removal.

Other than a desire to combat jihadist groups, “it’s as if the US doesn’t care,” said Abu Zaid.

Yet the opposition itself has often been its own worst enemy. Plagued by internal divisions, with different factions beholden to often competing interests, it was only able to mount a serious challenge to government forces when self-styled “moderate” forces were allied with Islamist groups, including al-Qaeda’s one-time affiliate, the Nusra Front.

Not only were those groups anathema to the West, they were excluded or refused to take part in the tortuous UN-brokered negotiations between the government and the opposition in Geneva and Kazakhstan’s capital, Astana. That has meant that most of the groups taking part in the diplomatic process have very little actual power on the battlefield.

Damascus, meanwhile, has achieved battlefield gains that have cemented Assad’s grip over what policymakers like to call “useful Syria”. Damascus, Aleppo, Homs and the coastal Mediterranean cities of Tartus and Latakia are firmly in Assad’s hands. His forces’ march to the east has brought desperately needed energy supplies back under government control.

All these factors have led to a wide-scale campaign to “recycle the regime,” said Yahya Aridi, an opposition spokesman and member of the Saudi-backed High Negotiations Committee, the rebels’ top representative body.

In the longer term, those who bet on Assad’s defeat will now probably find themselves shut out of a lucrative rebuilding effort – part of a larger geopolitical pivot on the part of Syria’s leadership.

Iran, Russia and China are well-positioned to reap the bonanza of a reconstruction projected by the World Bank to cost US$226 billion.

Assad, in a speech last month, described a policy of turning “toward the East”.

With more UN-mediated talks on tap in Geneva, the opposition, though publicly holding fast to its demand for Assad’s departure, is being steadily prodded toward a new vision – not only by external forces, but by a desperately war-weary nation.

“There do not appear, at this stage, any realistic options for Assad’s departure, absent a dramatic escalation of the conflict, or a lucky shot,” said Andrew Parasiliti of the Centre for Global Risk and Security at RAND Corp. “Many Syrians also just want to get on with their lives.”